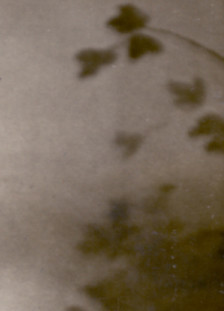

July 1st 2016 will mark the 100th anniversary of the infamous Somme offensive. Having already made a lot of work about World War I, I want to mark this anniversary with some new pieces, working around the theme of ‘shared moments of pastoral’.

There have been numerous starting points which, in no particular order, I will outline below.

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.” Paul Fussell

“Here in the back garden of the trenches it is amazingly beautiful – the mud is dried to a pinky colour and upon the parapet, and through sandbags even, the green grass pushes up and waves in the breeze, while clots of bright dandelions, clover, thistles and twenty other plants flourish luxuriantly, brilliant growths of bright green against the pink earth. Nearly all the better trees have come out, and the birds sing all day in spite of shells and shrapnel…” Paul Nash

‘The next day, the regiment began the long march to the Front. In the heat of early summer, nature had made attempts to reclaim the violated ground and a deceptive air of somnolence lay on the landscape. “The fields over which the scythe has not passed for years are a mass of wild flowers. They bathe the trenches in a hot stream of scent,” “smelling to heaven like incense in the sun.” “Brimstone butterflies and chalk-blues flutter above the dugouts and settle on the green ooze of the shell holes.” “Then a bare field strewn with barbed wire, rusted to a sort of Titian red – out of which a hare came just now and sat up with fear in his eyes and the sun shining red through his ears. Then the trench… piled earth with groundsel and great flaming dandelions and chickweed and pimpernels running riot over it. Decayed sandbags, new sandbags, boards, dropped ammunition, empty tins, corrugated iron, a smell of boots and stagnant water and burnt powder and oil and men, the occasional bang of a rifle and the click of a bolt, the occasional crack of a bullet coming over, or the wailing diminuendo of a ricochet. And over everything, the larks… and on the other side, nothing but a mud wall, with a few dandelions against the sky, until you look over the top or through a periscope and then you see the barbed wire and more barbed wire, and then fields with larks in them, and then barbed wire again.”

As the torrents of machine-gun bullets ripped through the grassy slopes up which the British troops were advancing, the smell of an English summer – fresh cut grass – filled the air. For thousands it would be the last scent they would ever smell.’ Neil Hanson

“There was utter silence, broken only by the twitterings of the swallows darting back and forth.” Filip Muller on the murder of a friend in Auschwitz