Graveyards and cemeteries have always fascinated me. The feeling I have when entering them, is much the same as when I enter a museum, a sense of calm mixed with expectation as I wonder whose story or stories I’ll encounter.

Graveyards are archives; the headstones, documents on which we find the names and dates of those who’ve gone before us. But they are much more than that.

My family tree is an archive, one currently comprising almost 1,000 individuals. Poring through documents (albeit ones which are digitised), I discover names, locations and dates, much as you do when walking through a graveyard.

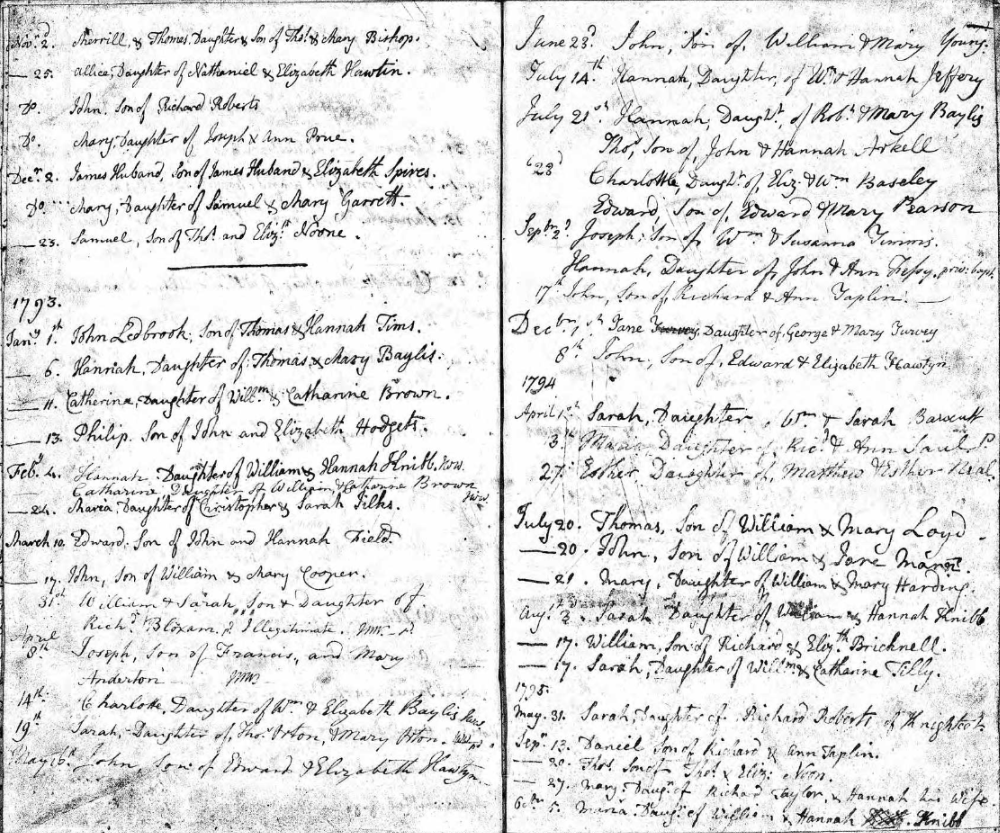

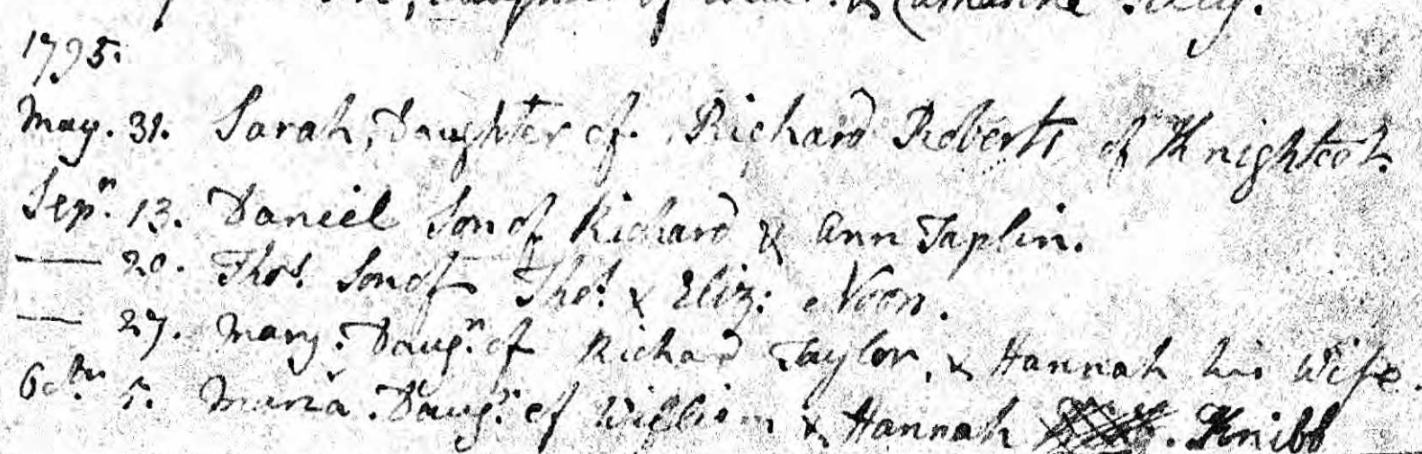

Thomas Noon was my great-great-great-great-uncle. He was born in Burton Dassett, Warwickshire in 1795. He was baptised there on 20th September.

At some point between 1824 (the birth of his daughter Betsy) and 1830 (the birth of his son Thomas) he moved with his family to Oxford.

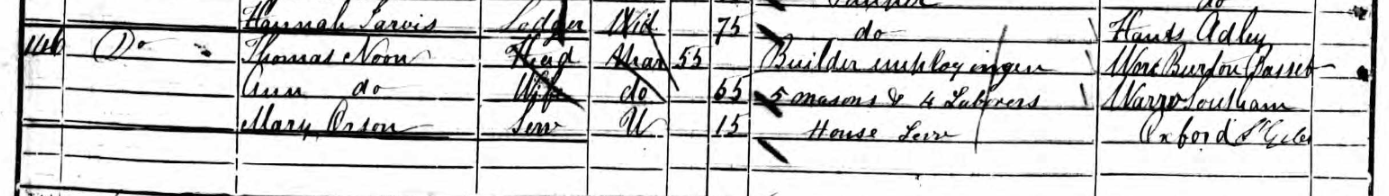

In 1841 Thomas spent census night away from Oxford, but we find him in 1851, along with his second wife Ann.

By this time Thomas had already buried his first wife Mary (1832 or 1840) and their three daughters – Emilia (1837), Eliza (1846) and Betsy (1850). In September of this census year, Thomas would also bury his son, killed in a train crash at Bicester. In 1852, tragedy would strike again when his brother Elijah killed his own wife with a sword at their house in Jericho.

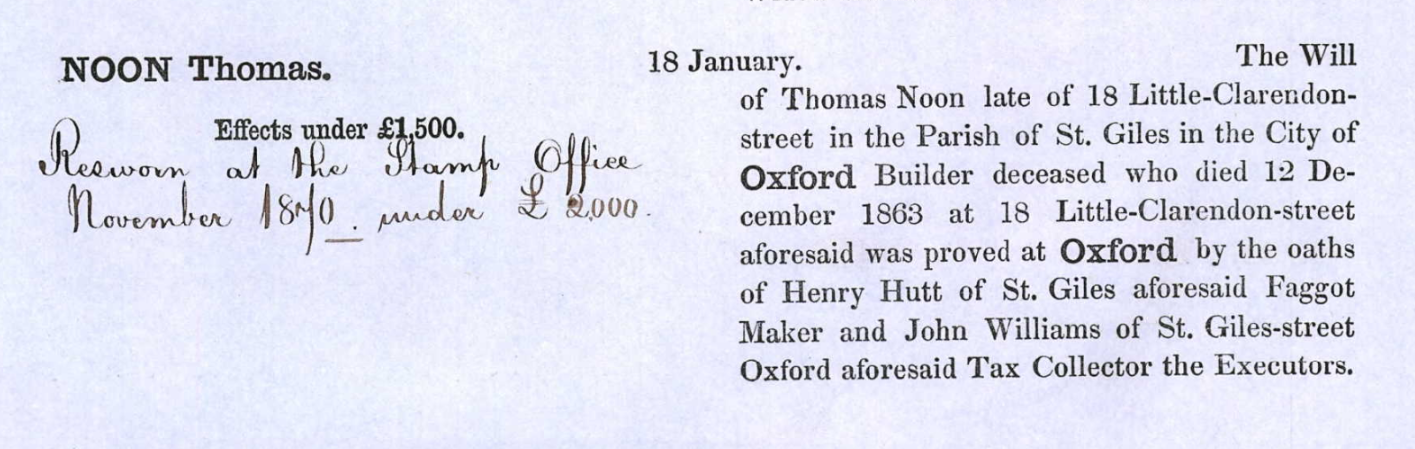

Thomas died in 1863 at his home in Little Clarendon Street.

Through archive sources we can piece together his life, in censuses, baptism records, probate records and newspapers.

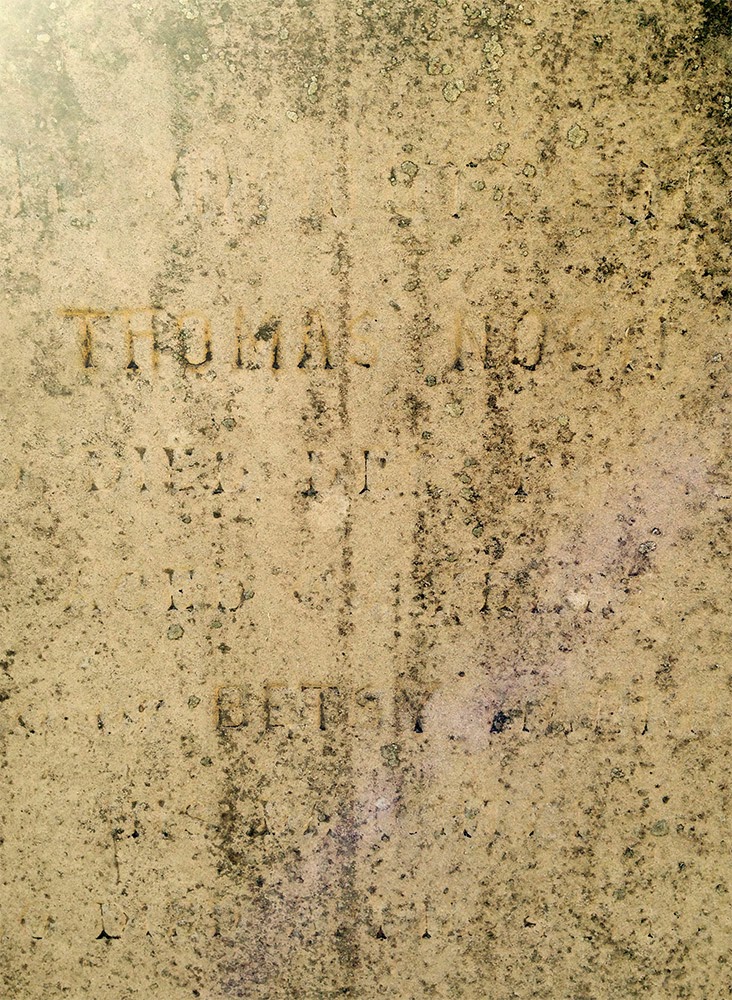

As we consider his terrible losses, we can sympathise with him but standing at his grave, the one he shares with his son Thomas and his daughter Betsy, that sympathy turns to empathy.

Like the name Thomas Noon, found in the documents described above, we find the name on his gravestone (below), weathered and worn to almost nothing (NB the name Thomas Noon and Betsy have been enhanced).

I can trace his name with my finger, and as I stand there, looking down at the grave, everything changes. I might be thinking, but my body is mourning.

First Betsy and then Thomas Jr were buried in that very grave over a decade before their father. How many times in those intervening years did Thomas stand where I was standing, looking down at that same patch of ground, thinking of his children? It’s as if, standing there over 150 years later, with the bearing of a mourner, I not only find Thomas within my imagination; I find myself within him too.

I can imagine him there, listening as I can to the wind in the trees. He sees the same late-winter sun and feels its warmth on his face. I can, as I have done, read about his children and their untimely deaths. I can read about him. But standing at their grave, my imagined versions of them are augmented by the gesture of my body.

They move in that space where the boundary between imagination and memory is blurred.