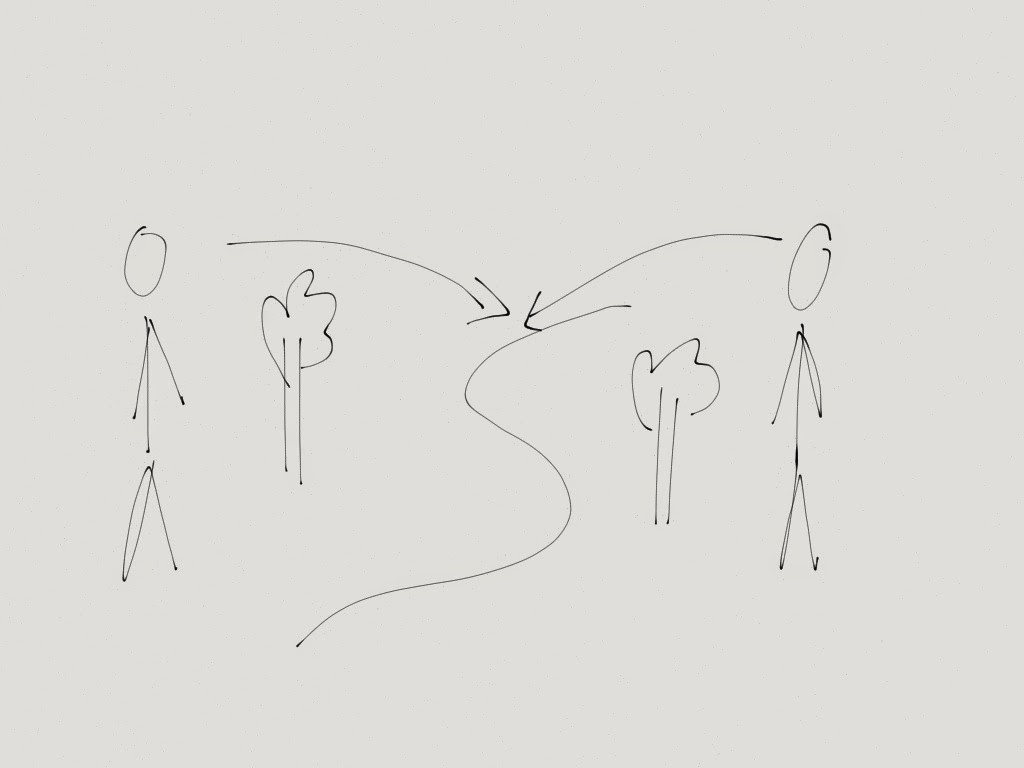

Having recently bought and iPad Pro and pencil, I decided to start drawing in a style inspired to some extent by my son’s drawings and by my recent visit to Shotover wood, and, I have to say, I was pleased with the results.

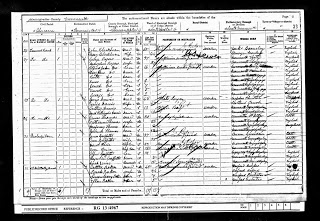

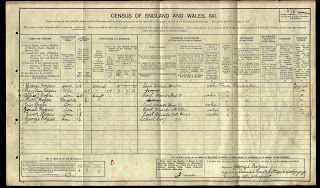

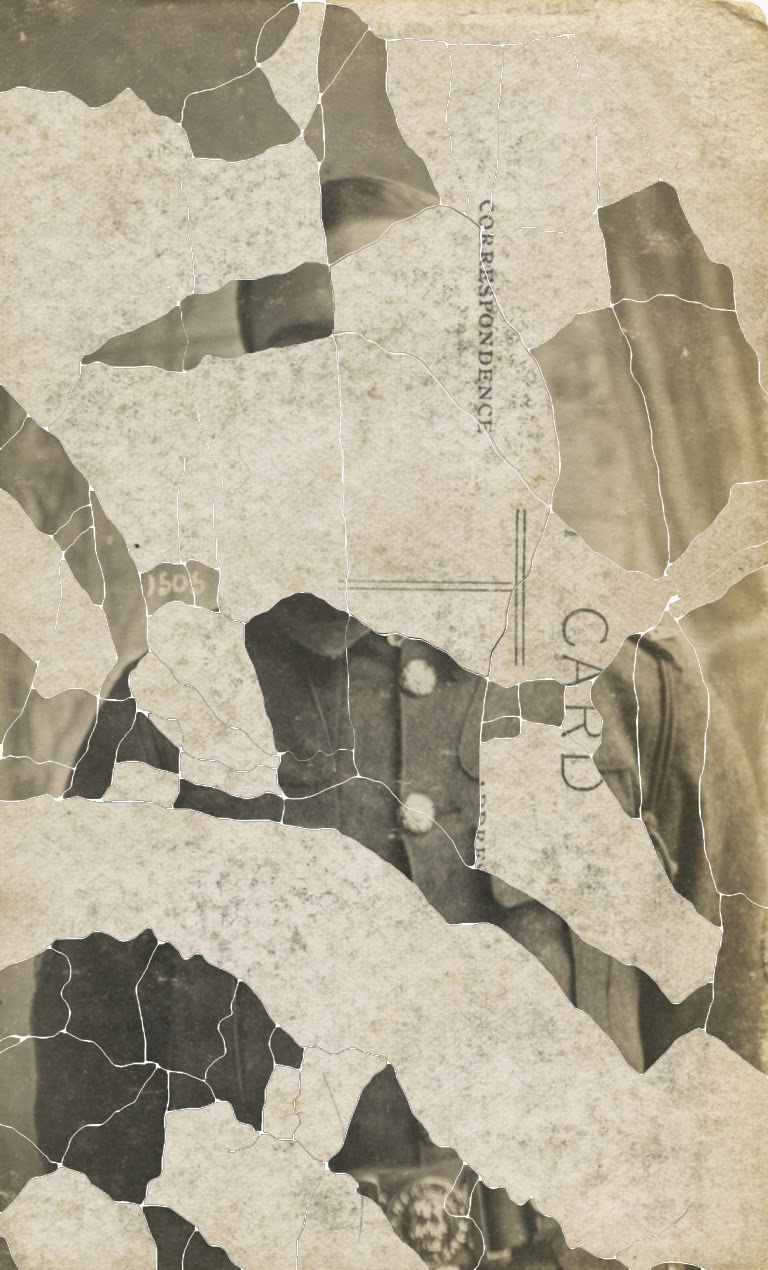

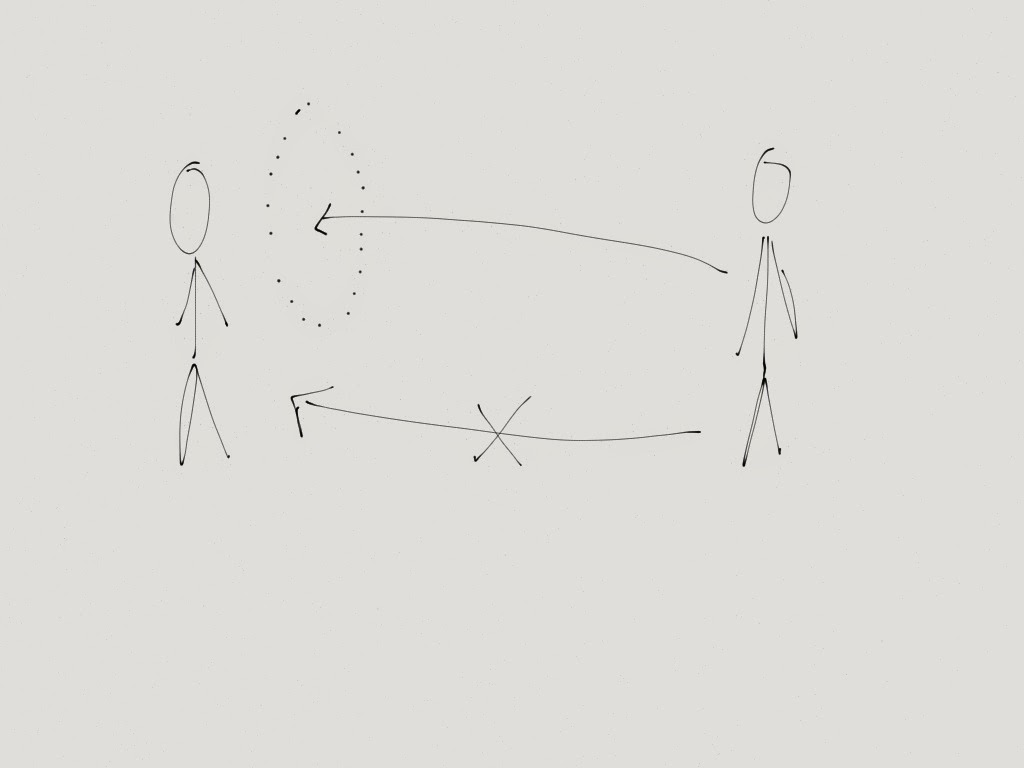

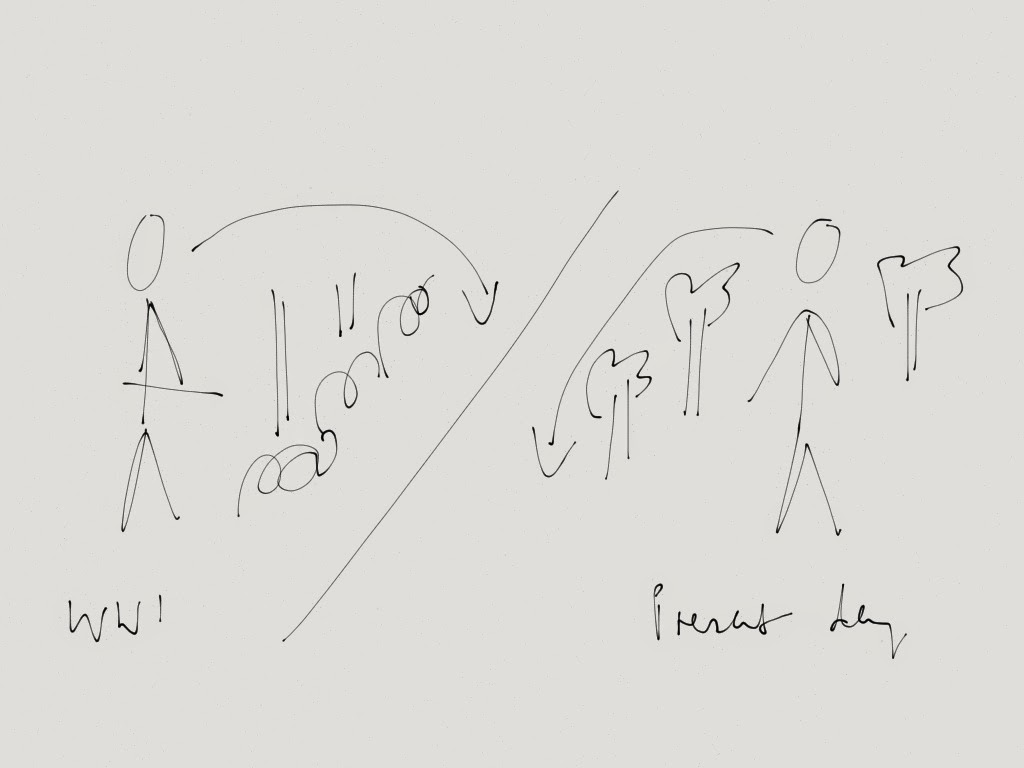

The process of drawing without too much consideration of what one’s aiming to represent is similar to the process of automatic writing, where the subconscious drives the pen. I did something like this 10 years ago after a visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau, a trip which inspired much of the work I made over the next 2 years as I completed my MA in Contemporary Arts at Oxford Brookes University. Two of the pieces that came about after various ‘automatic’ strategies are those below. First a series of drawings…

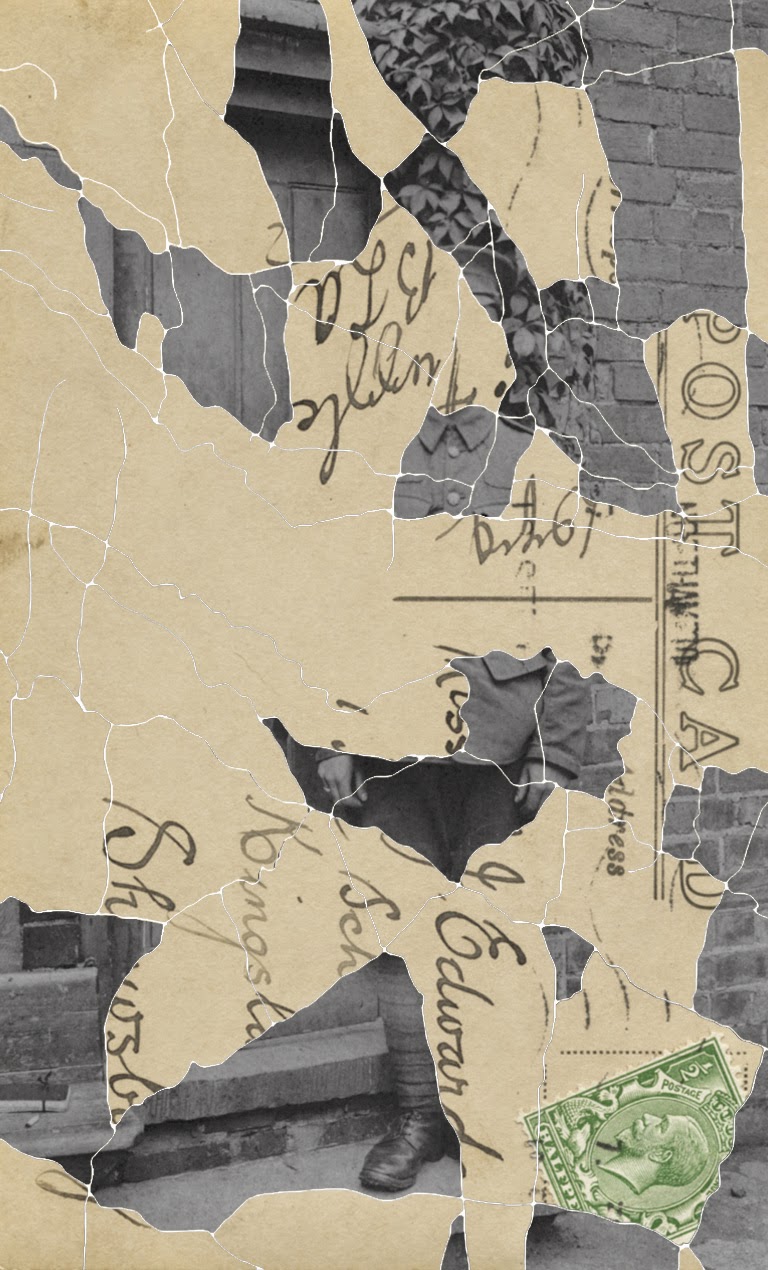

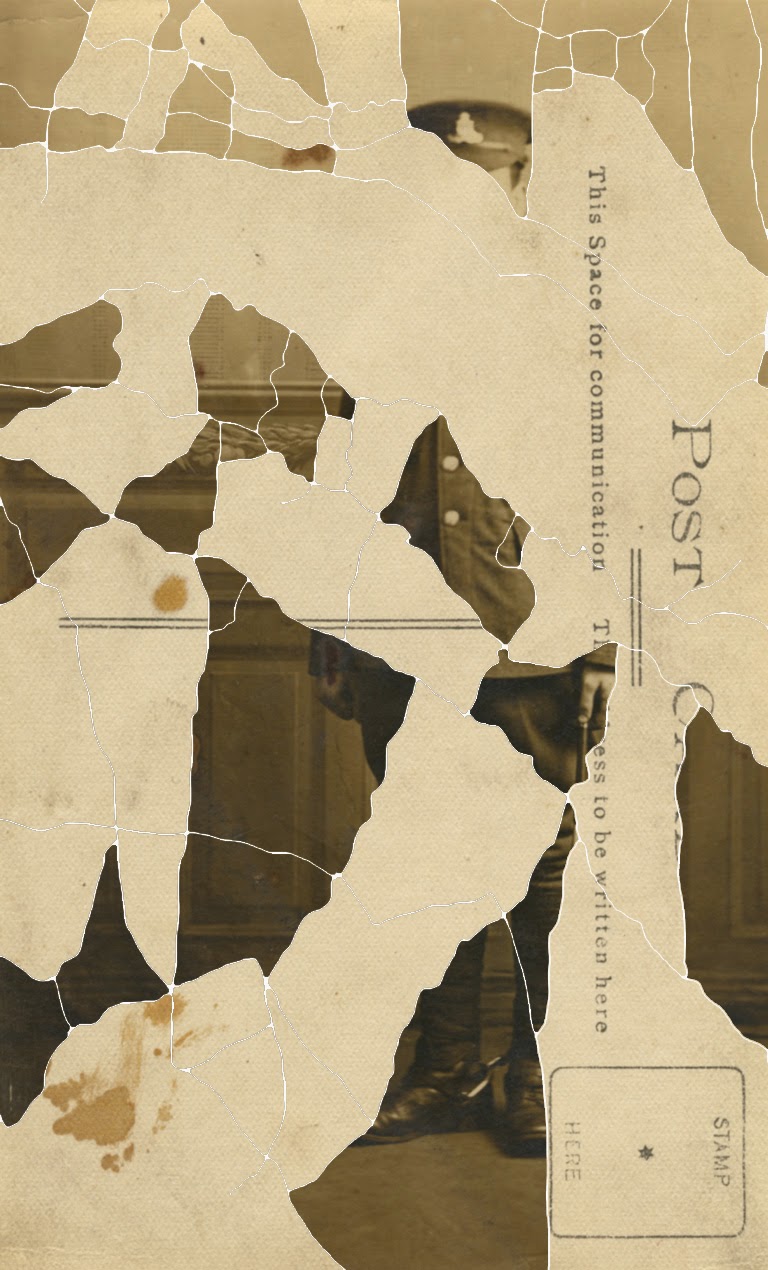

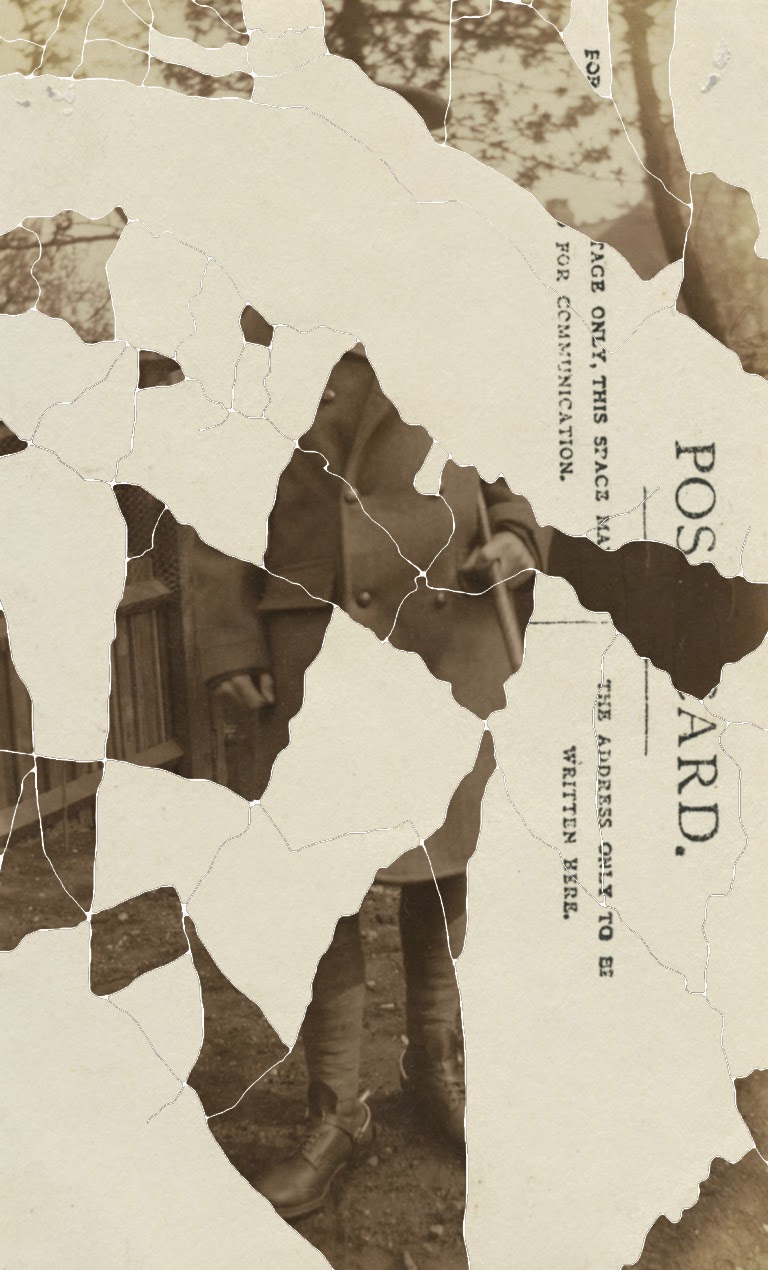

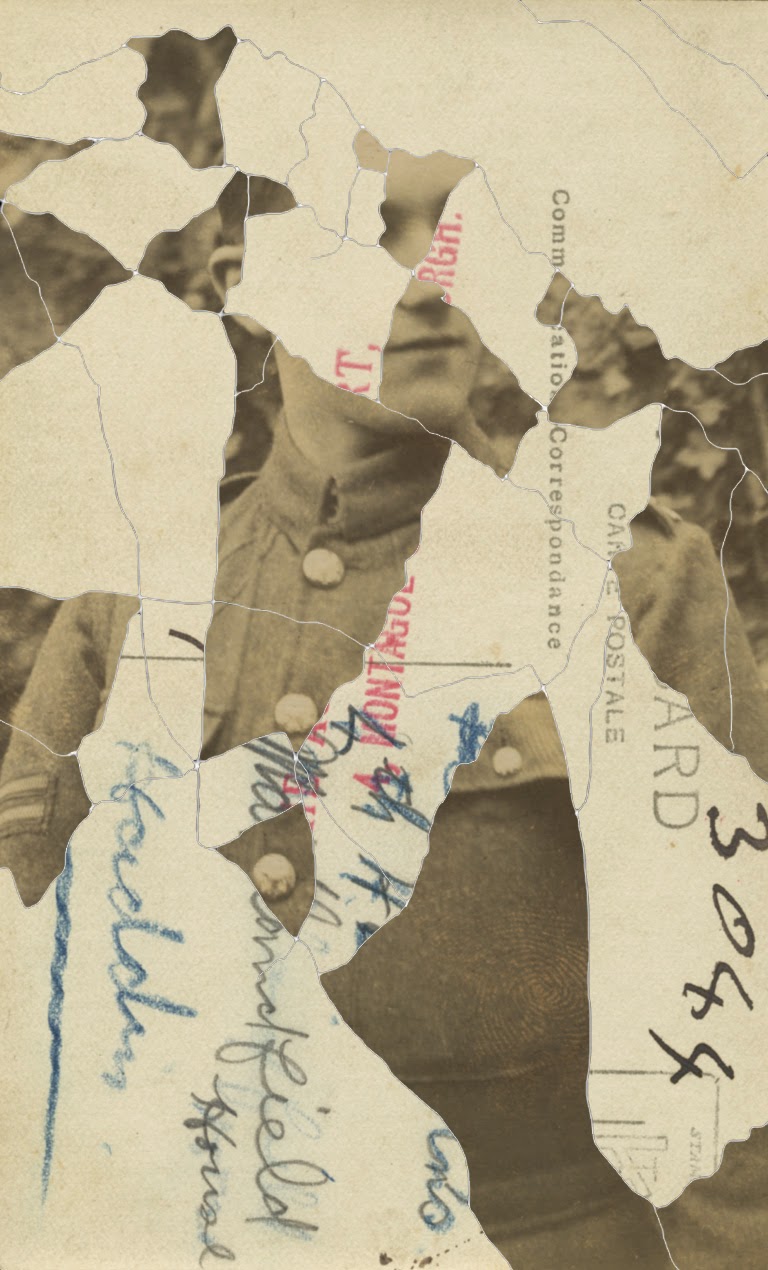

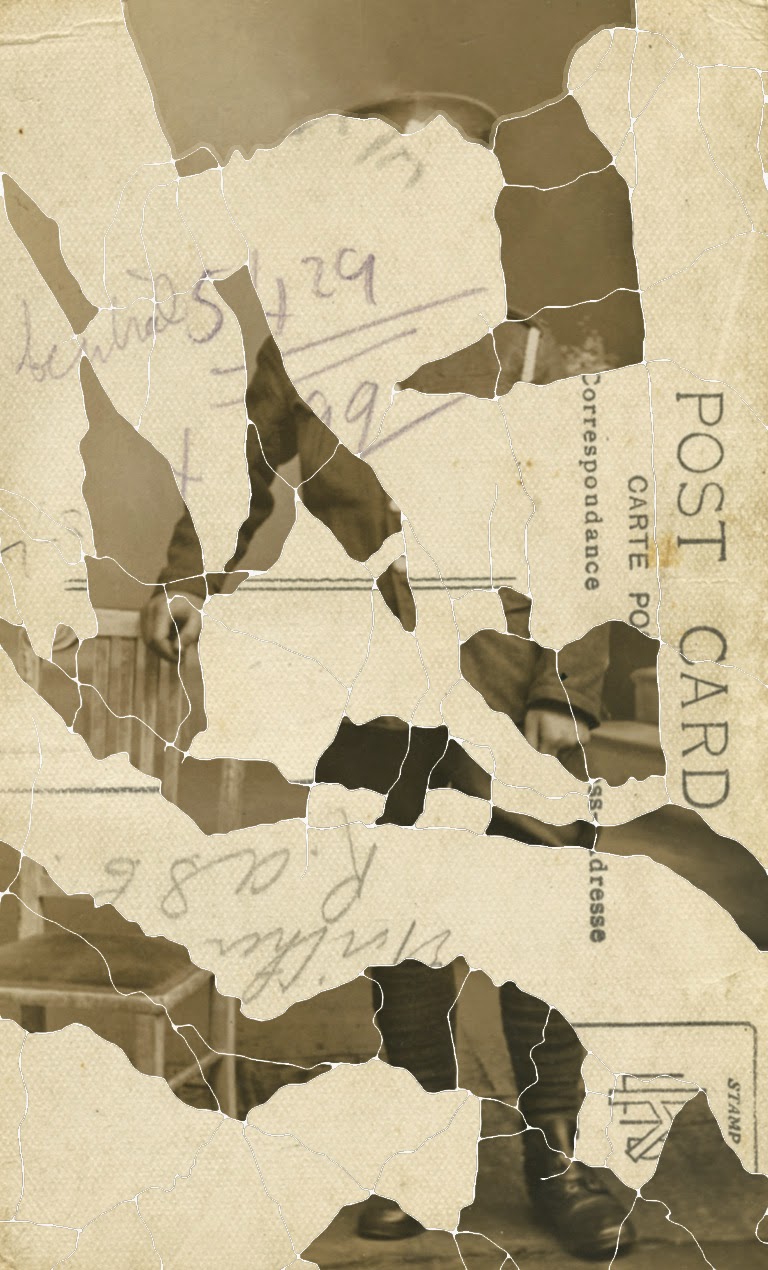

and then a series of text works…

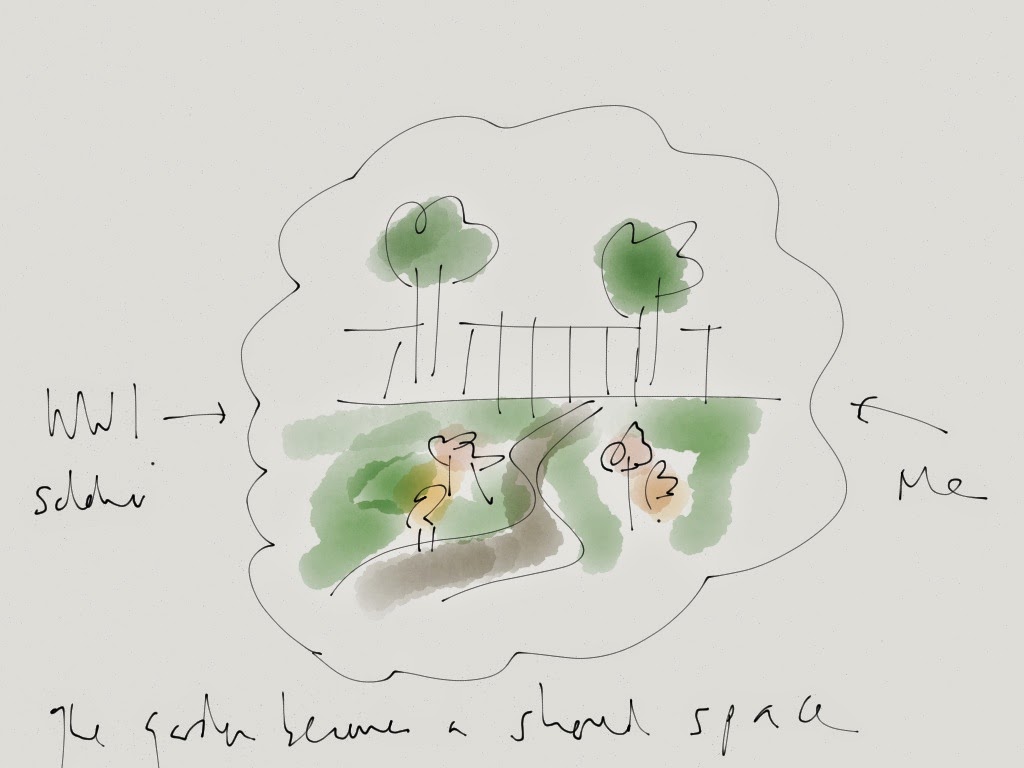

The title of this post – ‘Somewhere Between Writing and Trees’ – is to some extent a reflection of an ‘automatic’, ‘subconscious’ process and the conscious drive to a representation of trees. Trees have played an important part in my research over the past ten years and after a gap in my work of late, they are I’m sure, a means of finding my way back in, particularly when coupled with thoughts of my son. Separated from my wife, I am also separated from both my children for much of the week, a pain which, anyone in my position would empathise with. Empathy itself has been an important part of my research – in particular regarding the victims of the Holocaust and the millions who died in World War I – and trees have played a part in bridging the gap between the past and present – a necessary step towards empathy. With regards to the Holocaust, it was the way the trees moved at Birkenau which closed a gap of almost 70 years; with World War I it was a quote from Paul Fussell: “…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

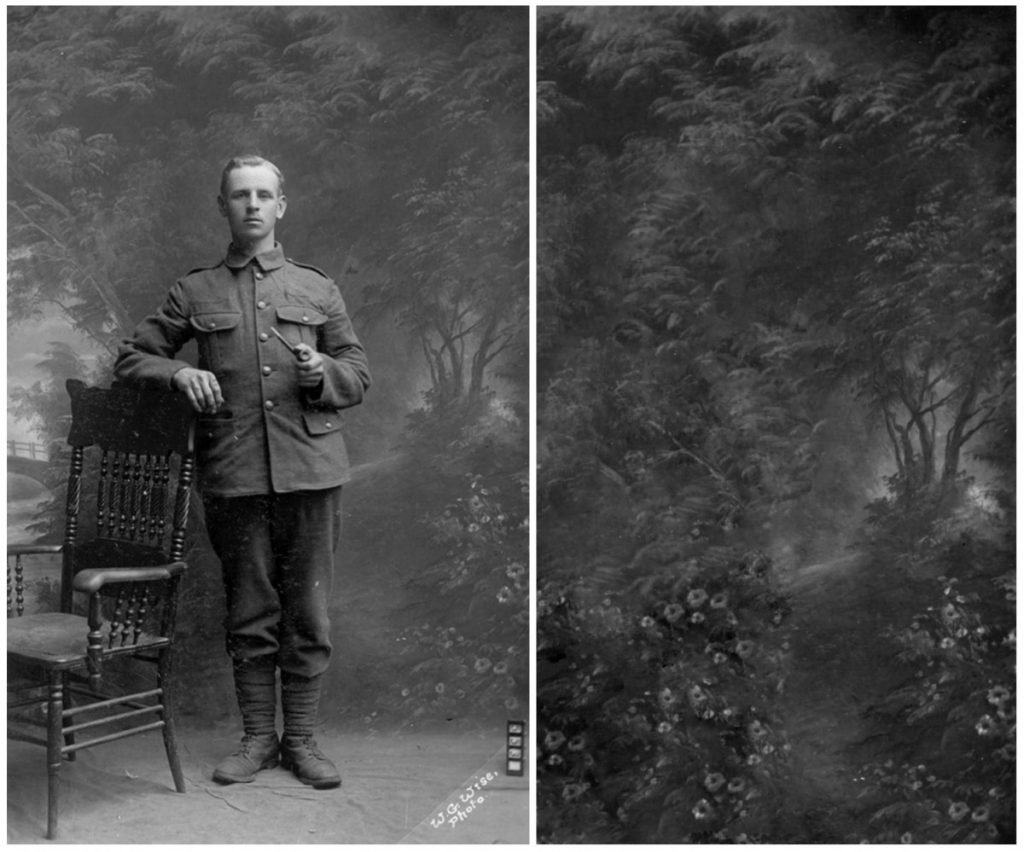

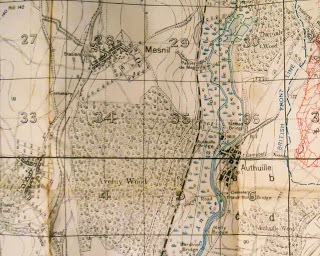

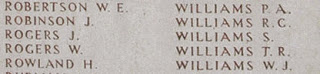

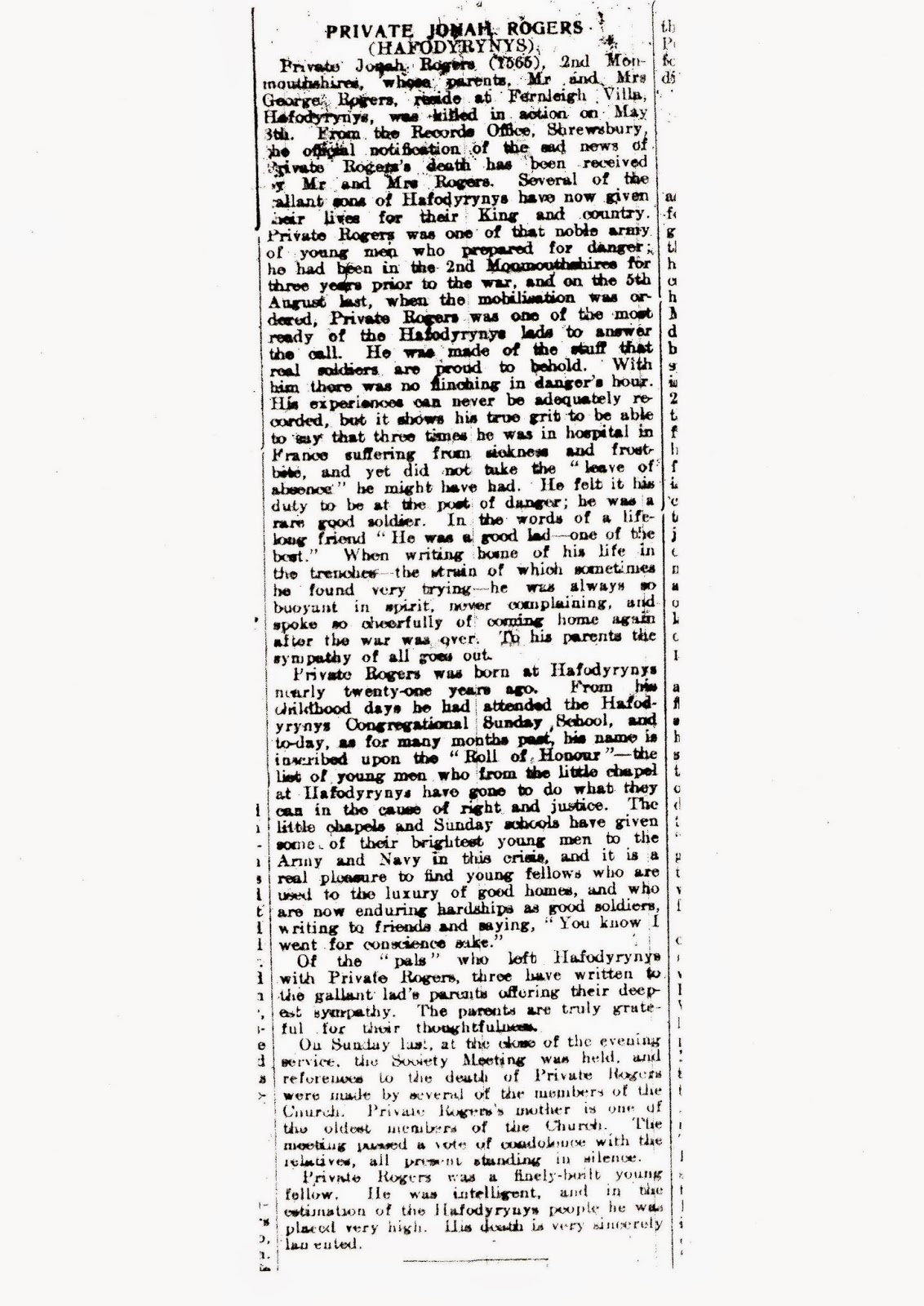

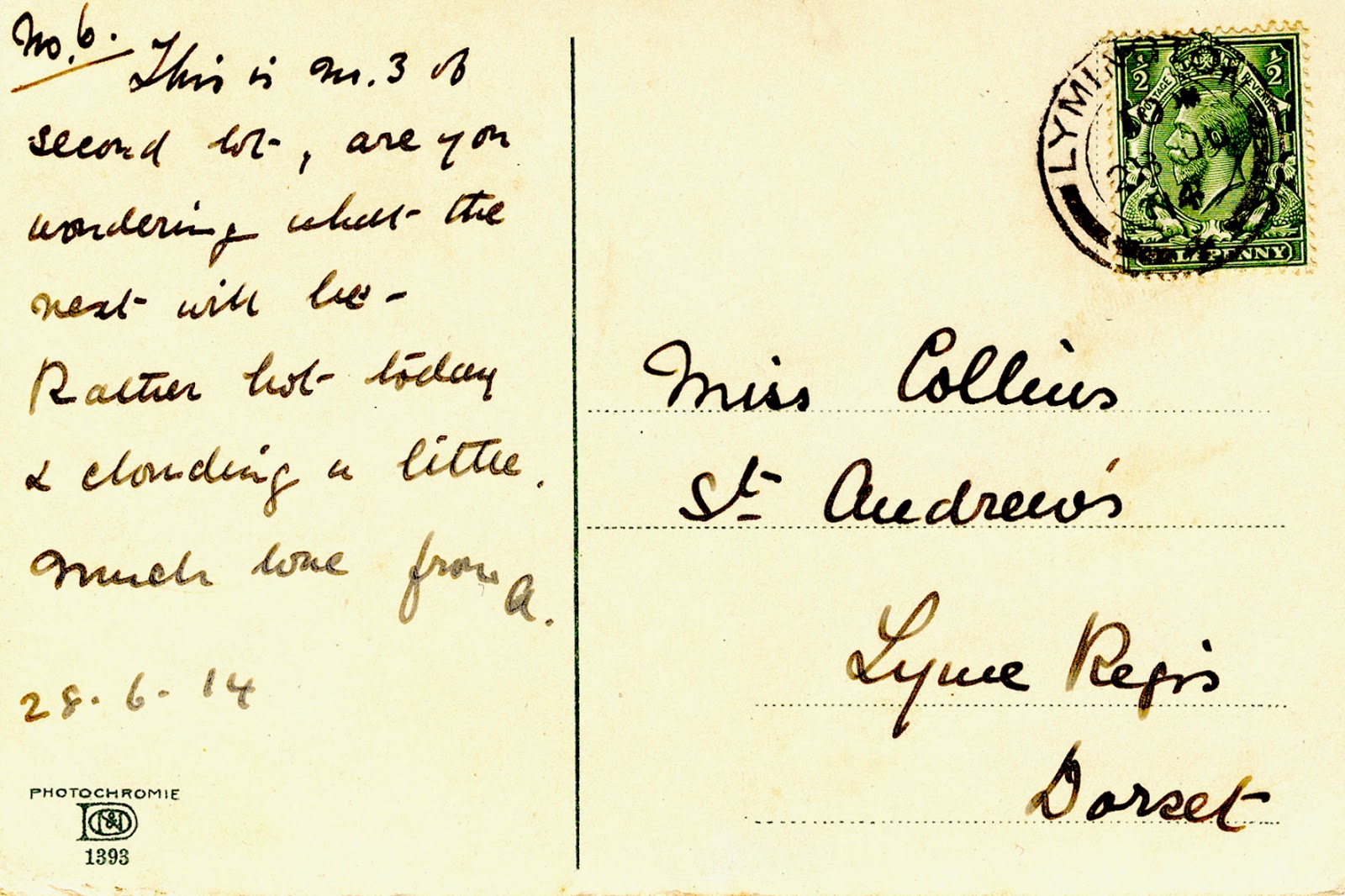

We are familiar with the image of blasted trees from the battlefields of The Somme, Ypres and Verdun, but nothing in our imaginations can take us there. We can never experience what those men had to endure, day after day, night after night. So the idea of looking for the pastoral as a means of empathising with victims of war is an important one, helping to bridge the gap by reminding us how these soldiers were ordinary men before they enlisted; men who were once boys, some of whom no doubt played in woods and climbed trees.

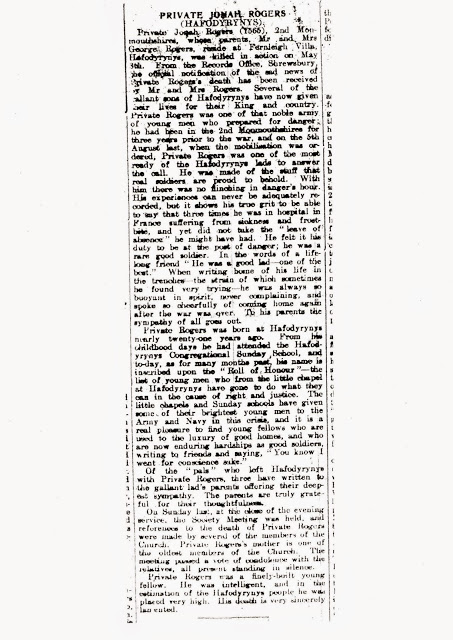

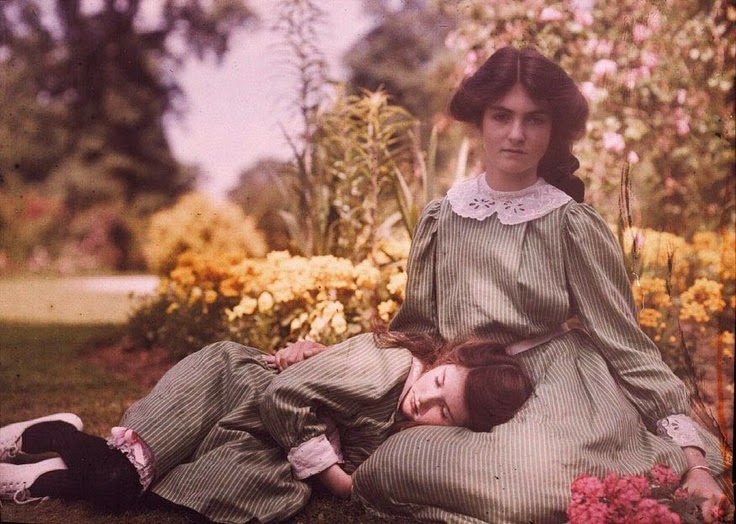

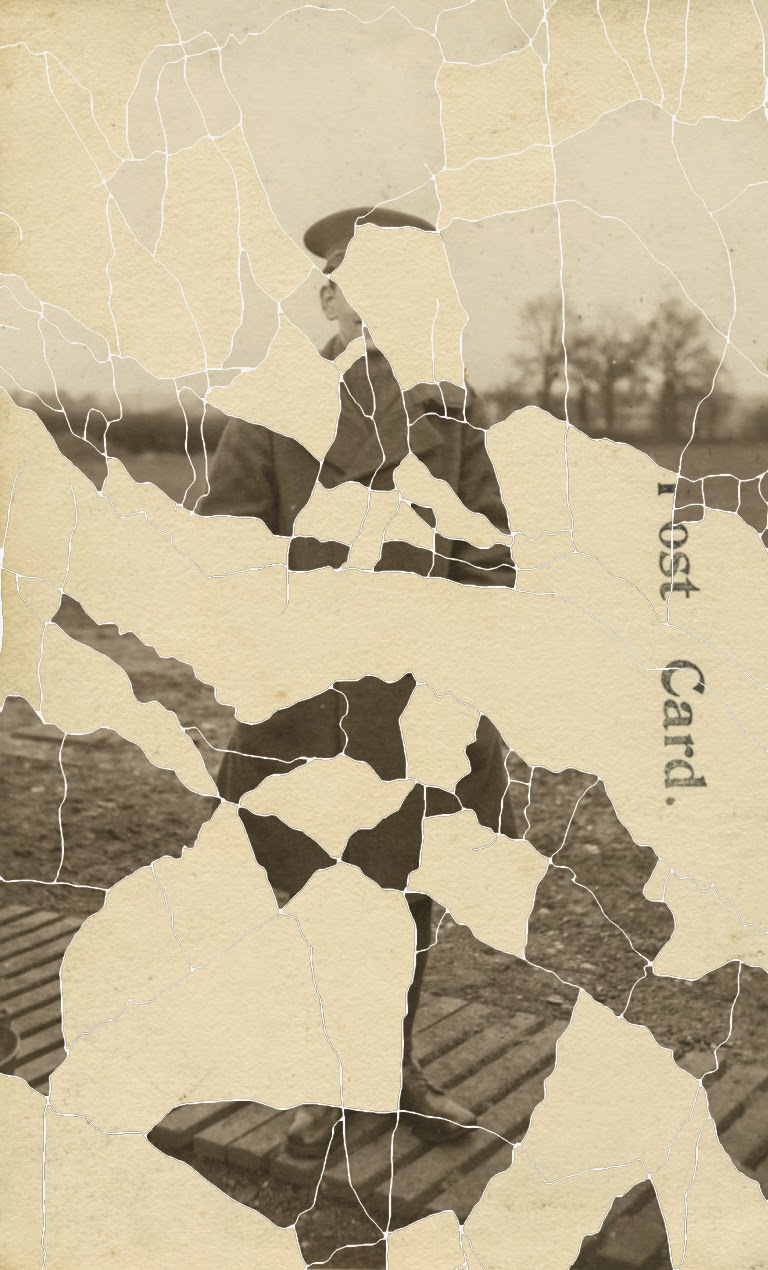

When I was a boy I was obsessed with woods and forests. Trees were a means of escaping the present, where in the early 1980s, the threat of nuclear conflict was ever present. They were a means of escaping to the past. I loved the idea of the mediaeval landscape, covered with vast swathes of trees, because, quite simply, it was a place where nuclear weapons did not exist. Of course it was an idealised past; an overly pastoral one, and to some extent the backdrops of portraits made of soldiers before they went to war remind me of this place. The following is a piece I made based on those backdrops.

Every one of these men was someone’s son which brings me back to my own, to his drawings and my drawings of trees.

Drawing and drawing with my son, helps close the gap which separates us for much of the week. It helps me feel close to him when he isn’t there. Drawing trees is a process which takes me back to my work, and whilst thinking of my son, becomes another means of empathising with those in the past.