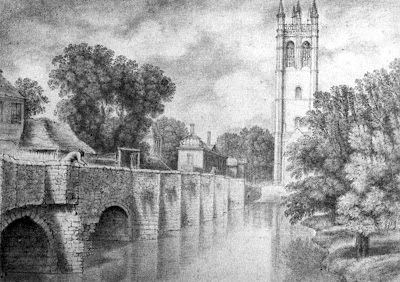

The following is a drawing made by John Malchair showing the causeway of what is now Abingdon Road. The rather unusual building is Friar Bacon’s Study which was demolished in 1779. Beneath the drawing is a photograph showing the same causeway, with two arches, a little bit like the arch which can be seen in the drawing.

Ghosts of the Church of St. Clement

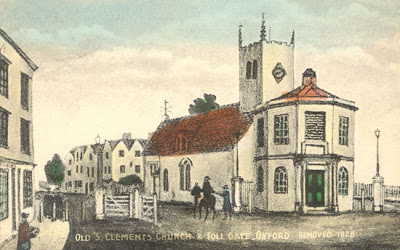

The old church of St. Clement, built around 1122 is a principal character in our story. It was described by the antiquary Thomas Hearne as “a very pretty little church,” but unable to serve the growing population of the parish, it was demolished in 1828 and a new church built on Hacklingcroft Meadow in Marston. The church’s three bells (one of which is the oldest bell in Oxford, dating to the 13th century) were taken to the new building. The church’s graveyard remained until 1950, when it too disappeared with the construction of The Plain roundabout.

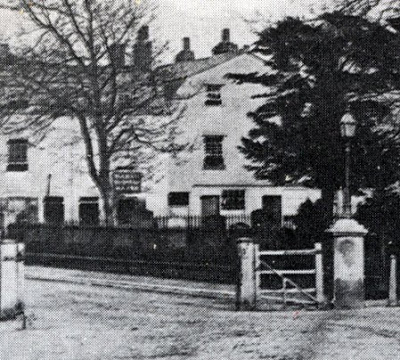

The toll house in front of the tower remained until the construction of the Victoria Fountain in 1899. The photograph below, taken in 1868, shows the old toll house and the churchyard behind.

Looking closely one can see the gravestones…

…and the ghosts of those who walked too fast.

It’s interesting to compare the image above with the text of the newspaper notice. Both contain the likeness of a man on the same stretch of road, and yet that created 100 years earlier with words is, somehow, all the more clear. With the image above, we feel the same sensation as when we look at other very old photographs; a kind of vertigo which links – through a ‘carnal light’ – two poles of simultaneous existence and non-existence. We look at the image of a man in a time when he doesn’t exist, while he looks back from a time when we have yet to be born. Here we both are, and aren’t at the same time. The light, captured in the image, is, like an “umbilical cord” which as Sontag says, “links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze – light though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.”

In truth, we share this skin with anyone who’s ever been and it’s through our bodies that we identify with those who’ve gone before us. With the text, our sense of the man comes not only through that which the words describe, but through the questions it asks and leaves unanswered. Furthermore, there is a sense of movement in the writing. We not only get a snapshot, but a full few minutes of this anonymous man’s life – a seemingly insignificant moment which serves, ironically, to make him all the more clear. It’s as if the blurs in the photograph above, caused by the long exposure and the movement of those in view, were instead a piece of film, one in which we don’t see a ghost, but a living, breathing individual.

This sense of movement is of course something we also share, and it’s this kinaesthetic aspect of the text which seems to count the man – whose more than likely been dead for more than two centuries – among us. Because I’ve walked and experienced the insignificant, ‘everydayness’ of moments on the bridge, I seem to know him better than, for example, I do the man who stands against the toll house in the photograph. The man and the toll house have both disappeared. But the line of movement, the narrative line, and therefore the stranger of our tale, persists to this day.

The Narrative Line

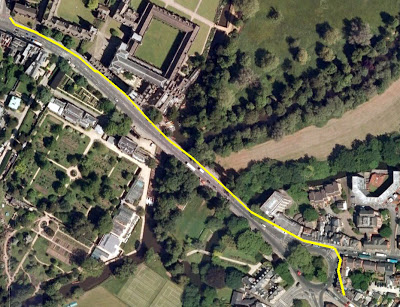

With my GPS, I traced the route we know the Gentleman’s Servant took across Magdalen Bridge up into modern day Cowley Road. It was hard to imagine the scene in 1770 when the road would have been much quieter. Cars, buses and motorbikes were everywhere, the sound of their engines blocking out almost everything else.

But nevertheless, as I walked, I tried to take in everything around me, to capture all that made the present moment what it was, for even though the same place in 2010 is light years away from what it was 240 years ago, nevertheless, when the stranger rode over the bridge on December 12th 1770, it was something which for him was happening in the present. Now this might sound an obvious thing to say, but often when we read about the past, it’s almost as if we’re reading a fiction – a story which has a beginning, a middle and an end, and in which the characters follow a proscribed route laid down by the author: the narrative line in this instance comprises the text which makes up the tale. Of course life isn’t like this. When we walk, even if we’re going somewhere particular, we walk without knowing what may lie ahead of us. We might well know where we’re going, but how we’ll get there exactly, and what will happen as we travel, is something we only discover in the present moment.

As I wrote as part of a recent exhibition:

The Past is Time without a ticking clock. A place where paths and roads are measured in years. The Present is a place where the clock ticks but always only for a second. Where, upon those same paths and roads we continue, for that second, with our existence.

I want to read history in terms of its seconds – the small spaces within which life really happens. Every second in the present day – every moment – is a lens through which we can glimpse the past, no matter how distant it is. The more we know about the past (in particular the ‘geography’ of whatever we’re researching) the better the picture. But something in the space of every second reminds us, that what happened in the past happened in what was then a present just like ours; something as a simple, for example, as trees blowing in the wind.

The narrative line is like a piece of text; we follow it as we follow the words of a sentence, putting one foot in front of the other. But reading between the lines, we fill the gaps with what we see and experience around us. We are reminded that the stranger was moving all those years ago, unaware of what might lay before him. We become aware that he could feel the wind on his face, that he could see the sky, the river flowing beneath the bridge. And as we think, we realise that he himself was thinking, as was everyone around him – and this is the key to answering the questions I posed at the beginning of this project.

Every second the stranger rode along that line, he was part of a complex web of connections. These moments comprising his story were moments in many others – countless stories in a plot more complex that we can imagine. The more we know about these moments, the more we can picture the scene and all who lived at the time, the better the chance we have of finding answers.

As I walked the length of the line, I looked to my right and glimpsed the 17th century gateway to the Botanic Gardens, and in that gesture, I found a connection with the stranger. The gateway is a witness to the moment I’m researching, and looking at it is one way of asking it for an answer.

John Gwynn’s Survey 1772 – Pt 2

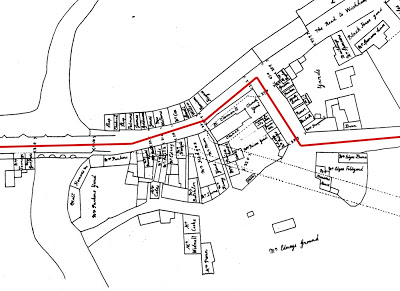

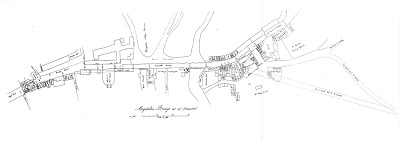

Whilst looking through some old research I did a few years ago, I came across the drawing reproduced below of Magdalen Bridge and its environs taken from John Gwynn’s survey of 1772.

It shows the route we know the stranger took – the narrative line of this story – on December 12th 1770 along with the names of those who lived or owned properties bordering the street in 1771/72. Interestingly, my namesake – at least as far as my surname goes – owned property just in front of the old church of St. Clement which was demolished in 1828.

Magdalen Bridge c.1772

The image below is a drawing of Magdalen Bridge made around 1772 by the German artist John Malchair. Following the passing of the Mileways Act in 1771, Malchair made a number of studies of the old bridge so as to record it for posterity.

With various parts of the mediaeval city threatened because of the Act, Malchair drew a number of views of buildings and structures including the North Gate and Bocardo Prison and Friar Bacon’s study which eventually fell in 1779.

This then is the bridge over which The Gentleman’s Servant crossed with two horses on December 12th 1770.

John Gwynn’s Survey 1772

Remarkable evidence of those who lived in Oxford around the time the notice appeared in Jackson’s Oxford Journal can be found in a survey carried out by John Gwynn in 1772 (John Gwynn also designed the new Magdalen Bridge). Made as part of continuing improvements originating with the Mileways Act of 1771, the actions of Gwynn (who could be seen around town measuring the fronts of houses and other buildings) aroused suspicion and even alarm among the city’s residents. The survey itself was required to calculate the costs of repaving the city’s streets for which each property was liable to pay a share depending on the size of their facades. What we have as a result is a wonderful record; a long list of names of all the city’s residents (or rather property owners), the streets on which they lived (or owned property) and the size of their dwellings – given in yards, feet and inches. It’s interesting for me that among the many Stevenses listed in the survey might well be my great-great-great-great-great-grandparents.

The page reproduced below, is taken from the survey and represents the bottom end of the High Street where it meets Magdalen Bridge – the Bridge can be seen listed below the name of a Dr. Sibthorpe. The Physick Garden above, is the old name for what is now the Botanic Gardens.

See also John Gwynn’s Survey 1772 – Part 2.

Magdalen Bridge 2010

Although the present bridge is not that over which the enigmatic stranger crossed, it nonetheless marks the line he travelled and along that line are witnesses to the moment I’m researching. Below are a few photographs which I took today showing the famous landmark.

Magdalen Tower (above), as seen from the east, was completed in 1509 and would have seen the stranger pass below on his way over the bridge towards what was then the Watlington Road. The image below shows the route he would have taken with his two horses, from Magdalen Bridge on the right of the picture, towards what is now The Plain, but which in the stranger’s day would have been the church and churchyard of St. Clement, demolished in 1828.

The roundabout (below) stands on what was once the church and churchyard of St. Clement . To the right is the fountain, built in 1899 as a belated tribute to Queen Victoria who celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. This was built on the site of the old toll house. The houses in the background stand on modern-day Cowley Road, the road up which the stranger rode into obscurity.

As I walked up the bridge I wondered who had seen the stranger pass and where they’d been when they saw him riding the two horses. In terms of more witnesses, the walls of the Botanic Gardens (founded in 1621) and its gateway (built by Inigo Jones’ master-mason Nicholas Stone in 1632) would have been standing at the time. The two statues and the bust, positioned in the gateway still look towards the road…

…and I like to imagine their eyes would somehow have seen him.

Magdalen Bridge

The bridge over which our Gentleman’s Servant rode in December 1770 is not the same bridge which crosses the River Cherwell today. Being as it is an important part of the story, I’ve copied an entry on the bridge from The Encyclopaedia of Oxford1 which I’ve reproduced below.

A bridge, formerly known as Pettypont and East Bridge, has stood here since at least 1004. In the Middle Ages the cost of its upkeep was shared between the county and the town, the town meeting its three-quarters share largely by alms and charitable bequests, the maintenance of bridges being then considered a pious duty. Bridge-hermits were also appointed to help travellers with any difficulties they might experience in crossing. The original bridge was of wood, but by the 16th century a stone bridge, some 500 feet long, with about twenty pointed and rounded arches, had been constructed.

At this time the city was still paying for repairs, both by taxation and by the allocation of alms; but William of Waynflete, the founder of Magdalen College, may have paid for restoration of the bridge in the 15th century, and the University certainly did so in 1723. Although a major restoration was then undertaken, less than fifty years later some of the piers had been swept away by floods and the western end had collapsed completely. Condemned as dangerous, it was rebuilt between 1772 and 1778 under the provisions of the Oxford Improvement Act of 1771, to the design of John Gwynn. At the same time a toll-house was built at The Plain, with gates across the roads from Headington to Cowley to collect dues for the maintenance of the bridge. Twenty-seven feet wide, with recesses in the middle, the bridge’s large semi-circular arches were supplemented by smaller ones over the towpaths. The plain balustrade was designed by John Townesend after plans for a more elaborate one had been dropped. The bridge was widened in 1835 and again in 1882. Notabilities have frequently been welcomed or taken their official departure at the bridge, as Queen Elizabeth I did on leaving Oxford in 1566.

1 The Encyclpaedia of Oxford, 1988, Ed. Christopher Hibbert, Assoc. Ed. Edward Hibbert; London, Macmillan London Limited

To Name Him Would Almost Be To Kill Him

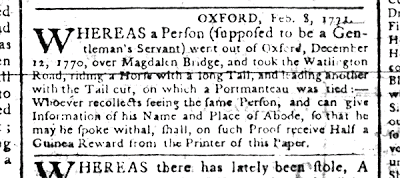

If you visit the Westgate Library in Oxford, and make your way to the second floor, to the centre for Oxfordshire Studies; if you ask to see the microfilm of Jackson’s Oxford Journal for February 9th 1771, you will find, somewhere within its pages, the following notice:

“Whereas a person (supposed to be a Gentleman’s Servant) went out of Oxford, December 12th 1770 over Magdalen Bridge and took the Watlington Road riding a horse with a long tail and leading another with a cut tail on which a Portmanteau was tied: whoever recollects seeing the same person and can give information of his name and place of abode so that he may be spoke withal, shall on such proof receive half a guinea reward from the printer.”

This enigmatic text contains just 80 words, but many questions come to mind when I read it.

Who was this man?

Where was he going?

Who was he working for?

What was in the portmanteau? And who wanted to know?

What had he done that the need to ‘speak withal’ was worthy of a reward? And why was the notice only published two months after the man had left town? Would anyone recall seeing him so long after the fact?

The man described has left neither name nor grave to posterity. Indeed, all that would seem to remain is this footprint of sorts, one comprising a few words in a text pregnant with secrets, lost in the pages of a long forgotten paper.

In the first book of his epic masterwork, À la Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time) Marcel Proust writes:

“…we each derived a certain satisfaction from the mannerism, being still at the age in which one believes that one gives a thing real existence by giving it a name.”

The man described in our newspaper clipping doesn’t have a name. Does it mean therefore he has – or rather had – no real existence? The answer to that is of course, no. Certainly he’s dead, but whereas the Dead so often leave their names (as Rilke so beautifully put it in The Duino Elegies, ‘as a child leaves off playing with a broken toy’) in documents, monuments, cemeteries and so on, this man has left something else entirely. To name him would almost be to kill him.

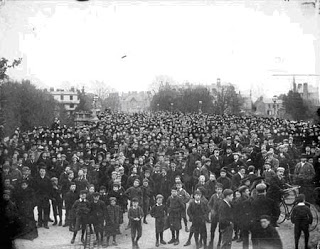

In many respects he’s not unlike those nameless men and women one often finds in old black and white photographs, for example that below, taken on the same bridge 125 years after the stranger crossed it.

What’s most intriguing about the notice, is the scene it depicts. Despite its few words we can nonetheless form an image of something which happened long before we were born; a scene in which the most insignificant detail we can imagine – perhaps a leaf fallen from a tree drifting on the river below the bridge – was more a part of the world than we as individuals – as impossibly unlikely beings – were ever, at that moment, likely to be; even my great-great-great-great-grandfather, Samuel Stevens, born in Oxford in 1776, and to me impossibly distant, was just a step away from not being born at all.

A more ‘equivalent’ image to the text might be the detail below:

Taken from a photograph, itself taken (as far as I can tell) some time in the 1920s, it’s part of a wider view of Magdalen Bridge facing west towards Magdalen Tower. No-one in this photograph is aware the picture’s being taken and in this sense it’s a genuine representation of history; an insignificant, everyday moment in time.

This project – The Gentleman’s Servant – will set out to answer the questions posed above in full knowledge of the fact that it will fail. But what interests me is, not so much the answers, but the process of looking: of researching, collecting, archiving and storytelling.