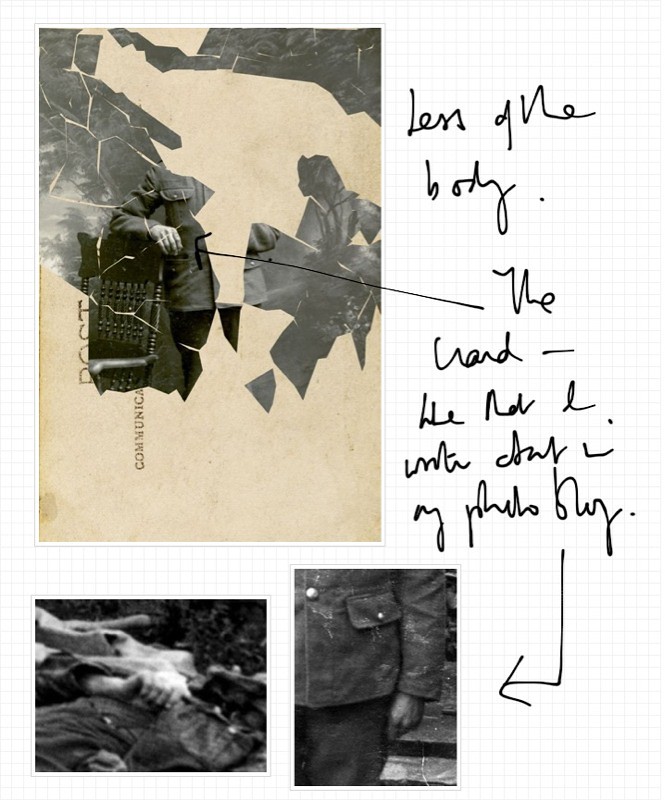

I’ve been working on the theme of backdrops lately, using those in early 20th century portrait photographs such as that below.

To begin with, I remove the figure standing in front and then, using Photoshop, fill in the blank sections where the figure has been removed.

I have then extended the ‘canvas’ using Photoshop to generate missing information.

This fits in nicely with the idea of reimagining the past, where those who lived are obviously missing and what we are left with is a fragment from which we have to build an imagined view of the past to stand in front of.