I was recently gifted David Whyte’s beautiful book ‘Consolations’ by a friend in which, for the word genius, he writes:

‘Genius is, by its original definition, something we already possess. Genius is best understood in its foundational and ancient sense, describing the specific underlying quality of a given place, as in the Latin genius loci, the spirit of a place; it describes a form of meeting, of air and land and trees, perhaps a hillside, a cliff edge, a flowing stream or a bridge across a river. It is the conversation of elements that makes a place incarnate, fully itself. It is the breeze on our skin, the particular freshness and odours of the water, or of the mountain or the sky in a given, actual geographical realm. You could go to many other places in the world with a cliff edge, a stream, a bridge, but it would not have the particular spirit or characteristic, the ambiance or the climate of this particular meeting place.

By virtue of its latitudes and longitudes, its prevailing winds, the aroma and colour of its vegetation, and the way a certain angle of the sun catches it in the cool early morning, it is a unique confluence, existing nowhere else on earth. If the genius of place is the meeting place of all the elements that make it up, then, in the same way, human genius lies in the geography of the body and its conversation with the world.

The human body constitutes a live geography, as does the spirit and the identity that abides within it.

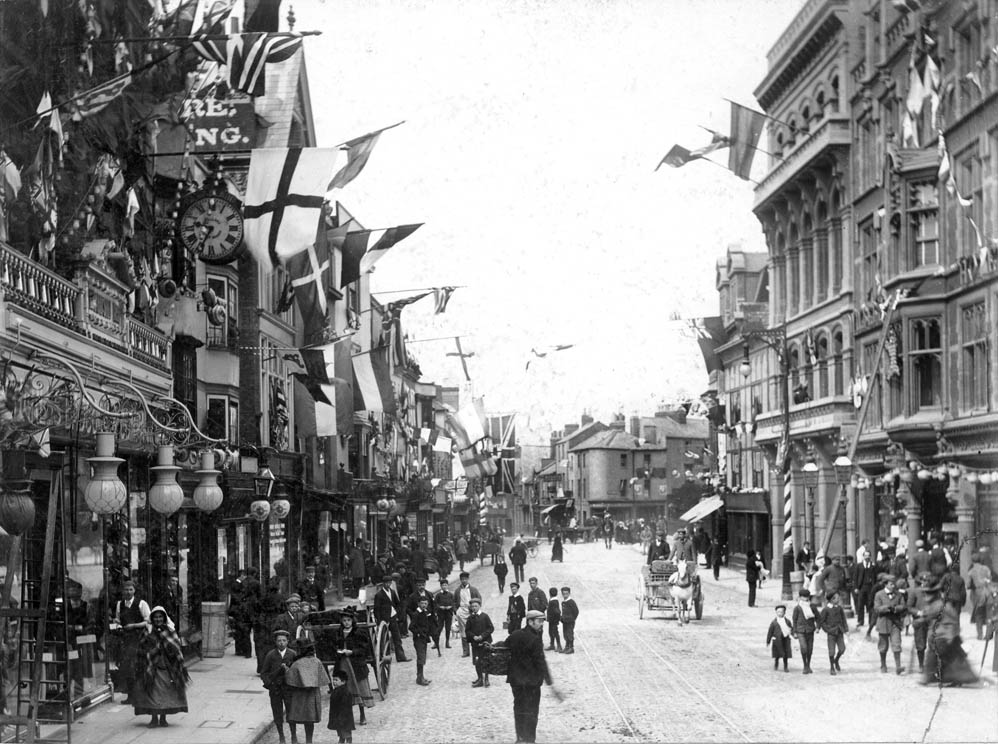

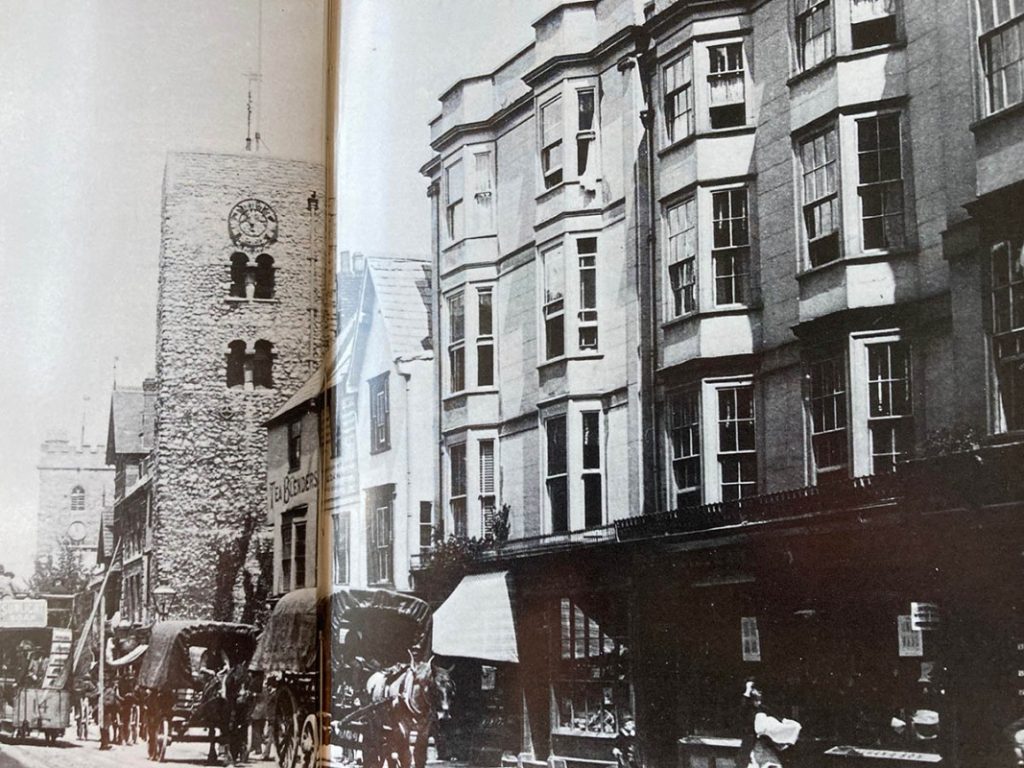

To live one’s genius might be to dwell easily at the crossing point where all the elements of our life and our inheritance join and make a meeting. We might think of ourselves as each like a created geography, a confluence of inherited flows. Each one of us has a unique signature, inherited from our ancestors, our landscape, our language, and alongside it a half-hidden geology of our life as it has been lived: memories, hurts, triumphs and stories that have not yet been fully told. Each one of us is also a changing seasonal weather front, and what blows through us is made up not only of the gifts and heartbreaks of our own growing but also of our ancestors and the stories consciously and unconsciously passed to us about their lives.‘

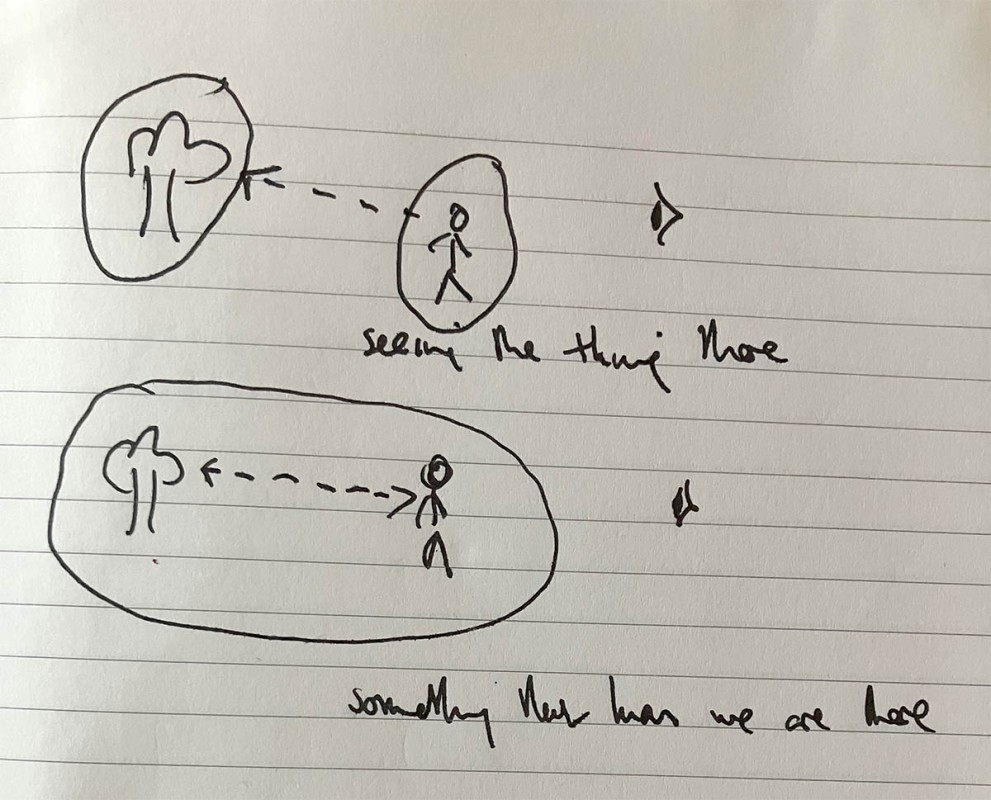

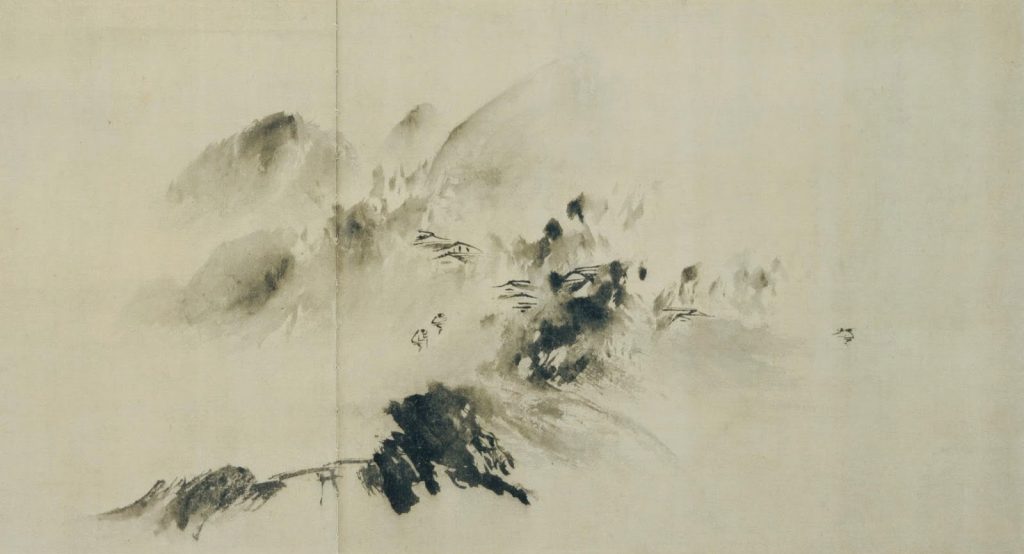

I was really struck by this beautiful passage, not least in relation to my own work and, in particular, the shadow calligraphy I have been painting in woods. In particular, the passage regarding our ancestors really struck a chord. ‘Each one of us has a unique signature, inherited from our ancestors, our landscape, our language, and alongside it a half-hidden geology of our life as it has been lived: memories, hurts, triumphs and stories that have not yet been fully told. Each one of us is also a changing seasonal weather front, and what blows through us is made up not only of the gifts and heartbreaks of our own growing but also of our ancestors and the stories consciously and unconsciously passed to us about their lives.‘

The scrolls I am preparing to make in particular resonate with David Whyte’s words, being as they are pictures from my childhood, including my grandmother’s garden.

The characters of each scroll could be that unique signature, not only of the present moment but also of our ancestors. It combines, which I always love, the idea of now and the past. It is, as David Whyte says, our language; the text of our story and the story of our ancestors too.