Through my research on World War I, I’ve accumulated a large amount of data – postcards, quotes, maps, texts, photographs, personal thoughts and experiences – which I want to start distilling into a new body of work. To do that, I’ve been looking for a ‘lens’ through which I might look again at this archive and thus begin shaping my research into something I can use in a work.

Quotes

A lens could be anything; an image, an experience, a thought, or in this case a quote – or quotes. I’ve discussed them before, but here they are again, the first from Neil Hanson, the second, Paul Fussell:

“As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.”

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

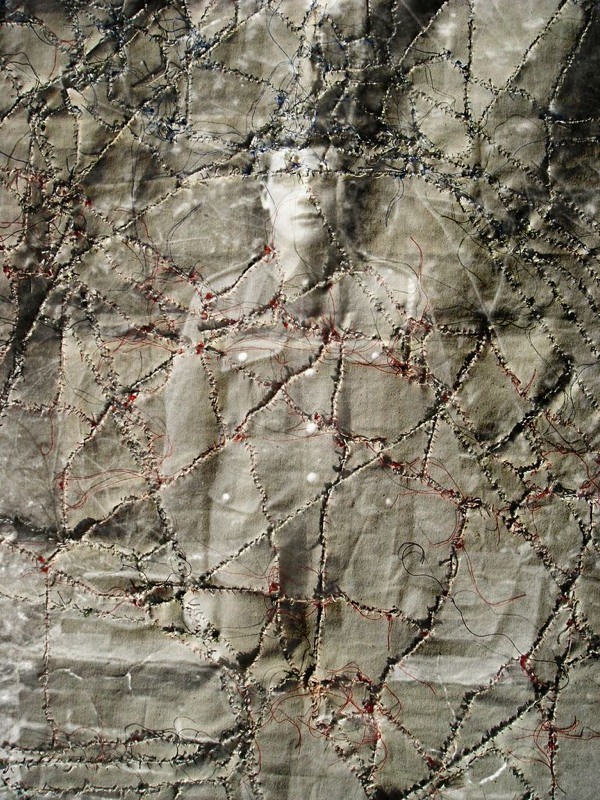

The smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – and the idea of moments of pastoral come together to make a lens through which I can re-examine my research. I’ve used Neil Hanson’s quote before, as the title of a piece in 2007 (pictured below), but combined with Paul Fussell’s quote it becomes even more interesting.

The smell of fresh cut grass is a smell I often associate with the past, in particular, my childhood, and as a child, my notion of the past was a pastoral one. To me, the past was an unspoilt place, where squirrels could run the length of the country without touching the ground (a ‘fact’ I always loved). I loved the idea – and I still do – of untouched swathes of forest.

The past was always pastoral.

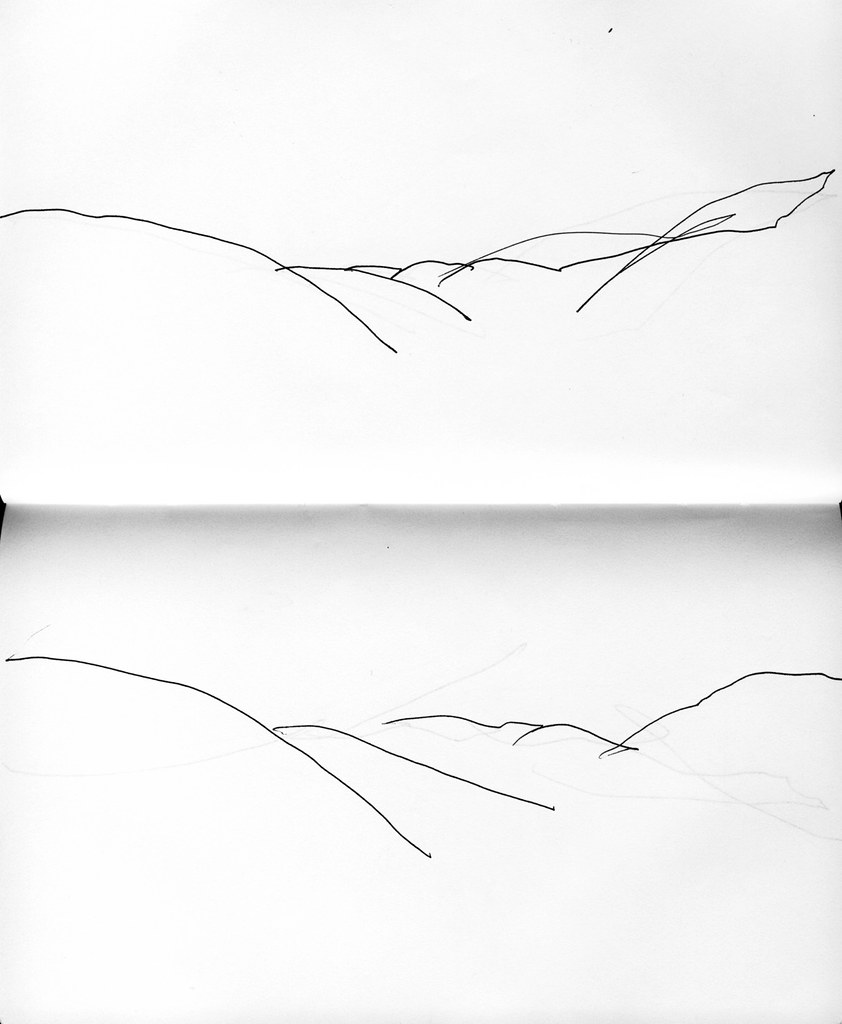

Maps

To pursue my pastoral fantasy, I would create maps of imagined landscapes (something I’ve also discussed numerous times before) and this too has become a lens through which to look at my research. When we think of those who fought in World War I, we often consider only their deaths. We don’t imagine their lives beforehand, especially the fact that not so long before the war, many were still children.

My maps were well-wooded.

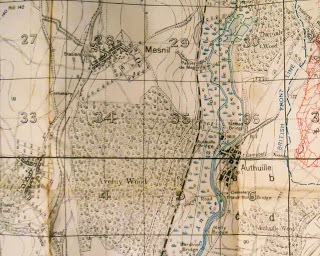

As are the trench maps I have in my collection.

Postcards and gardens

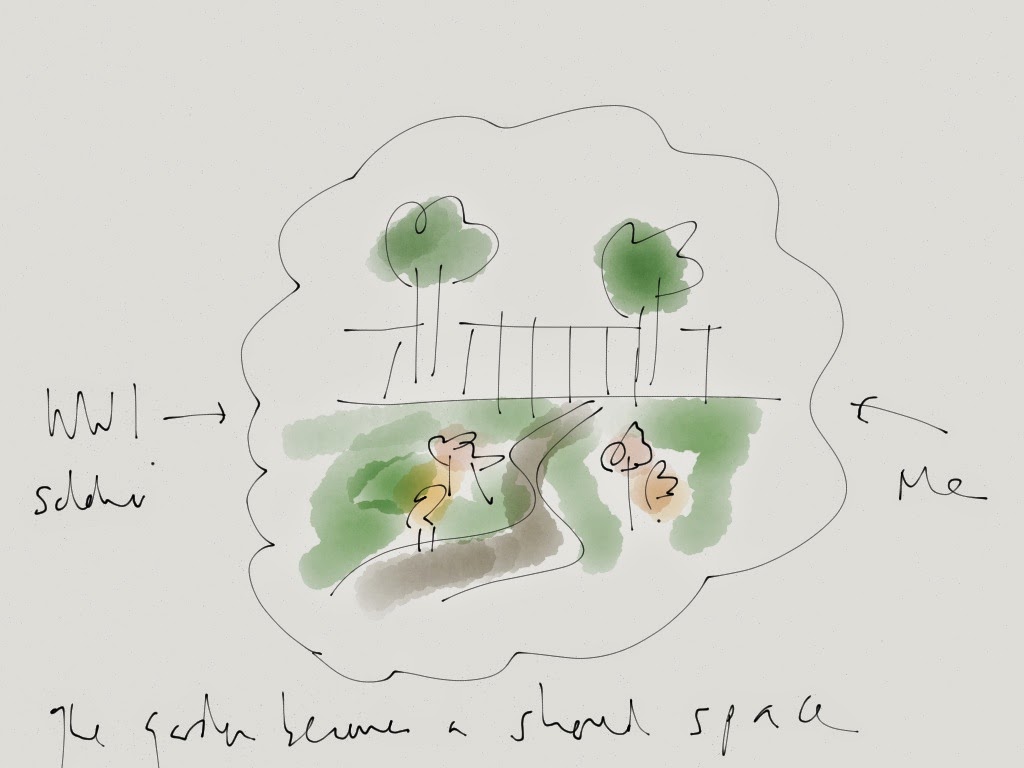

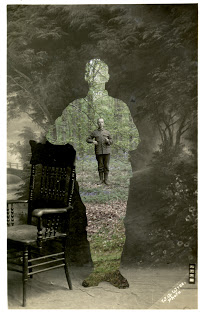

There is a link therefore between a pastoral past, my childhood and the consideration of those who died in World War I as children years before – as real people who existed beyond the theatre of war.

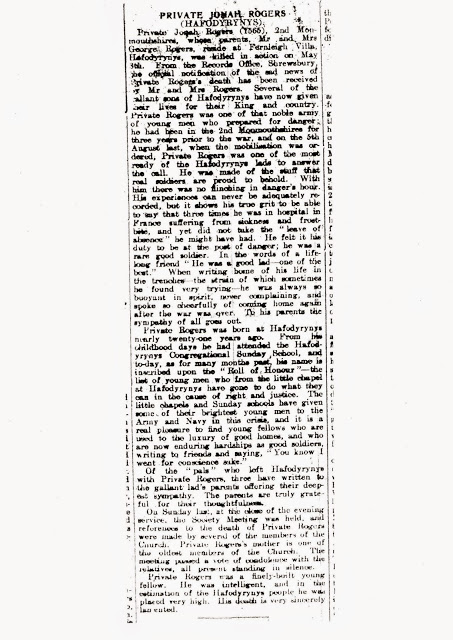

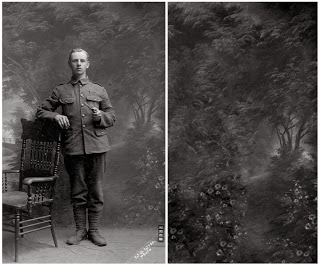

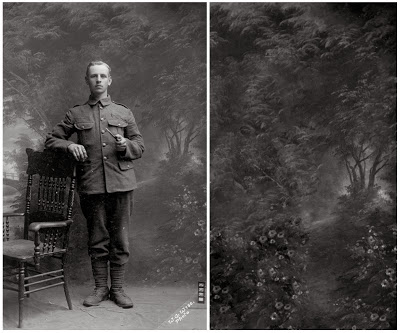

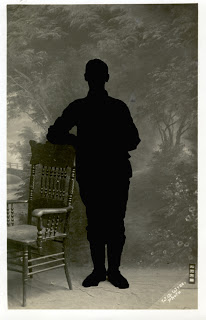

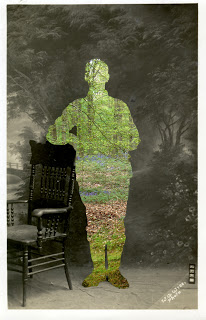

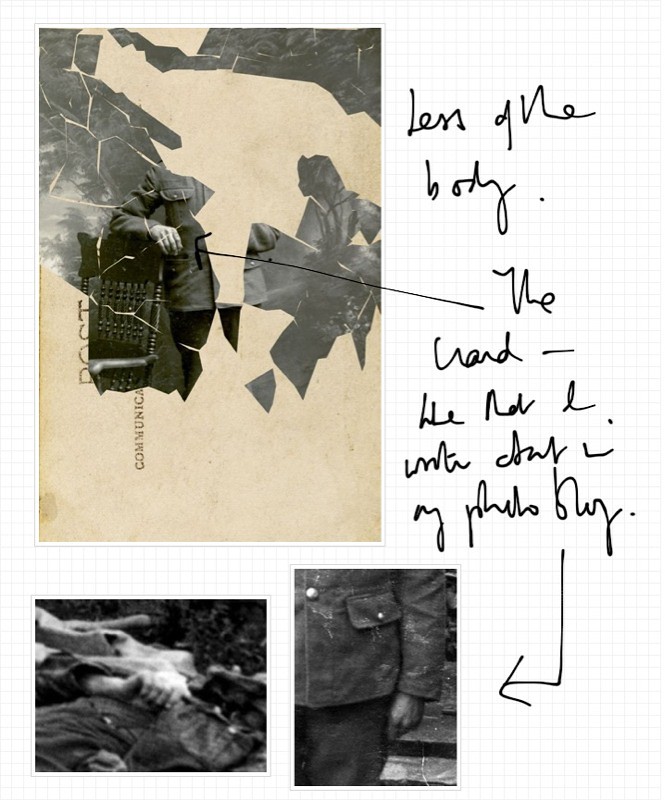

This leads me to postcards, such as the one below:

This postcard shows a soldier posing with his mother(?) standing in what might have been his garden, in the place where, perhaps, he grew up as a child. I might not be able to empathise with him as a soldier directly, but I can well imagine his garden. Part of the landscape of my childhood comprises the gardens of my home and those of my grandparents, as well as parks and playing fields at school. They are pastoral landscapes in miniature, where the grass was cut on a summer’s day.

Proposing moments of pastoral

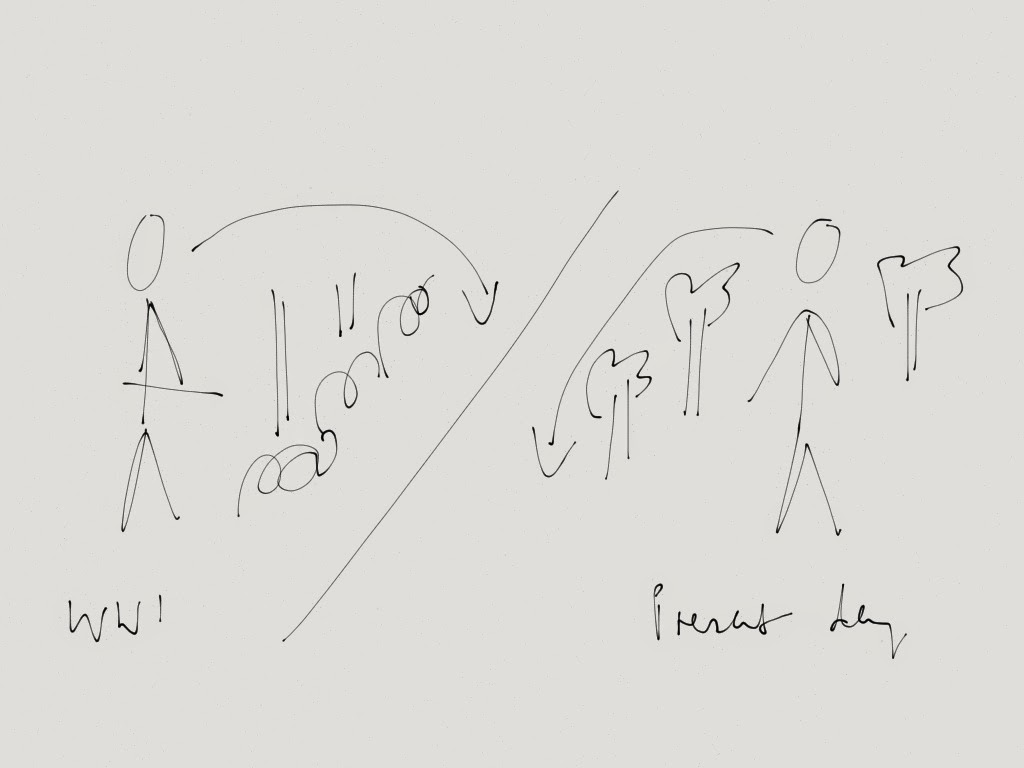

The question which I haven’t asked is: how do you propose moments of pastoral? The answer to this, I think, is crucial to the development of any work.

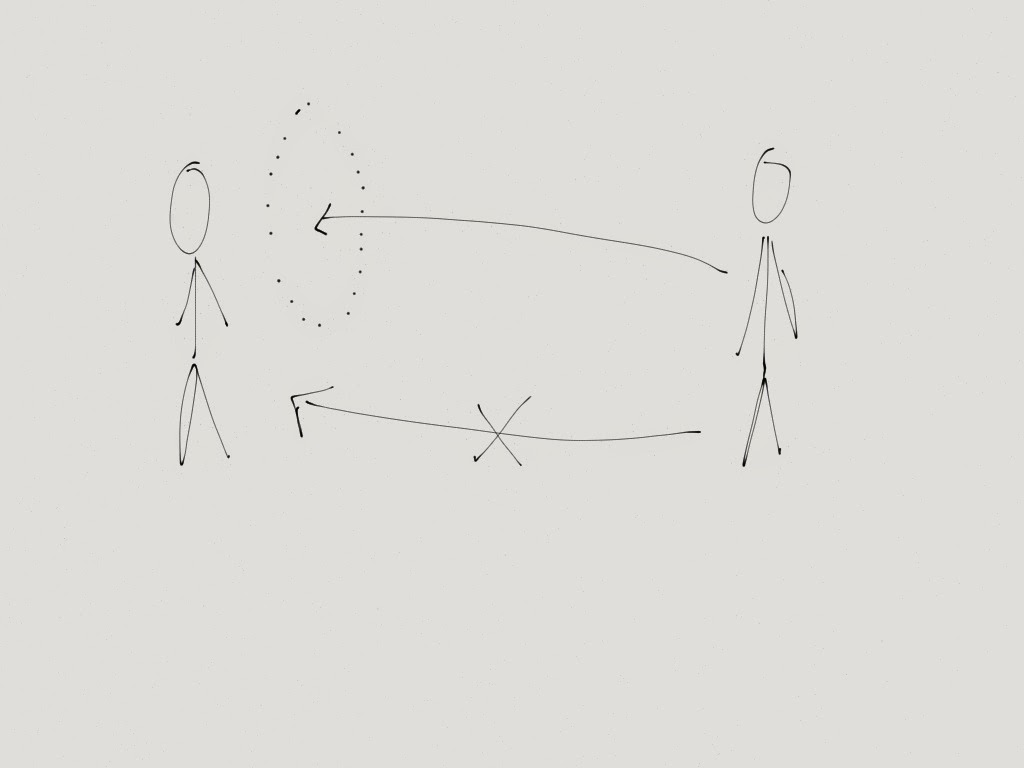

To propose is to suggest, invite. It is something given to another.

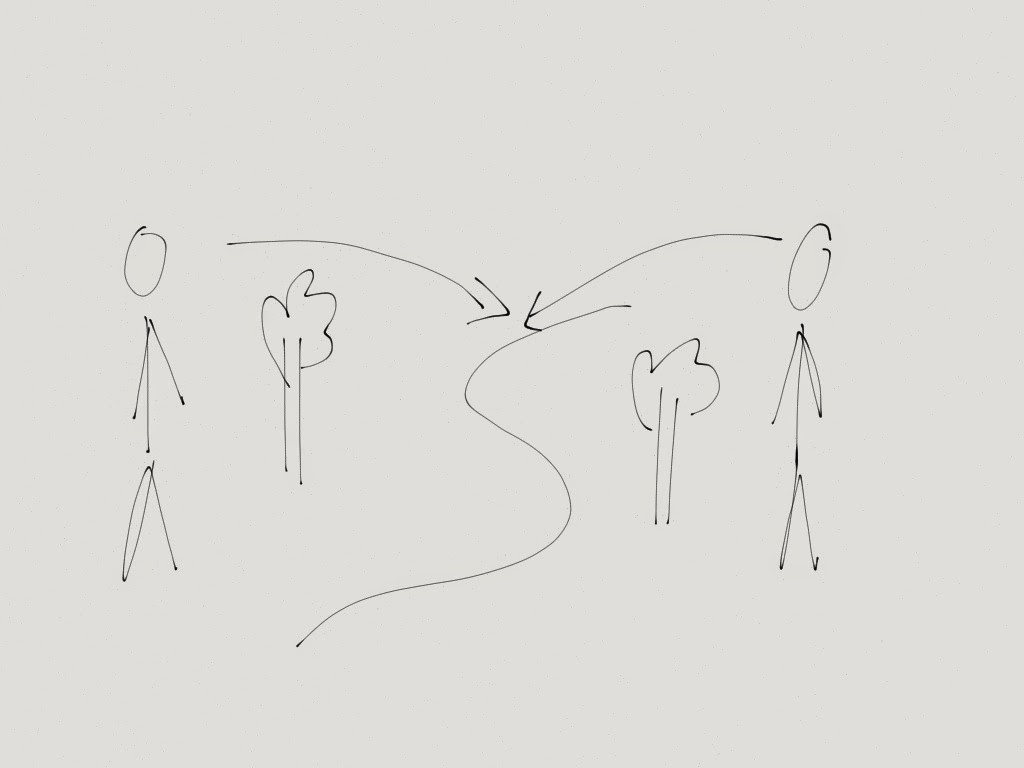

Maps are objects which propose. But what are they proposing? On the one hand, they propose journeys. More often than not, we use them to plan a journey in the future, for example a day trip or holiday. They require us to use our imaginations; to imagine the future, the landscape and our position within in. They can however propose journeys into the past. In a previous blog about Ivor Gurney, I wrote:

After returning from the war, Ivor Gurney, like so many others suffered a breakdown (he’d suffered his first in 1913) and a passage in Macfarlane’s book, which describes the visits to Gurney – within the Dartford asylum – by Helen Thomas, the widow of Edward Thomas is particularly moving. Helen took with her one of her husband’s Ordnance survey maps of Gloucestershire:

“She recalled afterwards that Gurney, on being shown the map, took it at once from her, and spread it out on his bed, in his hot little white-tiled room in the asylum, with the sunlight falling in patterns upon the floor. Then the two of them kneeled together by the bed and traced out, with their fingers, walks that they and Edward had taken in the past.”

The map they laid on the bed was one that showed the familiar trails and paths of the countryside. But it was also one which, like that I made in my childhood, gave Gurney access to his imagination – to his own past. Together, the patient and his visitor read it with their fingers, following the trails as one follows words on a page. A narrative of sorts was revealed, memories stitched together by the threads of roads, paths and trails.

Maps can also be used of course to orient ourselves in the present. We might consult them to find out where we are or where we ought to go. In fact, they can be used to orient ourselves in the past, present and future.

As an artist wishing to propose moments of pastoral, I want to use the form of the map as a starting point. The map might show a pastoral scene, using, for example, the ‘vocabulary’ of the trench map to show the trees.