It was whilst I was cycling home from the studio this morning that the idea first came to me. I was thinking about the two paintings on which I am currently working, both of which are based on the landscape around Hafodyrynys, Wales (the village in which my Grandmother grew up) and one of which I intend to show, veiled, at the Mine the Mountain exhibition in October.

The paintings themselves were going quite well, but remembering the original idea behind them, I realised that there was something missing. The original idea was that these paintings, or rather the final selected painting would be based on both the death of my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers who was killed in action in the Second Battle of Ypres on May 8th 1915 and my birthday, May 8th 1971. The title of the piece was provisionally May 8th, but as is often the case, the painting has led me away from this. That isn’t to say the subject has been lost completely; I still want to think about Jonah, but how do I show him in the painting? How do I show the ambiguity between existence and nonexistence/death?

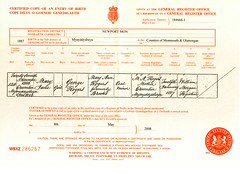

The answer came as I thought about names and some of the documents I have obtained through researching my family tree. Almost without exception, none of my ancestors from Wales at this time could read or write and all of them signed their name (or rather, indicated their presence) with an ‘x’. The ‘x’ therefore becomes a sign of a presence, but one which is anonymous.

Of course the ‘x’ is usually accompanied by the line; ‘the mark of…’ (as above) but without that, the human becomes relegated to this nondescript, anonymous sign (one could argue of course that we are all, in our names, reduced to signs, but the ability to write allows us to transfer to the page – and therefore leave to posterity – much more than just the name by which we are known). The act of making that mark instead of writing one’s name is also very significant. It levels all those who make it; it renders everyone the same – at least in the eyes of history. One could say that the greatest leveller of all is death and that the ‘x’ becomes the mark of death; presence is defined by absence.

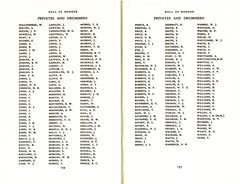

We know much of what happened in the past through the written word although there are of course many other sources in which it’s also revealed; paintings, artworks, newspaper stories, oral histories/stories, fingerprints, photographs and so on, but for the most part, we know about the past through what we read. I have written about the limits of the written word before in relation to the work I did on ‘The Gate’, but looking at it again in relation to these paintings and to my previous work/research, there is something very poignant about these anonymous signatures; I can’t help but think of the names we see on memorials, carved into walls and so on. Imagine if they simply read ‘x’… For many who died in the Great War and whose bodies were either never found, names have been lost and an ‘x’ is perhaps all one could write on their behalf.

In relation to the landscape, ‘x’ has different connotations; on maps it marks a spot – it denotes the presence of something, a thing which is present and yet absent – hidden away from sight and mind like buried treasure. Marking the canvas with an ‘x’ would give the painting the meaning I was looking for; the presence of someone absent; the reduction of everyone in time to complete obscurity. Furthermore, taking what I wrote in the paragraph above, ‘x’ marks the last resting place of all those (including my great-great-uncle) whose bodies were never found.

The paintings are still in the early stages but there was instantly something about the marks which appealed. In some respects I saw them (those in the sky) as angels which given the nature of the work seemed relevant. They also reminded me of the stars one sometimes finds painted on the ceilings of cathedrals or in mediaeval manuscripts. But those ‘on the ground’ called to mind something else, something which given Jonah Rogers’ fate gave the paintings another dimension; first the shape reminded me of the deckchairs I made for the Residue exhibition (The Smell of an English Summer 1916 (Fresh Cut Grass))..

…and secondly, the x-shape defences one sees on wartime photographs such as those of the Normandy landings below…