1

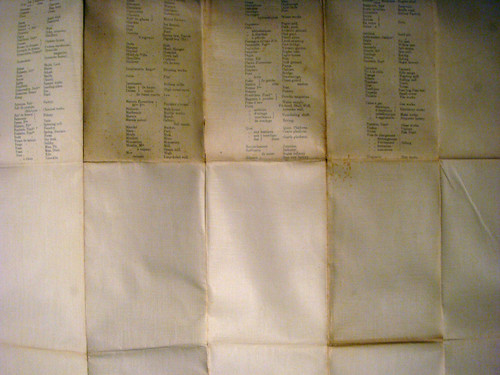

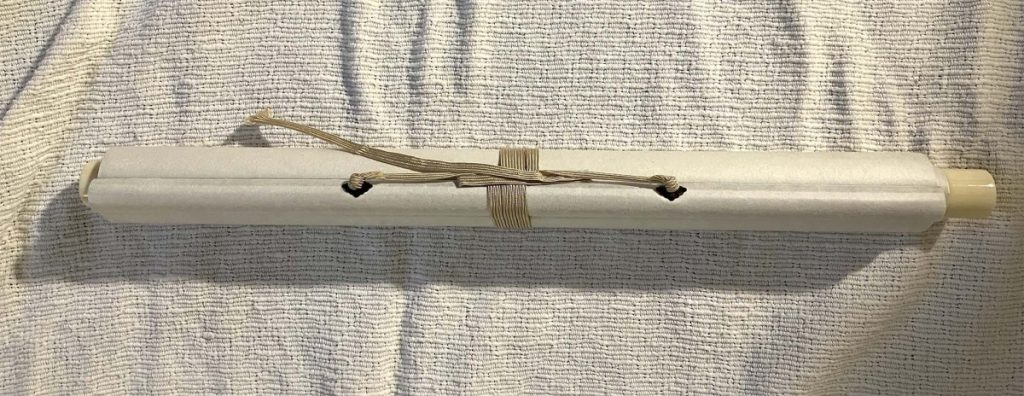

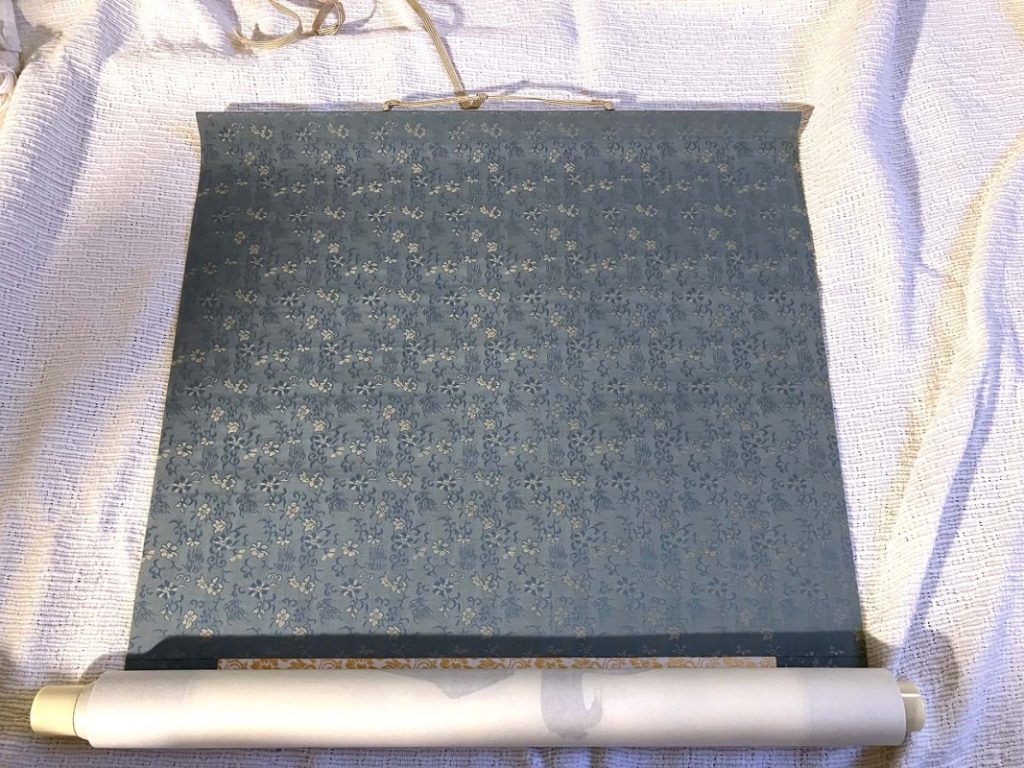

The object is long, perhaps two feet in length. It is off-white in colour and comprises a rod around which a white material is wrapped, bound with a pale gold braid. The object feels nice to hold; it has a nice weight with a texture that is both smooth and rough to the touch. The gold braid is attached to a wooden, half-moon shaped rod of wood around which the top of the scroll is fixed. The braid is wrapped around the circumference of the scroll and as I unwind it, the scroll seems almost to relax. Once unfastened, I begin to unroll the scroll from the top and at once I’m presented with the dark turquoise material patterned with small flowers in gold. It’s a little difficult in the artificial light to be sure of the exact colours. This section of material extends about 18 inches as I continue to unroll it, whereupon it meets another section of material which, centred on the turquoise backing, extends 3/4 of the width of the scroll. It is just over an inch high and again comprises a pattern of flowers, again in gold, but with a cream coloured background.

As I continue to unroll the scroll I see that this small section of material sits at the top of a section of paper on which the characters of the scroll are painted. The first character extends about 12 inches, comprising four distinct sections of brush work. Obviously I can’t read what it says, and as I unroll the scroll down further, smaller characters appear on the left next to a slightly larger one. Underneath these three smaller characters is a red, printed icon. Underneath the larger character beside these three small characters are two more larger ones. As I continue to unroll the scroll, the paper section ends with another small strip of material matching the one at the top but narrower. The dark turquoise material extends beneath this another 10 inches and as I continue to unroll I reach the bottom where the scroll is wrapped around the heavier, ivory coloured rod. There’s a lovely, defined feel to this action, where the end is reached.

Looking at the characters, I can see that they obviously have meaning, that they are painted with an obvious purpose. I can see where the ink is heavier and where it has bled into the paper and also where the brush is dryer. Here I notice the ink is streaked. Even though I cannot read what it says, I can read the gesture of the calligrapher as he or she moves down the paper. As I look at the characters, I can see that along with the gold flowers patterning the dark background there are also flowers in a darker, turquoise colour. The gold of the two strips at the top and the bottom of the paper part of the scroll match the hanging braid at the top of the scroll which in turn picks out the gold flowers of the background giving the whole scroll a sense of unity. Overall the scroll is just over 1m 60cm in length and just over 45cm wide

2

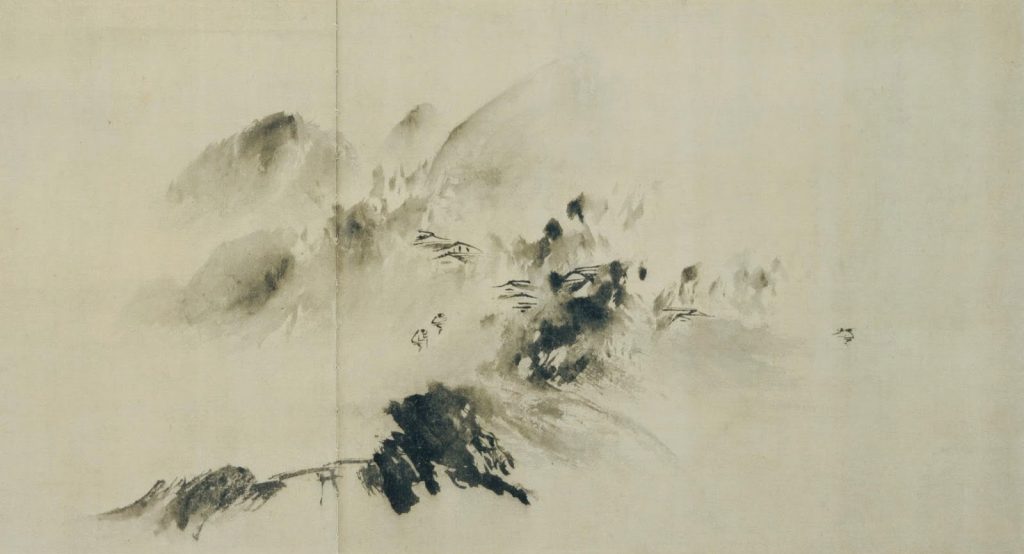

The scroll obviously comprises different parts; the backing material and strips of fabric, the wooden rod at the top, the plastic one at the bottom, the gold braid for tying and hanging and of course the paper section with on which the characters have been written. I can imagine the mind of the calligrapher, how as they wrote these characters, they might have sounded the words in their head. I can almost hear the sound of their thinking along with that of the brush being dipped in the ink and then scraped across the paper. To someone who doesn’t read that language, these words are mute, but because of that I can almost hear their sound in the mind of the calligrapher, perhaps because mine is quiet. I read the scroll by following the gestures. The words become a language of the moment in which they were made.

The sound of the brush on the paper is different where the density of the ink is different. I can almost hear the fullness of the brush touching the surface of the paper and as the ink is released from the brush into the paper and as the brush loses the ink I can hear the sound of the brush change from a slide to scrape, like rolling waves, falling to scrape on the shingle of the beach. I can also read the pauses between the characters where the calligrapher loads the brush once more with ink to make the second character. Here , the sounds of the place in which the words were painted find a way in. Again, there is the same change from the full sound of the loaded brush to the scrape of the ink as it’s lost.

The parts where the brush is dry, where I can hear it scrape across the paper, is where I can see the gesture of the artist most clearly.

Once made the paper would be cut to size and mounted on the material. Was the material chosen specifically for this text? Does it add to the meaning? That I can’t say, but I like the contrast between the precision of the background (the straight edges of the material) and the fluidity of the brush work. Where I can hear the sound of the brush work I can almost hear the sound of the scissors cutting the straight edges of the material, the strips and the paper.

As I roll the scroll back up, it’s as if the scroll is rolling itself, as if it has spoken long enough and needs to rest again. As I roll, I’m aware of the change where the dark material and the text changes to the off-white reverse of the backing material. This plain, off-white material is silent, unlike its interior, where the pattern and the text have spoken. I can just see the text through the material as I roll it, whispering as it’s gradually rolled away.

Did the scroll hang anywhere or was it always rolled up? Was it gift for someone? Did the text have any significant meaning for whoever gave it or received it?

Having rolled the scroll up its full length, it is once more the coiled scroll. I pick it up and I’m aware of the difference between the rolled scroll (quiet, portable, weighted) and the unrolled scroll (which speaks in the sounds both of it making and its meaning) which is light and different to hold.

There are then two very different states of the scroll and as I coil the braid around it, I feel as if I’m in control, whereas when it’s unrolled, I tread around it very carefully. In its unrolled state it is fragile but large, in contrast to its rolled state.

Having rolled the scroll up and tied the braid, it’s as if I am silencing the scroll for a while, knowing that it will speak again. It certainly feels like it has a life of its own and is waiting to be awakened.

3

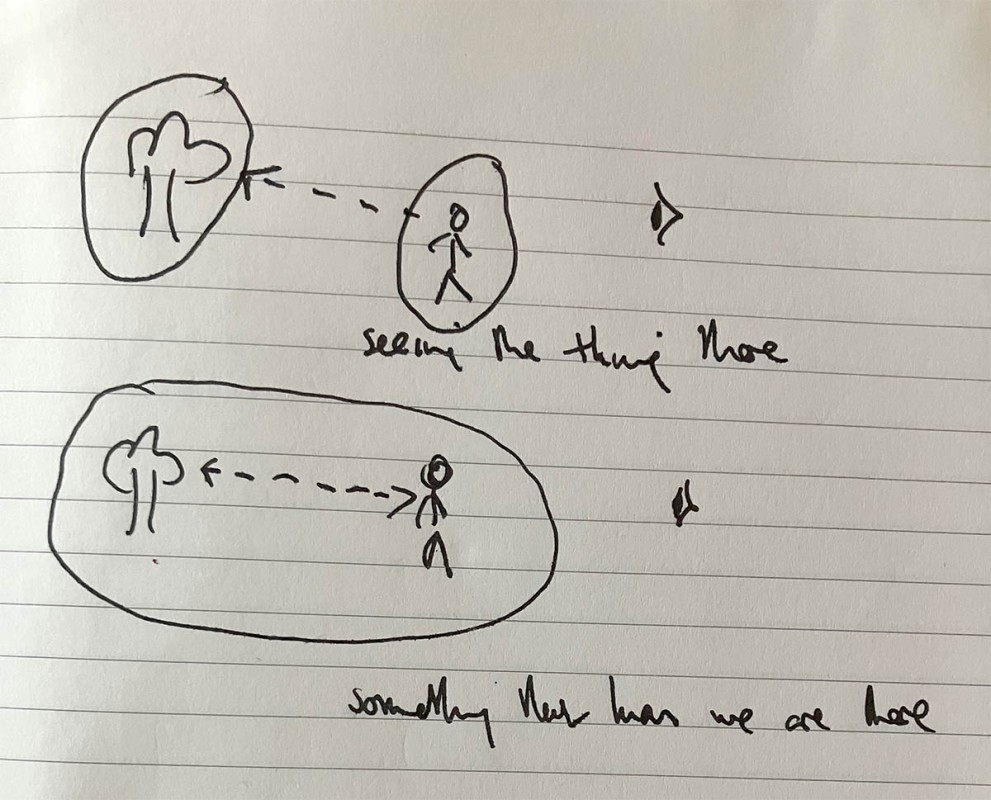

Rolled up it’s silent, but is thinking – it has something to say; it’s as if the actions and the thoughts of the calligrapher are contained within; as if the moment of its making is waiting to be sounded with its unwinding. As I loosen the braids the scroll breathes. There is a sense of ceremony, waiting for that moment to be revealed in this moment, as if the moment contained within will become one with the moment in which we, ourselves, are contained.

As I unroll the scroll, it’s as if the scroll is taking a breath, as if the pattern is an intake of breath ready to speak that which is on the paper.

As I continue to unroll, it begins to speak. The painted brushstrokes are words of a language, not only in the sense of one spoken by a particular group of people, but the language of the moment in which it was made, the ambient sounds, the brush work on the paper.

The backing is the breath.

As it remains in its unrolled state, it breathes. It is a thing all of its own. That moment in time delineated by the sound by the fluid brushstrokes and the precision of the material in which it is framed. As long as it’s open, unrolled, the moment of its making plays in the present.

4

The solidity and tightness of the rolled state – the past hidden.

The untying.

The unrolling and revelation.

The fragility and expanse of the unrolled state – the past revealed.

Then as now.

Delineated.

Breathing.

Defined.

Sounds.

The re-rolling and hiding.

Quiet.

Ceremony and calmness.

Past and present as one.