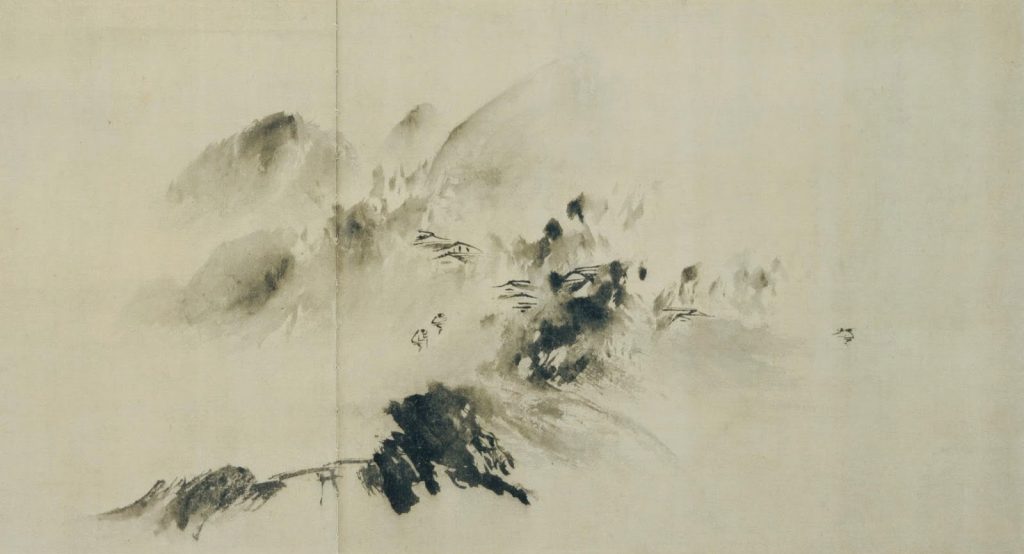

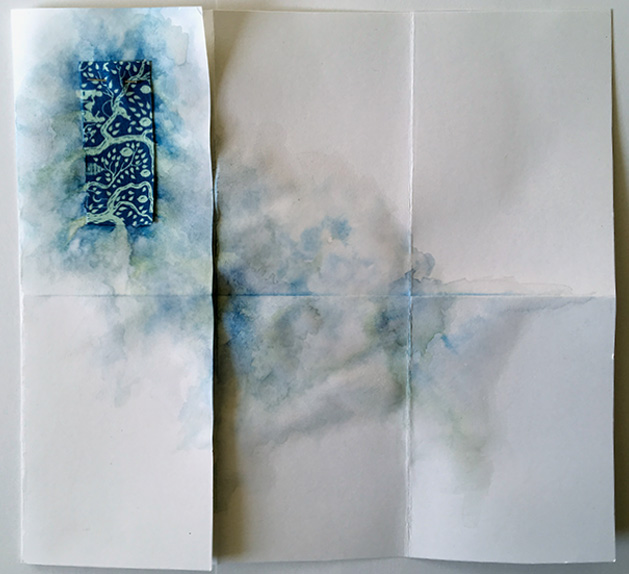

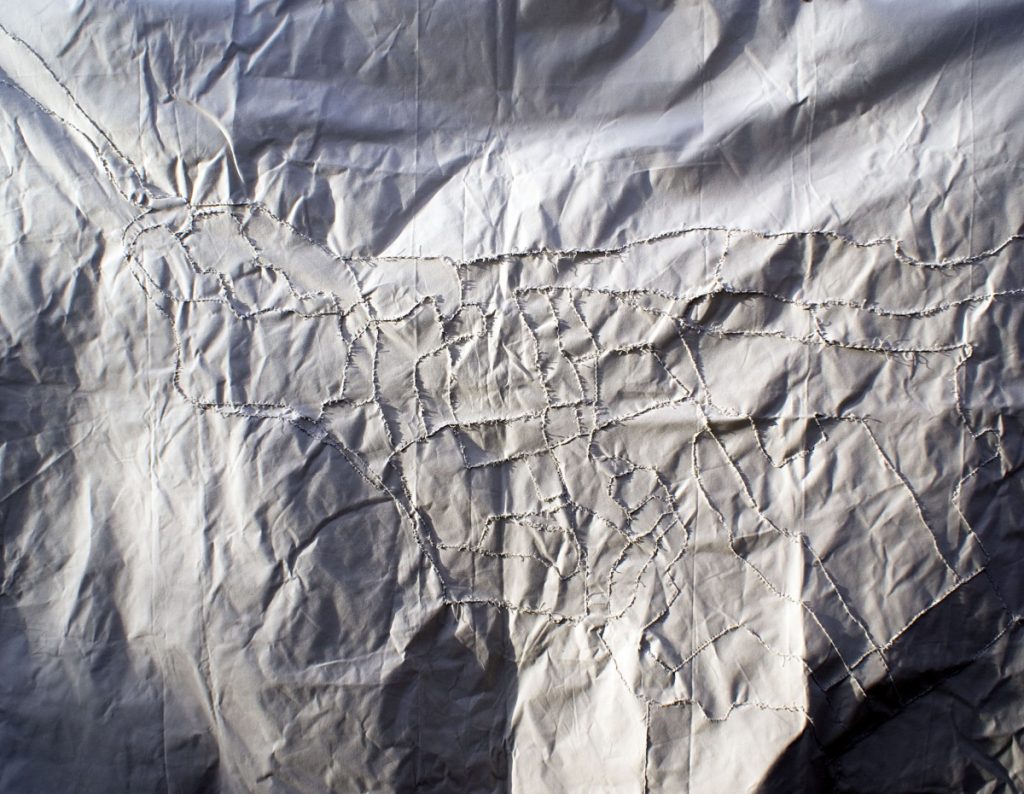

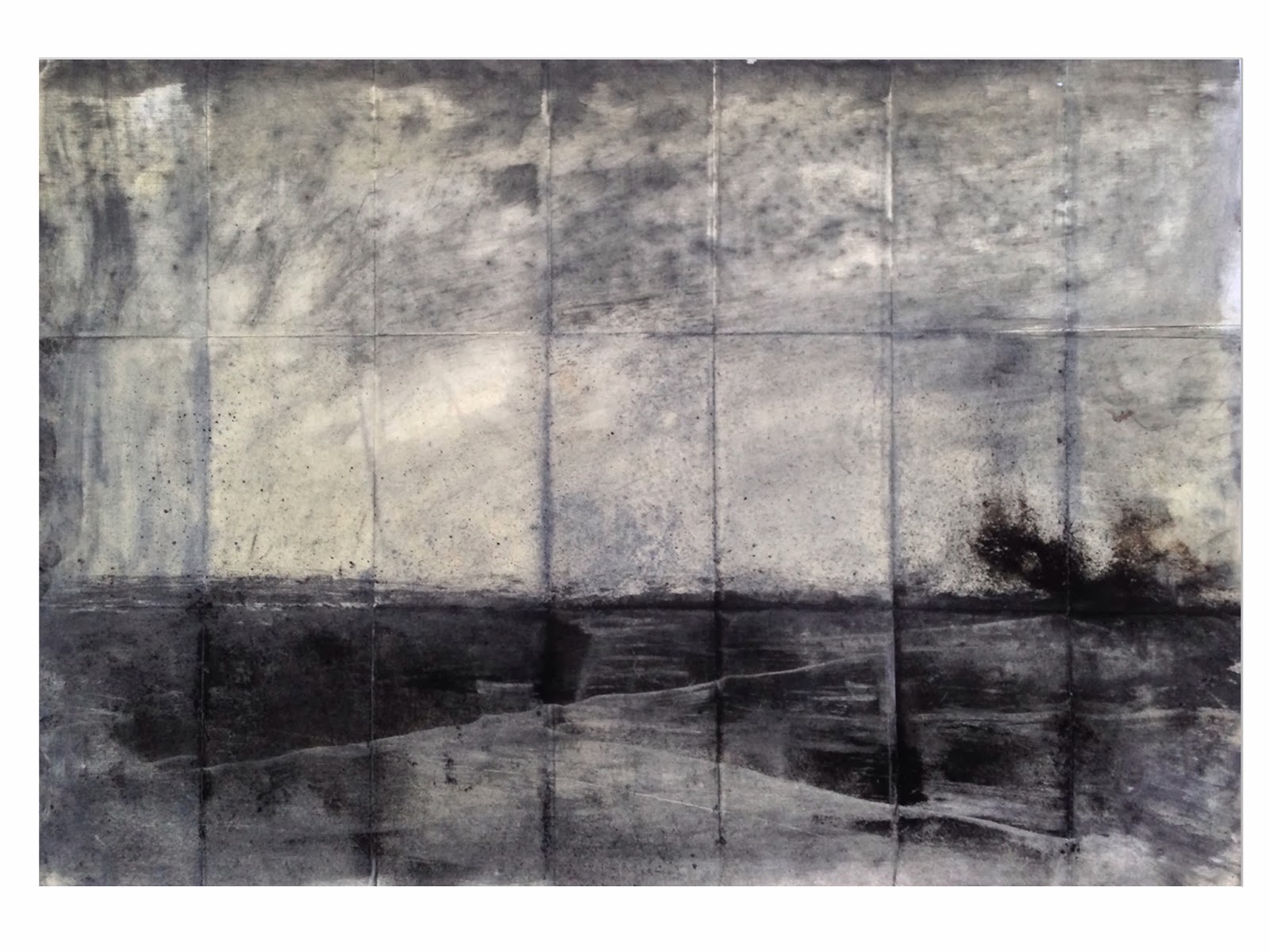

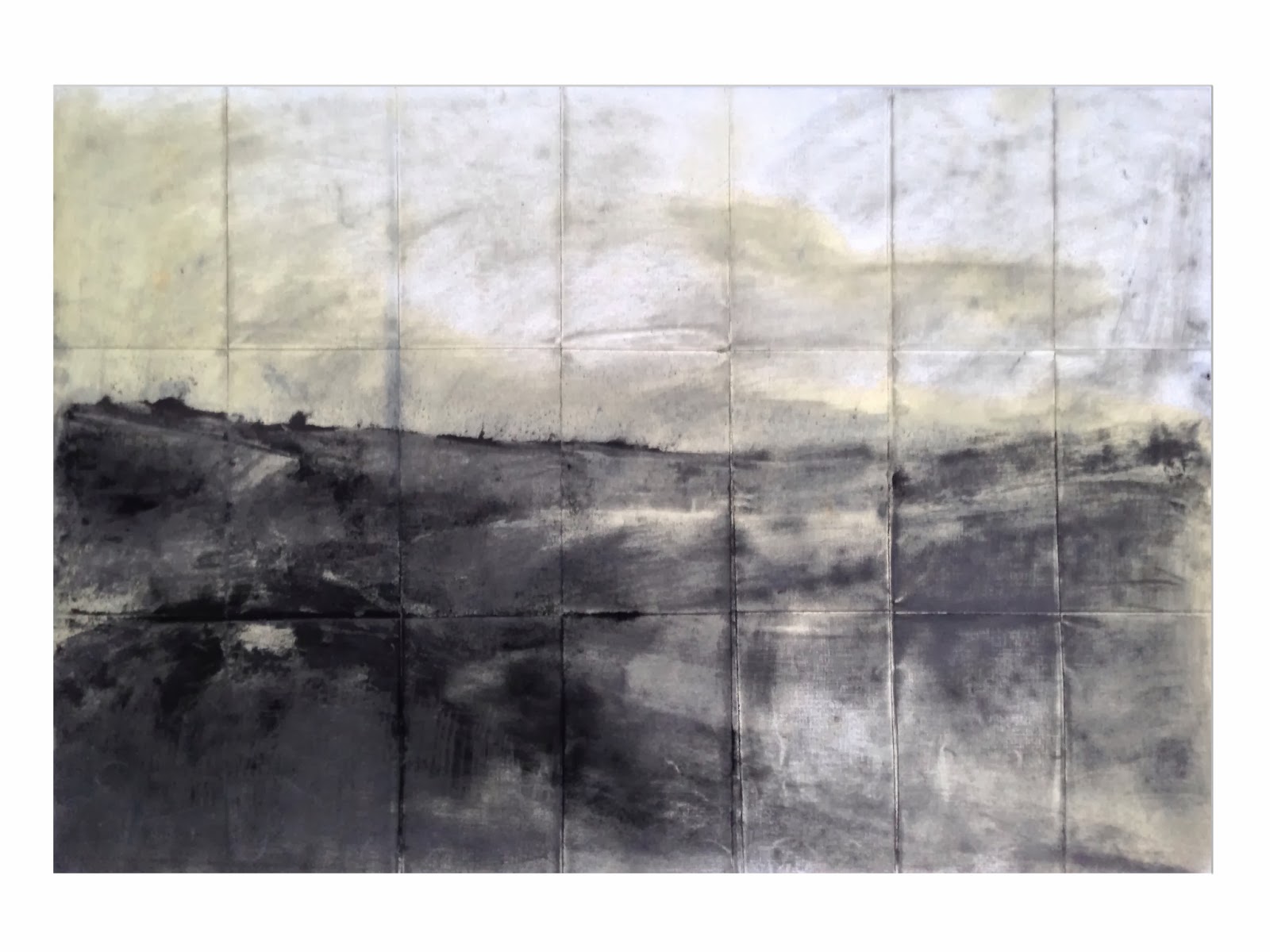

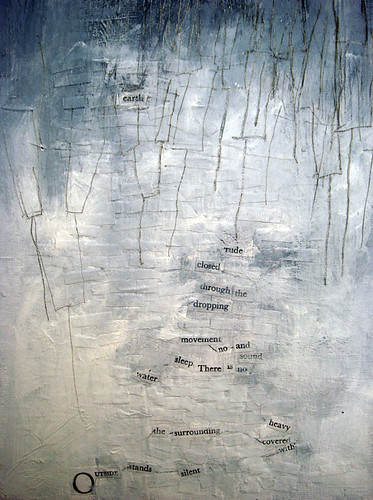

I like it when I make mistakes, or, as in the case of this painting, it wasn’t going the way I thought it would. I’d stuck some inked leaves on the canvas as per a recent painting with the aim of introducing some colour, but having done so, the canvas looked a mess and wasn’t doing what I wanted it to do. So, I took my palette knife and scraped it across the surface of the canvas, removing all the leaves and some of the pain and what was left I really liked.

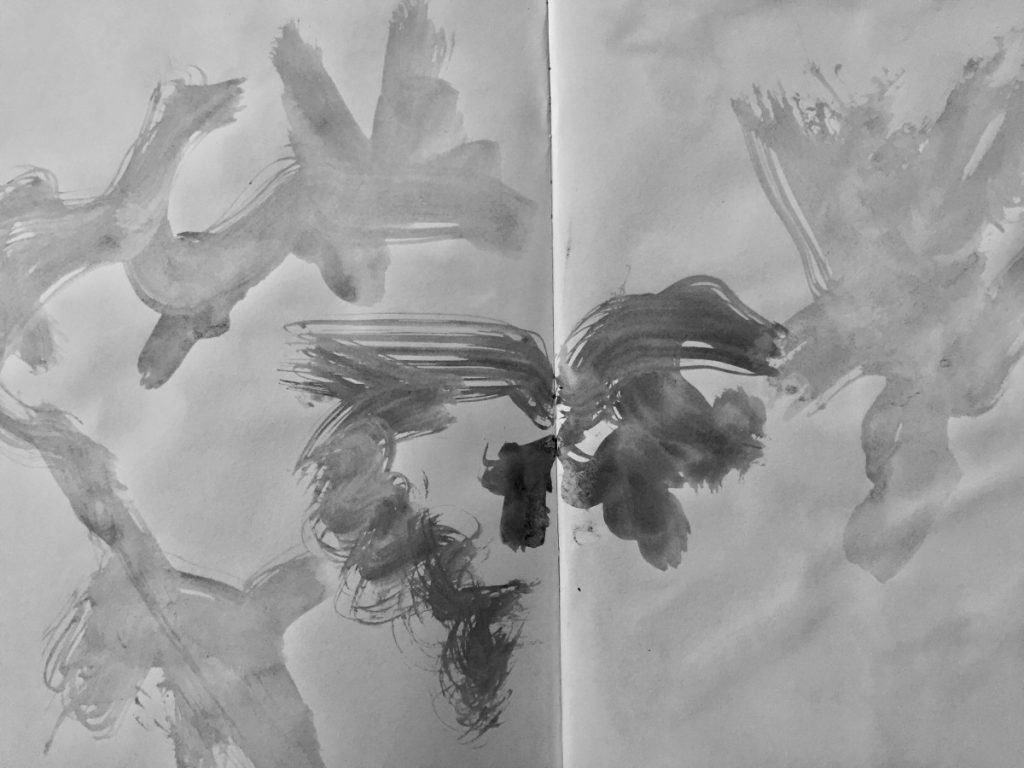

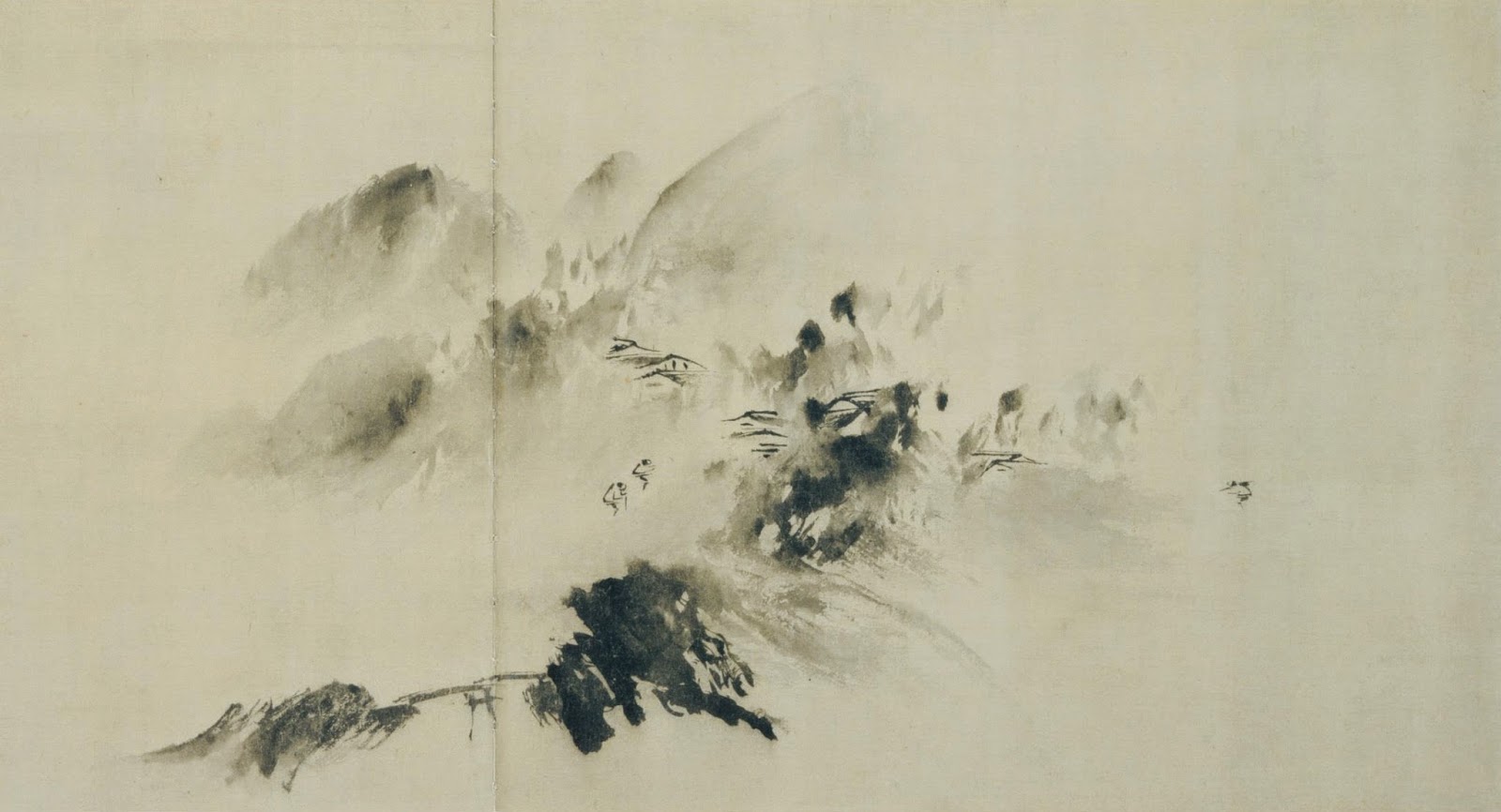

The leaves reminded me of fossilised feathers which is in keeping with the general theme of my work. The colours too reminded me of classical greek ceramics as in the image below.

As with some other recent paintings, I decided to add some flashes of green to the leaves which also worked really well.