I’m currently reading an excellent book by Colin Renfrew, Senior Fellow of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, entitled ‘Figuring it Out’, in which the author examines what he describes as ‘the parallel visions of artists and archaeologists,’ with an emphasis on contemporary art practice. As an artist with a deep interest in archaeology, I had to buy the book, and I’m very glad I did, for it’s helped me pull together numerous strands of thinking which have emerged from my research over the course of the last four years; in particular, the idea of the physical or ‘sensed’ present as a lens through which to ‘see’ the past. Professor Renfrew writes: “The past reality too was made up of a complex of experiences and feelings, and it also was experienced by human beings similar in some ways to ourselves.” The way we experience the present then, tells us a great deal about how people experienced the past when it too was the present.

I’ve written before how one of the problems we have in considering past events is the temporal distance which separates us. Reading a history book, although we know its content is‘ factual’, is nonetheless an interpretation of events; an outline at best no matter how well researched and well written it is. There may be a structure, just as in a novel, with a beginning, a middle and an end. But of course reality isn’t really like that – the boundaries are much more fluid. Necessarily therefore, a history of any event will be full of holes and it’s these holes which interest me.

In October 2006, I stood on the Ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau and my experience there is something with which I’ve been working ever since, even whilst researching different places – whether other camps such as Bełżec or the battlefields of World War One – it’s that particular moment which I have been researching, peeling back the layers comprising the moment, much as an archaeologist digs through layers of stratified soil to uncover a whole range of times.

History is, in some respects, like fiction. What is known and written about can only be surmised from surviving evidence and what we ‘see’ as receivers of that knowledge, can only be imagined. What’s always missing is a sense of the present, as if what happened in the past always followed a script, one in which the main protagonists took their cues and delivered their lines accordingly. Hindsight, which one can hardly escape, joins all the dots, but leaves many gaps between the lines.

In the foreword to Peter Weiss’ book The Aesthetics of Resistance, Frederic Jameson writes how for the critic Georges Lukács, the world historical individual should never be the novel’s main protagonist, but rather seen from afar by the average or mediocre witness. We could say the same for history; that events described in history books are ‘best’ when seen through the eyes of those ‘average’ or ‘mediocre’ witnesses; people which history labels as ‘the mob’ or the ‘masses’; who are often buried beneath unimaginable numbers – mass graves within which, their names and individual identities are forgotten.

I’ve produced numerous works which examine this idea of the anonymous individual in history, but there’s another element I try to show, and that’s the ‘everydayness’ of any historic event. This is, I believe, key to our understanding of the past, for not only is history best seen by the ‘average’ or ‘mediocre’ witness, but – for me at least – when the main event is glimpsed as a backdrop to an individual’s own life experience. That’s not to say the event should always be viewed through the eyes of someone far away from the scene, but that it should always be seen behind the individual, rather than the individual being buried somewhere beneath.

In the time after my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau, I wanted to find a way of identifying with those who died there. That’s not to say that I can identify with what they went through, no-one who wasn’t there can ever claim to understand what it was like to suffer, but we can seek to separate the individual from the grim statistics and site the camp in the landscape of the everyday world. Again, that’s not to say that Auschwitz-Birkenau was an everyday place, but what’s important for me, in understanding the past, in filling in the gaps which history inevitably leaves behind, is an understanding that the everyday world was happening at the time. Whatever event in whatever period we’re researching, the world was happening around it. The wind blew in the trees; the birds sang and the rain fell. The sun rose in the morning; the sky was just as blue or grey as it is today. There were clouds with their shadows, and during the night, the moon might be reflected in small pools of water, like that described by Auschwitz survivor, Filip Muller – in a pit soon to be filled with bodies. The events like the place were not everyday, but they took place regardless in an everyday world and understanding this ‘everydayness’ can help us understand and picture much more clearly events of the past.

For example, we can read hundreds of titles about the Holocaust and World War One, but when we read in the Diary of Adam Czerniakow – the ‘mayor’ of the Warsaw Ghetto – what the weather was like on a particular day, suddenly, in words like ‘beautiful weather,’ the full horror of the Holocaust is revealed, because, with these words at least, we can identify and – albeit in a very small way – empathise with someone who suffered; the past in effect becomes very much present.

In Birkenau, it wasn’t so much the sight of the gas chambers which was so horrific, or even the gaze of the infamous gatetower, but rather the way the trees moved, just as they’ve always moved, right throughout history.

Similarly, on the battlefields of the Somme, just as we cannot comprehend the horrors faced by the soldiers – the incessant shelling and machine gun fire – we can nonetheless see and feel the ground beneath our feet; we can see the sun in the sky, and feel the wind on our faces, and it’s these everyday details which take us, albeit just a little, into the midst of a battle. Of course we still need history to draw in the outlines, but it’s these other details which prevent history being a script. Events in history were not preordained, people made choices and choices can only be made and acted upon in a moment – in the present. Understanding the present therefore – that space wherein reside all our hopes and fears, our dreams and ambitions, and into which we bring our memories – is key to our understanding of the past.

In a passage written by Tadeusz Borowski, another Auschwitz survivor, we read the following: “do you really think,” he asks, that without hope such a world is possible, that the rights of man will be restored again, we could stand the concentration camp even for a day? It is that very hope that makes people go without a murmur to the gas chambers, keeps them from risking a revolt, paralyses them into numb inactivity.” People often ask why, when faced with certain death people didn’t revolt or even attempt to escape? If we read history as a script we might well feel obliged to ask that question, but when one’s alive in a moment, that in which we continue to exist, we will do anything to maintain that existence, and second by second that was achieved by doing nothing, right up to the end, for up to the end there was always the hope that something would change. Again, it’s through understanding what it means to live in the present that we can understand the past a little better.

In his book ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology,’ Christopher Tilley writes: ‘The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would be impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects. Dillon comments: “The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”’ Just as the trees function as Other therefore, so must the sun, the stars, the clouds, hills, mountains, the sea, rivers, the wind, the rain and so on. Objects too, excavated during digs or on display in museums, act in much the same way.

Through archaeology, we excavate moments. We might come to better understand epochs and eras, but revealing a stone beneath a field which once belonged to part of a road reveals the movement of individuals and thereby an individual. And as we in the present stand on that stone and sense the world around us, we can bridge the gap between the past and present, even if that gap is one, two or three thousands years. If we walk along the line of the road, what we know of any relevant history becomes animated. With the aid of the ‘everydayness’ of the world we can position ourselves within an event – even if that event took place many miles away. We can become the ‘average’ or ‘mediocre’ witness, and rather than seeing a past event as one sandwiched between two pasts (those more and those less distant) we can instead bring to that past, the concept of the present and consequently the unknown future.

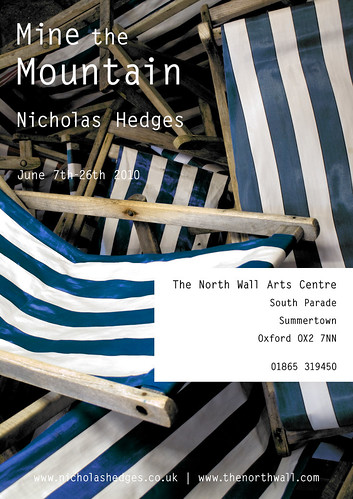

At the beginning of his book, ‘Figuring it Out’, Professor Renfrew looks at Paul Gauguin’s painting ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going to?’ (1897) a title, and a question, which many artists and archaeologists alike have tried to answer. The questions posed in the title of are of course about the past, the present and the future and in reading this book I could see how these questions have always been there behind my work. After visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau and in an attempt to find anonymous individuals in history to whom I was related I began to investigate my own family tree, and, over the course of the last few years I’ve found several hundred ancestors going back on some lines as far as 1550. A year before she died, my grandmother told me about her childhood in Wales and in particular about my great grandfather who died in 1929 after years working in the mines. The following is an extract from that conversation:

‘I can see him now because he went up our garden over the road and the mountain started from there up… and he’d go so far up and he’d turn back and wave to us, and if we went out to play, our Mam would say, ‘you can go up the mountain to play…’ but every now and then our Mam would come out in the garden and we had to wave to her to know that we were alright you know… always remember going up the mountain…’

On visiting Hafodyrynys, the small town where my grandmother grew up, I walked up the ‘mountain’ she’d described and followed the path my great grandfather would have taken to work in the mines at Llanhilleth. On top of the hill I stood and looked at the view. One hundred years ago, when I did not exist, he would have seen the very same thing. One hundred years later, long after his death, I found myself – through being in that place – identifying with him, not because I know what it was like to work in the mines (of course I don’t), but because I saw the same horizon, felt the same wind, saw the same sun and so on. I’d found him there on the path (one which would in time lead to my being born).

I realised too in Hafodyrynys, that I’m not only who I am because of the genes passed down by my ancestors, but because of the things they did throughout their lives, not least because of the roads and paths they travelled, such as that upon the ‘mountain’. Anything different, no matter how seemingly irrelevant and I would not be here, and in a sense, that which I described earlier in relation to my standing on the Ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the way the trees moved seemed pregnant with the horrors of the Holocaust, is relevant here, albeit for different reasons; the everyday, insignificant details which make up a moment, are key to our existences. Until the time of our conceptions, we were always one step away (many times over) from never existing and again this refers back to what I described at the beginning of this piece; the idea of my own non-existence in relation to past events.

For the catalogue to the third in my series of exhibitions entitled ‘Mine the Mountain’ I wrote the following, in an attempt to summarise my thinking: ‘The Past is Time without a ticking clock. A place where paths and roads are measured in years. The Present is a place where the clock ticks but always only for a second. Where, upon those same paths and roads we continue, for that second, with our existence.’

The last line resonates when considered alongside what I described earlier regarding hope – that emotion which Borowski describes as ‘paralysing’ those who died in the camp.

I wrote earlier too, that through archaeology we excavate moments, that although we might come to better understand epochs and eras, revealing a stone beneath a field which once belonged to part of a road reveals the movement of individuals and thereby an individual, one continuing his or her existence for a second along the way. Artist Bill Viola wrote: ‘We have been living this same moment ever since we were conceived. It is memory, and to some extent sleep, that gives the impression of a life of discrete parts, periods or sections, of certain times or highlights.’ If we take what he says regarding this ‘same moment’ – that which we’ve been living continuously – along with what I’ve written above regarding pathways taken by our ancestors, we can see that that ‘same moment’ extends beyond the limits of our own existence and that moments and epochs are in the end, one and the same thing. The gap between the past and present – however big or small the temporal divide – is removed.

To conclude…

An ancient road, uncovered beneath a field, may be thousands of years old but nonetheless it will have been ‘written’ in terms of moments, where one individual amongst many others has carried his or her existence from one moment to the next. And as we walk ahead towards the future, along the line of the road, carrying our own existence with us; as we feel the ground beneath our feet and watch the wind blowing through the trees. As we listen to the birds and smell the scent of the grass, we’ll find ourselves in empathy with every individual who’s gone that way before us. Somewhere, beyond the horizon, Stonehenge is being built; the Romans have landed in England and the Mary Rose is sinking beneath the waves.