This follows on from my last post – Goethean Observation: Pilgrims of the Wild, 1935.

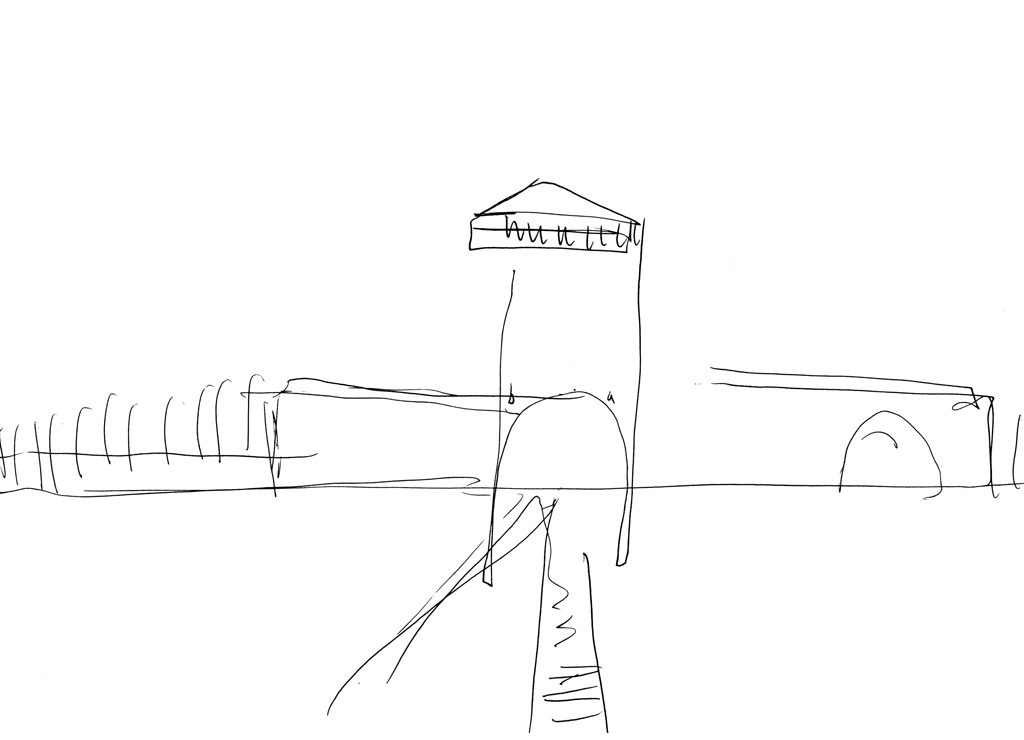

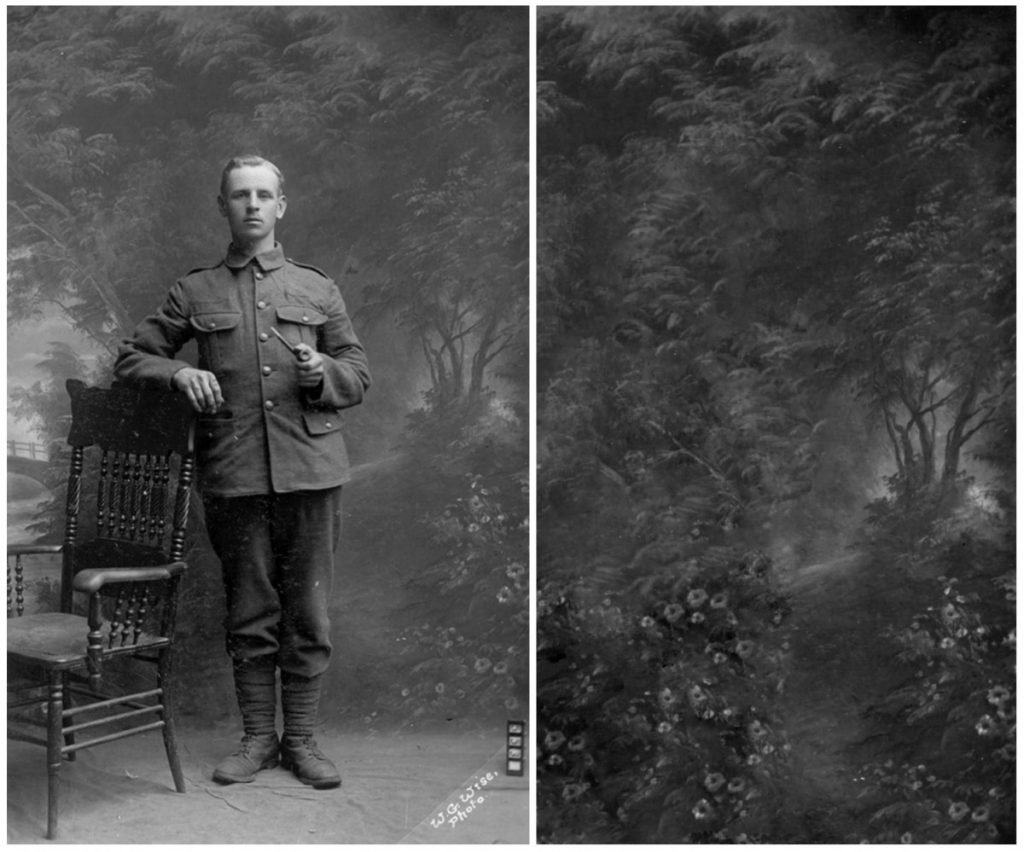

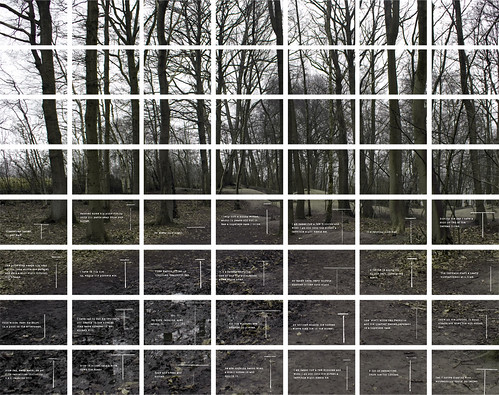

I made this observation after struggling with an idea I’ve had for a long time. The idea came from work I made several years ago on the theme of the Holocaust which led to an installation at Shotover Country park in Oxford (2009) entitled ‘The Woods, Breathing’, pictures from which can be seen here. What I’ve since become interested in is the book that inspired the piece – that which Adam Czerniakow had read on January 19th 1940, remarking in his diary: “…During the night I read a novel, ‘Pilgrims of the Wild’ – Grey Owl… The forest, little wild animals – a veritable Eden.”

I knew there must be a way of using this book, this text, as a means of establishing some kind of empathetic link with Czerniakow. It would be as if by reading the words, I was following Czerniakow through that forest, following the words as if following a trail. The idea of the forest as a means of augmenting empathy was something I’d used in ‘The Woods, Breathing,’ but what of the text itself?

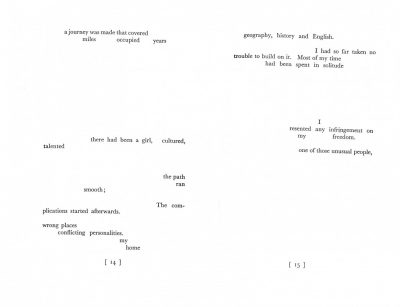

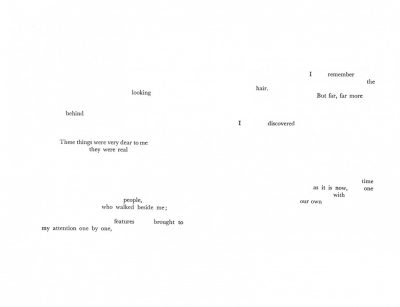

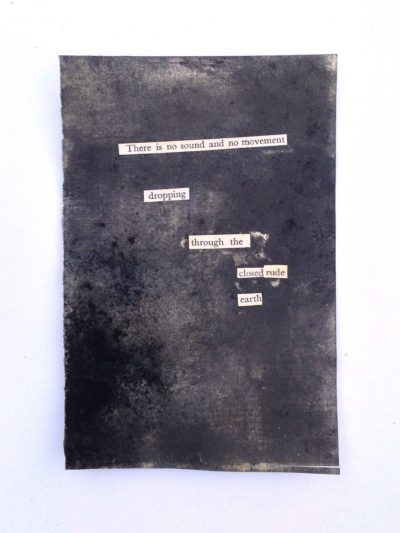

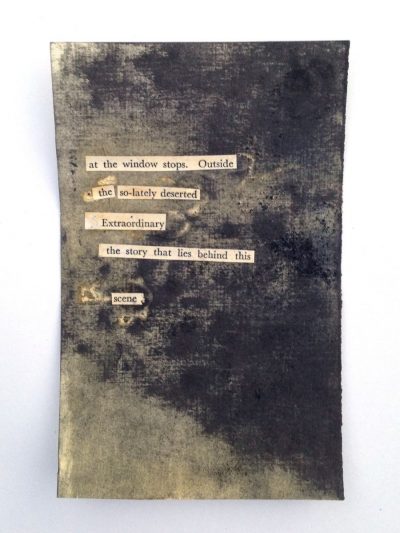

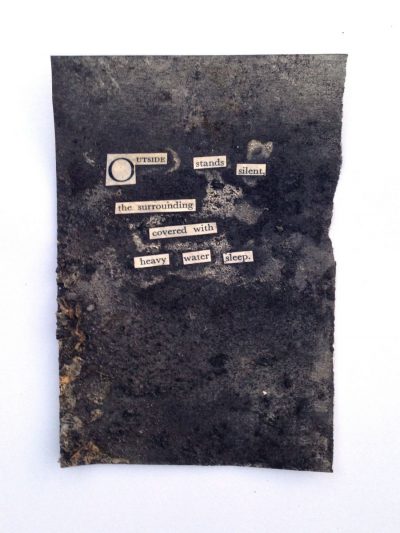

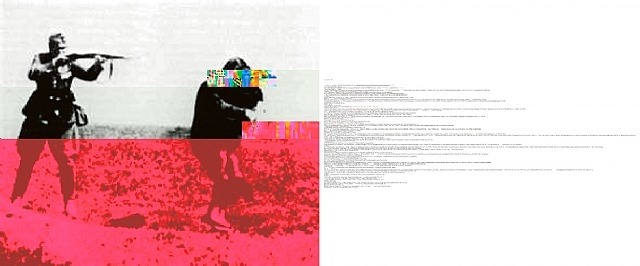

I began by creating ‘blackout poems’ which, although I liked the derived text, didn’t do what I wanted the work to do, that being, to establish some kind of link with the past – with Czerniakow.

I tried incorporating these texts into other works…

…and although I liked the work, they didn’t serve the purpose.

I realised I was, to some degree, putting the cart before the horse. I was falling into bad habits – thinking about the form of the piece much too soon. What I needed was go back to what I had learned during my MA and research the idea properly; that meant starting with looking at the book which I did through a Goethean Observation of Grey Owl’s ‘Pilgrims of the Wild’.

I’d always thought of the text when thinking about this piece, but in doing the observation, that completely changed. As is often the case with these observations, a few words from the thousand or so written stood out:

I’m aware of the book’s weight.

There is an exchange of sorts.

When the inscription was made it became something else – a gift.

The book lends its weight; the weight borrowed from another time and given to this.

From these few words I get: Weight. Exchange. Gift.

Empathy is a kind of exchange where you swap with another to understand the predicament they are in. What you can swap or exchange is of course limited, especially when dealing with events which are both unimaginable in their horror and/or set in the distant past.

Art itself is an exchange and that is where I want to focus my attention.

That is the starting point of this piece: not the text, but the weight of the book, the exchange. So I weighed the book: 668 grams.

Exchanging the weight of the book for the weight of something else and interpreting that weight in the form of something new is also a means of illustrating the idea of taking someone else’s life/predicament and in some small way reinterpreting it within your own.

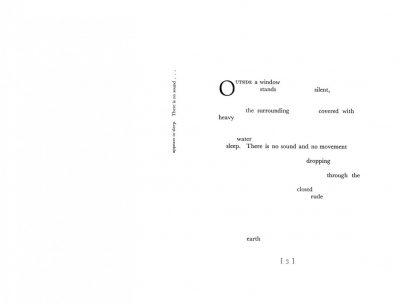

It’s also interesting that the title of the project, derived from the blackout poem, is Heavy Water Sleep (something which I saw a alluding to snow).

![14-15 [17.06.11]](https://farm4.static.flickr.com/3059/5841597001_471957f641.jpg)