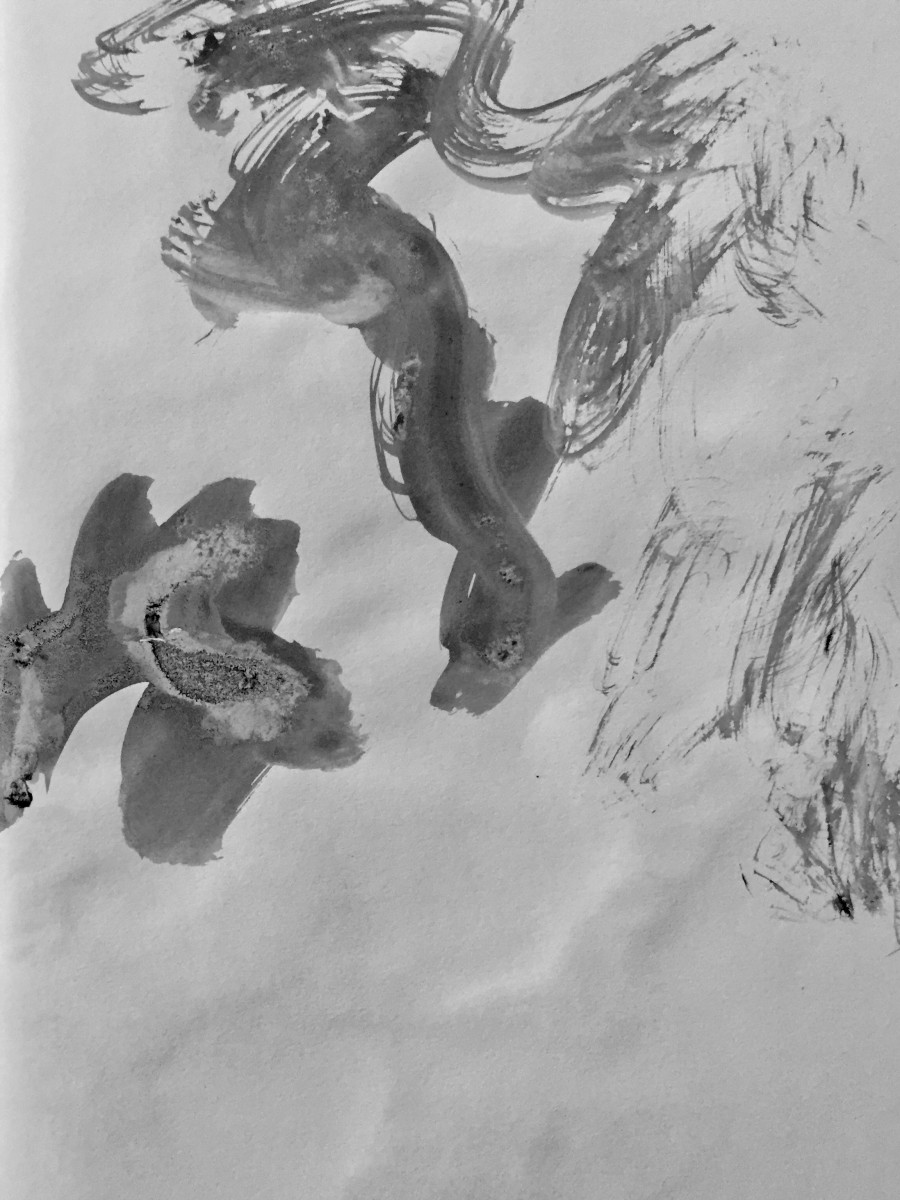

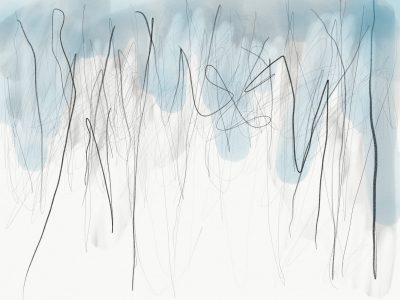

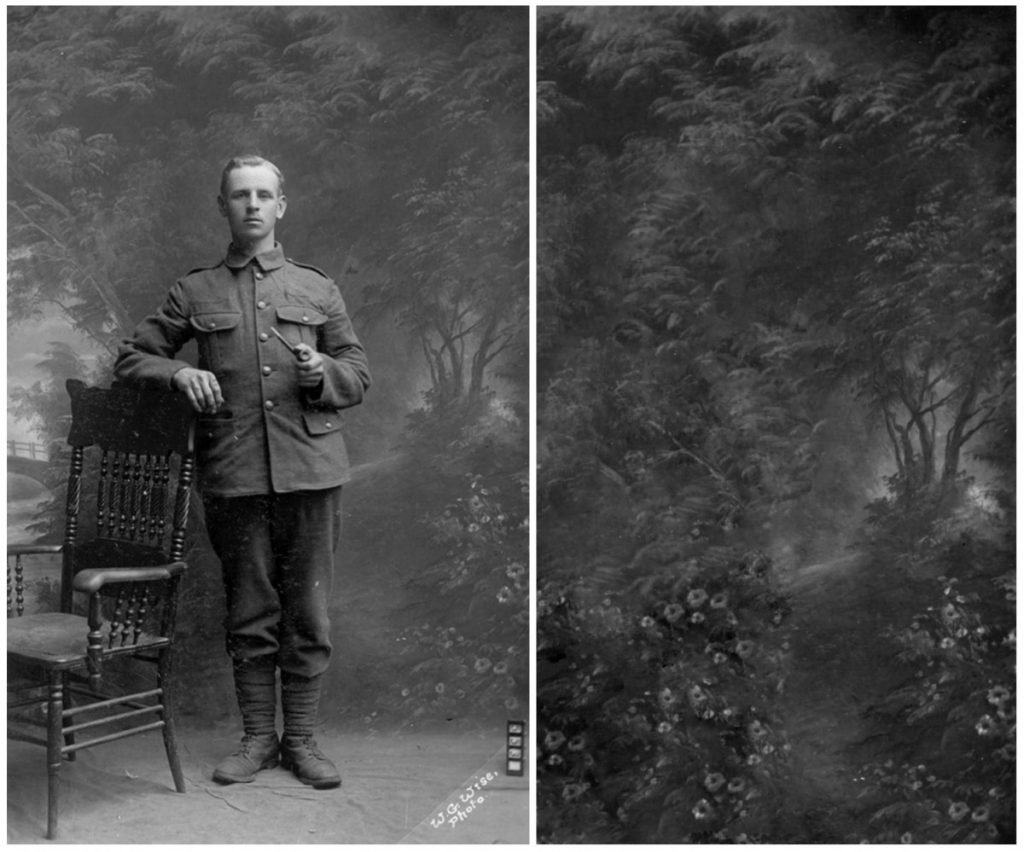

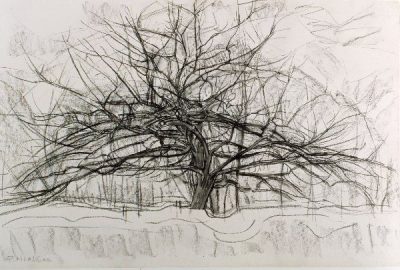

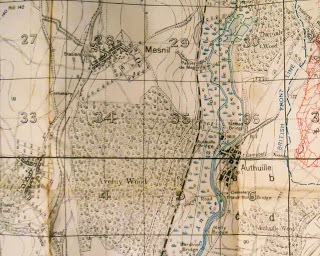

Two years ago I shot some video at Shotover Country Park (see ‘Writing Shadows’) and finally, this weekend, I had the chance to edit the clips together to make a piece entitled ‘The Gone Forest’. The piece is something viewers can dip in and out of rather than sit through from beginning to end, and while it is a finished piece, there are lots of other ways I want to explore using these clips.

For now, here is the video: