Further to my last blog, I have created some more extended backdrops using old, WWI postcards.

Art, Writing and Research

Further to my last blog, I have created some more extended backdrops using old, WWI postcards.

In my work I have always been interested in the past and how we can empathise with those who lived long before us. I like to think about how we access the past and how we build a picture of the long lost world as best as we can. We might start with a fragment of pottery, a detail in an old photograph, a piece of writing, a coin – it could be anything; but we often start with a fragment.

With that fragment, we can then build outwards within our imaginations, trying to experience the world from which the fragment is estranged. We can try to hear it, feel our way around it, see movement as if it’s now and, as I’ve written before, one of the best ways to do that is through the natural landscape. After all, those who lived in the past would have known what it is to walk in the natural world.

We experience a wood in much the same way as someone a hundred, two hundred or five hundred years ago. Yes, their experience would be different in that they would know the natural world differently, but they would see the trees moving in the wind, see the sun make shadows on the ground, see the clouds, the sky, feel the rain and so on. We might not be able to experience a town or city as they would but we can better know a wood as they would have known it.

I have been doing a lot of work in woods lately, painting shadows cast by the leaves of the trees and I like the idea that trees themselves start off as seeds, and that from these small beginnings they grow, reaching out into the world around them. Seeds and trees are therefore a good metaphor for how I try and experience the past. Starting off small and growing up and out to feel my way into a world that no longer exists.

With the shadow work I’ve been doing, the shadows are like the traces of the past – the fragments. With them, we can try and imagine the trees which cast them, building out to picture the sun, the sky, the clouds, birds and all the other trees in the wood.

The wood therefore represents the past; a world in which we might find ourselves walking, experiencing it as best we can like those who lived before us. We start with a seed and planting it within our imaginations, we allow it to grow into another world.

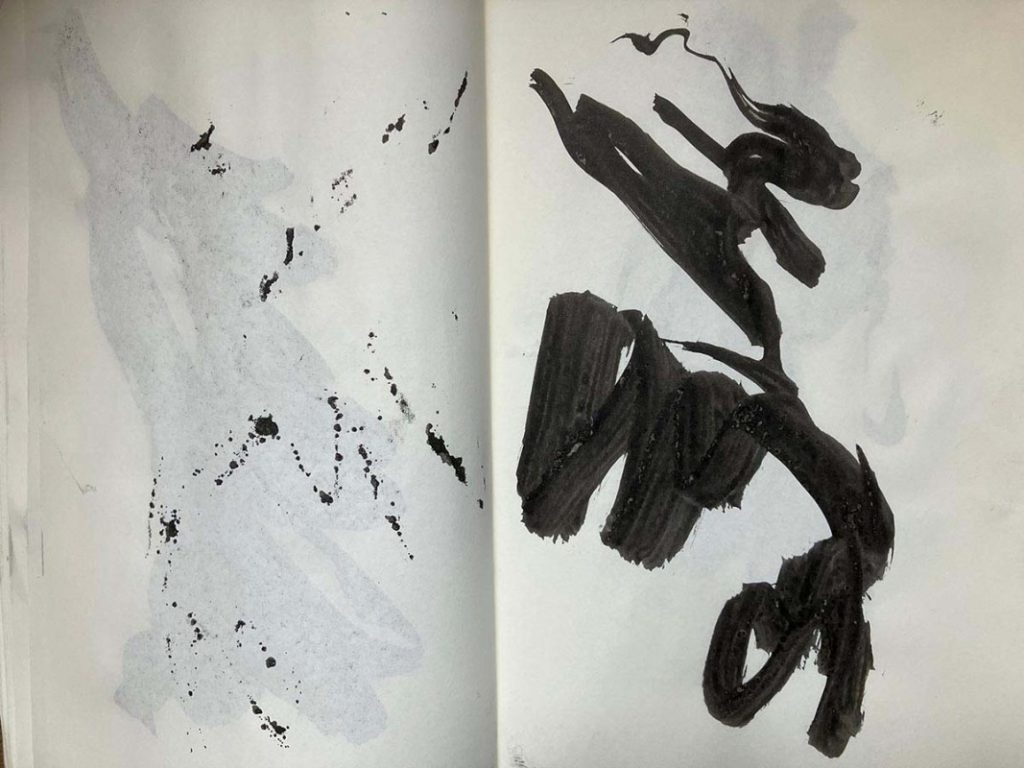

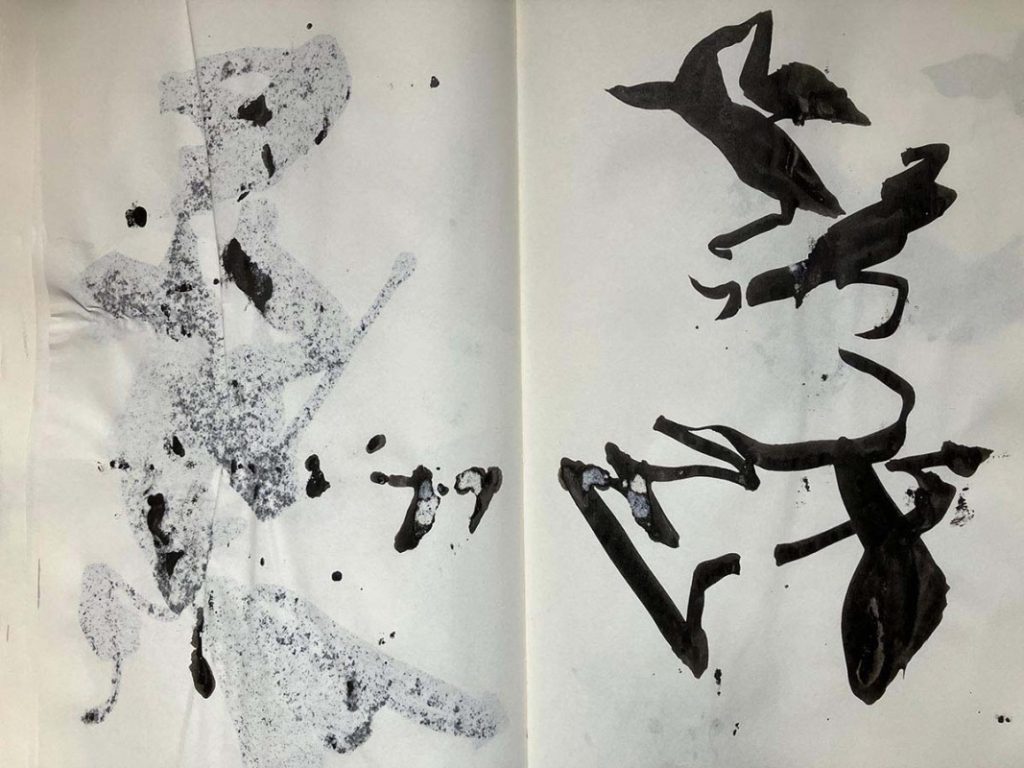

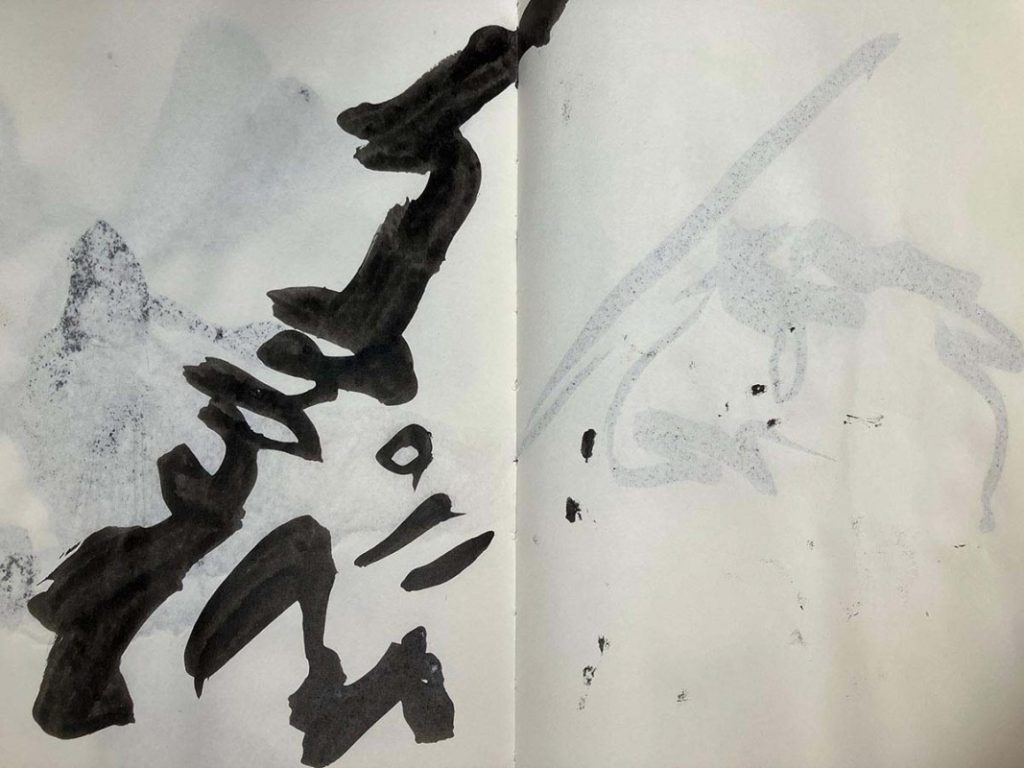

Thinking about I might represent this pictorially, I’ve recently been looking at scrolls and have come up with some ideas of how I might create some work using the format, using the shadow calligraphy I’ve been creating in the woods.

Scrolls are very precise objects – almost ceremonial. They have a form that is both rolled and unrolled and this is something which interests me as regards my work on empathy and the past. The rolled scroll is like our beginning – our fragment, our seed or acorn. It’s like that first bit of knowledge which once untied we begin to unroll. And as we unroll, it’s as if the acorn is growing, reaching out as it begins to build the world of the past.

I love this idea of unrolling. In my Goethean observation, I noted the following in the final phase:

The solidity and tightness of the rolled state – the past hidden.

The untying.

The unrolling and revelation.

The fragility and expanse of the unrolled state – the past revealed.

Then as now.

Delineated.

Breathing.

Defined.

Sounds.

The re-rolling and hiding.

Quiet.

Ceremony and calmness.

Past and present as one.

I can add to that – growing. The scroll is the tree rising up and putting out its branches while putting down its roots into the ground. I like the idea that as the scroll unrolls, it somehow keeps expanding.

One of the things I’ve been looking at is how I can use the scroll’s background. Rather than just using a piece of material, can I use that material as a canvas somehow?

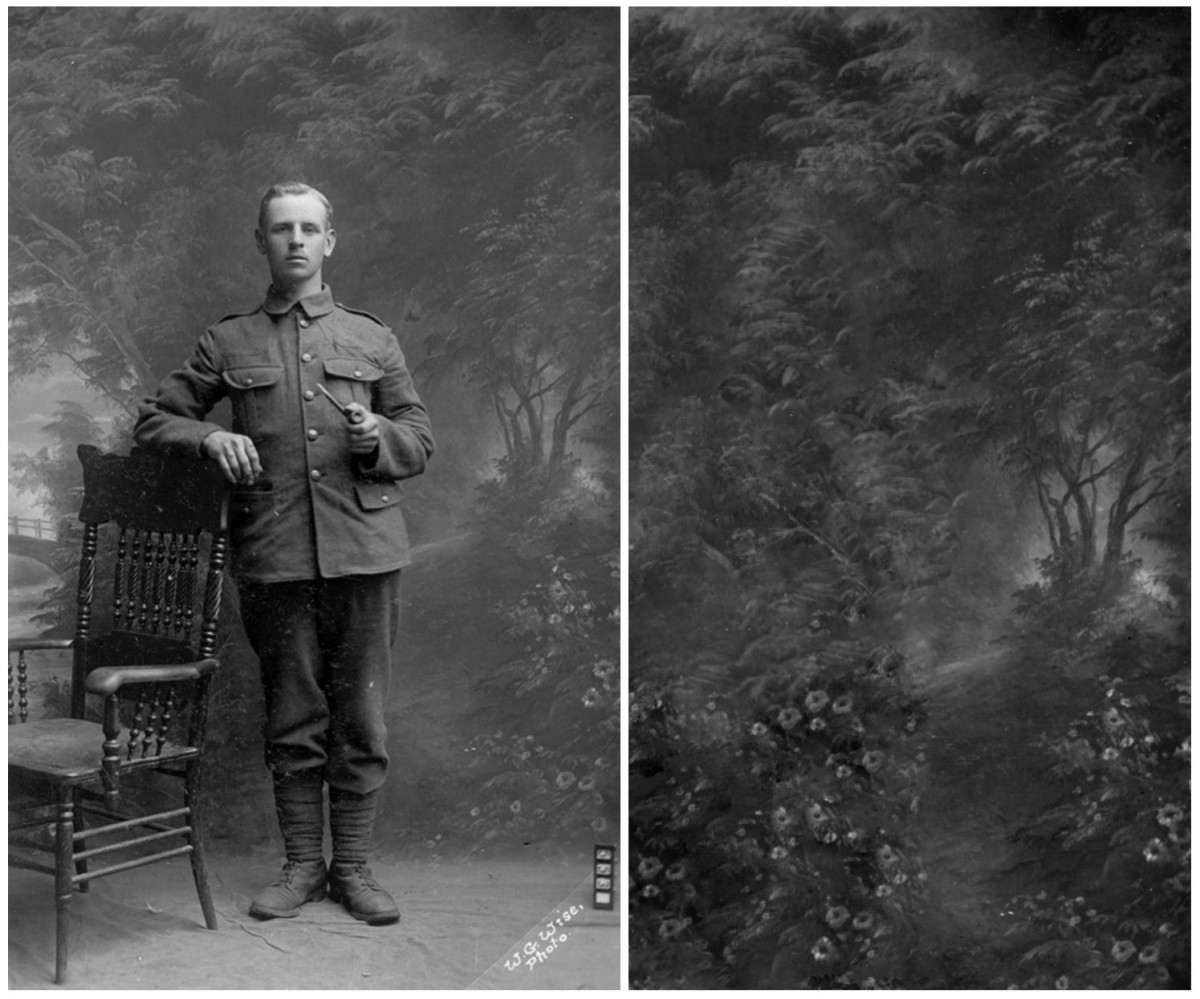

Quite a while ago I was looking at the backdrops used in studio portraits of World War I soldiers (see ‘Backdrops‘, . ‘ WWI Backdrops‘, ‘Backdrops (Odilon Redon)‘, ‘The Past in Pastoral‘) and so I thought that I could use these backdrops as a background for a scroll. The image below is something I did several years ago where I isolated the backdrop in the postcard.

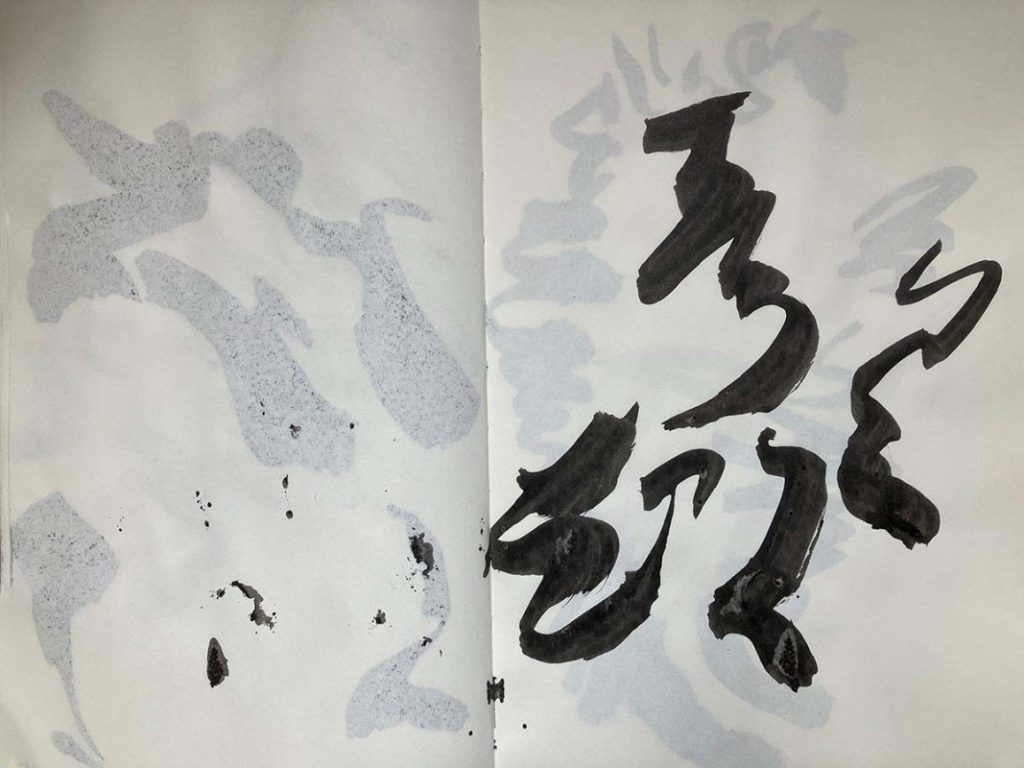

The following is how it might work as a scroll, complete with a character painted in the woods.

The studio backdrop is something in front of which people would have stood to have their picture taken. Those people have long gone and we – or whoever is looking at the scroll – are standing in their place. The painted character is that which I painted in a real wood and represents a moment – ‘now’. When I imagine a past event, I am trying to imagine someone who lived at the time. In a sense, our imaginations are like a theatre where we assemble this moment, complete with backdrop, props, actors and maybe even a script. The idea of the backdrop works very nicely with this.

After completing a recent painting (see below), I wondered whether to add colour as per the initial idea, but I liked the painting as it was and was concerned about spoiling it. The consensus among friends was to leave it as it was – which I did.

Instead, I decided to create some much small works to see how the addition of colour would work and the following small canvases were the result. I do like the addition of colour as it reflects the idea of the mind trying to animate a relic of the past in order to imagine the object as it was in a time long since passed. Looking at the blackened leaves (representing the shadows of the leaves acquiring form) becoming green with the sky behind, I think this process is well articulated. I will now work these up to larger canvases.

We have all lost someone in our lives, whether that’s through death or the breakdown of a relationship. Both are painful and both require us to grieve for the missing loved one. In many ways, the loss of a partner when a relationship ends feels worse; perhaps because the grief has been chosen for us. It fits us like a second skin, but when someone dies, the grief, although painful and also made to measure, is like the remembrance of a close and comforting hug.

I have experienced both these things of late and want to express that grief through my work.

The video below was made a few years back. Filmed in Shotover Wood in Oxford, it shows the shadows cast by trees on a summer’s day and was a way of visualising the idea that all that’s left of the past is like the shadows in the film; that if we want to imagine what the past was really like, we have to imagine the trees, the sky, the sun, the colours and the sounds.

The idea of the everyday within the present moment has always been of interest to me, particularly in regards to how we can empathise with those in the past; particularly those who experienced times of trauma. When I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau in 2006, I was struck by the movement of the trees, aware that those who had suffered so much would have seen exactly what I was seeing. It was something so everyday, but something which had the power to link us together despite the difference in time and of course experience.

“‘…You have no idea how tremendous the world looks when you fall out of a closed, packed freight car! The sky is so high…’

Tadeusz Borowski

‘…and blue…’

‘Exactly, blue, and the trees smell wonderful. The forest – you want to take it in your hand!’”

“Another leap in time, to a different landscape and different colours. The colour is blue: clear blue skies of summer. Silver-coloured toy aeroplanes carrying greetings from distant worlds pass slowly across the azure skies while around them explode what look like white bubbles. The aeroplanes pass by and the skies remain blue and lovely, and far off, far off on that clear summer day, distant blue hills as though not of this world make their presence felt. That was the Auschwitz of that eleven-year-old boy.”

Otto Dov Kulka

“The air, the woods, breathing.”

Adam Czerniakow

The important thing here is how things we experience in the natural world, like trees and the sky, the wind and the rain, can connect us to those in the distant past, because they too would have experienced them. Our lives might be completely different, but those things stay the same.

Back to the trees at Shotover…

I loved the ‘calligraphy’ of the shadows as they wrote themselves on the blank piece of paper on the ground, and used that idea to paint those shadows using ink and calligraphic brushes. It was as if the trees were using me to write. They were like the words of a language created and forgotten in a moment. No-one can read these words; they speak only of a presence – my presence – in the woods at that particular moment.

As I wrote above, if we want to imagine what the past was really like, we have to imagine the trees, the sky, the sun, the colours and the sounds. So having transferred these ‘characters’ to canvas, I began to paint, adding colour, as if, with the video, trying to imagine the fullness of the moment from which they were taken.

So where does this with my own feelings of grief?

Grief is an expression of our relationship to someone’s absence. Its language is written in shadows like the patterns cast by the trees. But these shadows are cast by the memory of our loved one. Remembering the colours, the sounds and how it felt is painful. But remember them we must – and without regret.

Holding on to regret is like clutching feelings of anger. Soon they will start to eat away at us, damage us. We have to let them go by transforming them, just as we can try and transform our own suffering.

To transform our suffering we must ground ourselves in the present moment. When a relationship ends, it’s all too easy to become entangled in our thoughts, trying to make sense of the other person’s actions. I found myself doing just that for days and days, walking round in circles, going nowhere except down. And what would it achieve anyway? Trying to work out why something happened won’t change the fact that it did happen.

All I could learn to do was be as present in the moment as I could, to let go of my thinking about the past. That’s not to say I had to try and forget her; the memories of our time together would always be with me and precious with it. But when I think of those memories, I’m not trying to understand them or change them. I just had to stop striving for answers which I’d no chance of knowing, as if knowing them would somehow change the outcome and alleviate the pain.

I still walk and I still think, but walking meditation, where one is grounded step by step in the moment, helps still the mind and cultivate a sense of peace. Looking at the trees, the clouds, the sky. Feeling the wind or the rain (or both) helps me find the peace and contentment within. It helps my mind reconnect with my body just as I can try and connect with those who lived generations before us.

First painting I’ve finished in a long while. I called this one ‘Nana’s Mountain’, after the hill behind her garden, up which she used to watch her dad walk on his way to the mines.

Since buying the piece of Roman glass I described in my previous post, I’ve been interested in its iridescent surface and what causes it.

Having done a quick search I discovered the following on an ancient glass website:

Caused by weathering on the surface, the iridescence… is due to the refraction of light by thin layers of weathered glass. How much a glass object weathers depends mainly on burial conditions and to a lesser extent the chemistry of it… The word iridescence comes from Iris, the Greek Goddess of rainbows and refers to rainbow-like colours seen on the glass which change in different lighting. It is simply caused by alkali (soluble salt) being leached from the glass by slightly acidic water and then forming fine layers that eventually separate slightly or flake off causing a prism effect on light bouncing off and passing through the surface which reflects light differently, resulting in an iridescent appearance.

On another website:

Water leaches the alkali (soda) from the surface of the glass, especially in slightly acidic burial environments. This leaves behind fine layers of silica that can flake off the surface. The iridescence is purely a visual effect; in the same way that water droplets in the air cause rainbows, light is bent and split into its separate colours as it passes through the thin layers of deteriorated glass and air.

Having read the above, I decided to view the glass through a microscope, the rather beautiful results of which can be found below:

In these images you can see the fine, flaking layers and how they refract the light to create the iridescence visible on the glass.

Following on from the shadow work I’ve been doing I decided to work in some colour. I suppose it would signify the idea that our concept of the near past is often framed by the black and white media of its production, whether that’s in its photography or film. Then there are the texts written about the more distant past, whether contemporary or otherwise which, in our minds, become a blend of forms and colours as we try to picture that which they describe.

There was a moment several years ago when I found a piece of mediaeval pottery on a dig in Oxford. From out of the dark brown earth, the vivid yellow of the shard was made visible for the first time in several hundred years; seen for the first time in that great span of time. In some ways it was quite unsettling as I described in a blog in 2014.

The introduction of colour changes these ‘shadow texts’ into something else; a remembrance of things we could never have known, the memory of which we can only imagine.

Having recently bought and iPad Pro and pencil, I decided to start drawing in a style inspired to some extent by my son’s drawings and by my recent visit to Shotover wood, and, I have to say, I was pleased with the results.

The process of drawing without too much consideration of what one’s aiming to represent is similar to the process of automatic writing, where the subconscious drives the pen. I did something like this 10 years ago after a visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau, a trip which inspired much of the work I made over the next 2 years as I completed my MA in Contemporary Arts at Oxford Brookes University. Two of the pieces that came about after various ‘automatic’ strategies are those below. First a series of drawings…

and then a series of text works…

The title of this post – ‘Somewhere Between Writing and Trees’ – is to some extent a reflection of an ‘automatic’, ‘subconscious’ process and the conscious drive to a representation of trees. Trees have played an important part in my research over the past ten years and after a gap in my work of late, they are I’m sure, a means of finding my way back in, particularly when coupled with thoughts of my son. Separated from my wife, I am also separated from both my children for much of the week, a pain which, anyone in my position would empathise with. Empathy itself has been an important part of my research – in particular regarding the victims of the Holocaust and the millions who died in World War I – and trees have played a part in bridging the gap between the past and present – a necessary step towards empathy. With regards to the Holocaust, it was the way the trees moved at Birkenau which closed a gap of almost 70 years; with World War I it was a quote from Paul Fussell: “…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

We are familiar with the image of blasted trees from the battlefields of The Somme, Ypres and Verdun, but nothing in our imaginations can take us there. We can never experience what those men had to endure, day after day, night after night. So the idea of looking for the pastoral as a means of empathising with victims of war is an important one, helping to bridge the gap by reminding us how these soldiers were ordinary men before they enlisted; men who were once boys, some of whom no doubt played in woods and climbed trees.

When I was a boy I was obsessed with woods and forests. Trees were a means of escaping the present, where in the early 1980s, the threat of nuclear conflict was ever present. They were a means of escaping to the past. I loved the idea of the mediaeval landscape, covered with vast swathes of trees, because, quite simply, it was a place where nuclear weapons did not exist. Of course it was an idealised past; an overly pastoral one, and to some extent the backdrops of portraits made of soldiers before they went to war remind me of this place. The following is a piece I made based on those backdrops.

Every one of these men was someone’s son which brings me back to my own, to his drawings and my drawings of trees.

Drawing and drawing with my son, helps close the gap which separates us for much of the week. It helps me feel close to him when he isn’t there. Drawing trees is a process which takes me back to my work, and whilst thinking of my son, becomes another means of empathising with those in the past.

Following on from previous posts about my son’s drawings and photographs taken at Shotover, I’ve been drawing ‘trees’ (or at least, using them as a starting point), whilst trying not to be too conscious about my approach. The results are as follows:

As I was drawing them, I was reminded of drawings I made years ago as part of an observation I made of an apple tree growing in my mum’s garden.

In a previous blog (Imagination and Memory) I wrote the following:

“Going back to my childhood, my imagination provided me with a means of escape (not that I needed to escape anywhere – I was fortunate enough to have the perfect upbringing). I’d always wanted to see the world unspoilt, an Arcadian vision without cars, planes, pollution, machines or any trace of the modern. And in a sense, this is I believe, what first fired my interest in the past.”

This is one of the maps in question, photographed in my bedroom around 1983.

Thinking again about ‘a means of escape’, I realised that despite what I’d written, there was a ‘need’ to escape somewhere. Throughout the 1980s the Cold War was at its height and although recollections of the period bring back many happy memories, there was always, simmering in the background, the anxiety of a nuclear conflagration. Every time a ‘crisis’ was reported on the news, my dreams at the time would always be the same: I’d watch from my garden as a huge mushroom cloud billowed up above the horizon. And in the days before 24 hour rolling news, the refrain “we interrupt this programme to bring you a newsflash” would stop my heart.

The worlds that I created were places where, quite simply, there were no nuclear weapons, and therefore no risk of nuclear war, but just as these imaginary places offered a means of escape, so did history – in particular pre-industrial history and to bring the past to life, for example the mediaeval world which was especially compelling, I had to use – just as I do now – my imagination. In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes writes:

“Imagination and memory are but one thing, which for divers consideration hath divers names.”

One could perhaps say the same about history. Certainly in my mind, those three things – history, memory and imagination – were conflated, creating a landscape in which I could wander at my leisure; a place to which I could escape. And it was through the creation of maps that I found my way there.

I am looking at a shoe made of leather which is on display in a glass case in the Museum of Oxford. With it on display are a number of other leather artefacts, but I will reserve my observations for the shoe in question.

The shoe, which I believe is that for a right foot, is dark grey in colour. It rises above the ankle, it’s quite small but appears to be one that would have belonged to a man. It has a small round metal buckle which appears to be the only fastening. It’s a little worn at the edges, particularly at the front, but not so worn on the back; it’s more or less intact. The upper part of the shoe has been cut in six places. The cuts have been made on the right hand side and the last cut which is more of a hole has been cut into the top of the shoe. The buckle is also on the right hand side. It’s round with a metal part on the inside such as one would find on a belt buckle. Opposite this, on the left hand side is a small hole which I assume is the fastening. Looking at the buckle, and the small metal part inside, I assume that there was a strap which passed through the buckle and around the shoe.

Looking into one of the cuts made in the right hand side of the shoe I can see three small holes in the bottom at the edge. The shoe is about 8 to 9 inches in length, the back of the shoe rises approximately 4 or 5 inches. The shoe is behind glass so obviously I cannot touch it.

The sixth hole cut into the top of the shoe has a cut in each of its edges, as if the hole was made first by cutting two crossed lines into the leather and then making the hole from these. The first cut in the shoe, that nearest the sole, is about 2 inches in length, the second about an inch, the third and fourth slightly smaller, the fifth about half an inch long. The hole is about ¾ inch in diameter.

The shoe has been packed inside for display with a white material. Looking at the back right hand side of the shoe (just behind the ankle) I can see that it has been cut, but it seems to be part of the shoe’s design, to ease the task of putting it on. The shoe has also been cut down the centre, again part of the design, to about two inches from the buckle. The sixth cut – the hole – is about an inch and a half from the end of this cut.

The right hand side of the shoe is that which is most visible and I can clearly see the texture of the leather, I can almost see the shape of the heel where the shoe has moulded to the shape of the wearer’s foot. There is a large crease just above where the ankle would be (which seems to correspond with the idea that the shoe would have been fastened with a strap). There is another large crease running down from the buckle towards the sole.

Part 2

What is clearly seen in this shoe is the apparent simplicity of its construction. I can almost see it as a single piece of leather and as I consider this I begin to picture it in the hands of the tanner. I can almost see the carcass of the animal from which it was taken (I wonder for a moment about the cow; where had it grazed, when was it killed), the man who cut it and prepared the leather. I can hear the noise of the place in which he worked and see this piece of leather as the means by which he is able to live. I assume he knows the shoemaker? Did the shoemaker live in the town? Did the tanner? What things were on his mind as he worked the leather in the 13th or 14th century? And what about the buckles, where were they made? Who made them? Were they sent to the shoemaker along with other buckles? What was going through the mind of the man who made it? What was happening in the world when it was made? The same question applies to the tanning of the leather and the making of the shoe itself.

At some point the leather from the tanner and the buckles (from the ironmonger?) would have found their way to the shoemaker. Did he work alone? Were there others working with him? Were the shoes bespoke, made to fit individual buyers, or did he just make them in bulk? Did he know the man who wore this shoe? If he did, what did he talk with him about as he measured up his feet? What was happening in the city at the time, how long had it been since the tanner had sent the leather? What was the process of making the shoe, how long did it take? What was the buyer wearing on his feet as he talked with the shoemaker? Did the buyer select the leather or was it just whatever was available? Why did the buyer chose this particular design? What were the shoes for – everyday use? What was the shoemaker’s workshop like? What were the sounds both inside and outside?

Having talked with the buyer, the shoe maker would begin to mark the leather. What did he use? A piece of chalk? He would cut the leather to shape, making the cuts that I could see in the shoe – those that were intentionally part of the design. And then, having cut the pieces, he would begin to sew the shoe together. Did he do it in the light or in the dark, under the light of a candle? What did he think about as he worked the needle and thread? Was he an old man. Did the drawing of the thread help him in his thoughts? What were the sounds as he worked? Quiet, except for the noise coming from the street. As I see him work, I begin to feel the rhythm of his body, I feel his aches and pains. I feel the squint of his eyes as he tries to see more clearly what he is doing.

Did he like the man for whom he made the shoes? When he finished the shoe, did he pick it up and look at it admiringly, squinting again to make sure everything was perfect? It had to be, this after all was how he made his living.

The final touch, the attaching of the buckle. The shoes were ready to be collected. The buyer comes and picks up his shoes. He enters the workshop (perhaps the shoemaker delivered them to his house?). What time of year is it? Winter? Is it cold outside beyond the warmth of the workshop? One can hear the sounds of the outside pour in through the door along with the chill. Or maybe it’s summer? Is the workshop warm, stifling? The man is eager to try on the new shoes. He takes off his old ones and takes the new pair from the shoemaker (what do they feel like, what colour are they?) Do they carry on their conversation from last time, or do they just make small talk? The man tries them on, they fit perfectly. He walks in them for the first time, up and down the workshop. The shoemaker smiles and waits for the money. How much did they cost?

The man takes the shoes. Does he wear them out, does he discard the old shoes he’s been making do with for so long? Where does he go when he leaves? What does he do, what is he thinking about? Does he speak to anyone? What does he see as he walks in them for the first time along the streets he knows so well? Over time the shoes – the leather – begin to soften and fit themselves to the shape of his feet. His walking makes the creases and folds in the leather. They fit better and better but there is a problem with his right foot. He has bunions which are making walking painful and difficult. But there’s little he can do about it except walk as best he can, his grimacing face showing the signs of his discomfort. Do people ask if he’s okay as he limps down the street, or is it a common sight in mediaeval times?

Where does he wear the shoes? Which streets did he walk down whilst wearing them? Inside which buildings?

The pain gets worse and in the end it’s all he can do, in a moment of desperation to take a knife and cut two lines in the shape of a cross in the top of his shoe directly above the bunion. Did he start by making the one cut and proceeding to cut more as the condition of his feet deteriorated, adding the cuts on the side? Or were they all cut at the same time? What went through his mind as made the cuts? How old were the shoes when he had to cut them? Was it just the one shoe that was cut this way?

As time goes by, the shoe is discarded (what about the other?). Perhaps the man’s condition became so bad the shoe no longer fit him. Perhaps he died? Where was it thrown away? Somewhere wet, somewhere that kept them so well preserved. The moat of the castle? The river? Who threw them in? The man himself – or perhaps his wife? Maybe someone else. Did they think of the man when they threw them away? What happened to the shoe after it was discarded. Did it float on the surface of the water? Was it dark when they were discarded? Was it light? What could be seen, what could be heard the moment the shoes hit the water’s surface?

Part 3

The ground.

The air.

Pressure. Weight. Weightlessness.

Something lives within, then is gone.

The space left behind; the imprint of weight and weightlessness combined.

The wet. The mud.

Soft. Hard

Heat. Dust. Scratching. Expanding.

Held together, seams, thread, pressure.

Stained by the long dark. Sudden break. Noise and light.

Empty. Fixed in shape by the memory of something living.

Long gone to the ground.

Part 4

I am made of many parts, there are different aspects of my being, the leather, the threads, the holes, the emptiness inside. The absence of the body (the foot) around which I was pulled tight, which moulded my shape. I moved, I expanded as I felt the pressure above and below me. I was squeezed between the two or sometimes left in the limbo of lightness. I breathed. I took in water, I dried out. I absorbed smells and over time my smell changed from that of the shop in which I was made to the smell of the house in which I was sometimes left. I was the smell of the man who wore me and the smell of the streets of which I was a part; the streets left behind with versions of myself; depressions left in the ground. I felt pressure outside and within but now I feel nothing, just a limbo of lightness. I smell of nothing. The pressure of the mud which encased me, the darkness, the shape in which I was fixed for centuries. I was beneath the ground the shape only of myself, of one of those depressions left in the street. Long, long dark. Silence. Then light, sudden light and noise and careful hands. Not like the hands of the man who owned me, but the hands of the man who made me, the careful hands of the shoemaker who cut me into shape, who carefully punctured the holes for the thread, who looked at me with great satisfaction. Now that same look is extended to me once again and I am light, and in the light. I have come an impossible distance, but am in the place where I have always been. Where is the other shoe? Where are all the other shoes made by the shoemaker, made by all the shoemakers?

Gesture

One of the ways I use this Goethean method of observing is by using it has a framework on which to hang a series of questions (Phase 2). I find this a good way of trying to understand what the shoe might have experienced over the course of its ‘lifetime’ by trying to locate its changing place within a mutable, physical world. It’s also worth, once I have finished writing, going back over what one has written so as to try and tease out the ‘essential’ elements of what has been observed; these elements can then be used to try and locate the ‘gesture’ of the thing.

What I notice when reading over the text is how the shoe is often positioned at various thresholds. A number of words seem to suggest this:

Ground

Air

Weight

Weightlessness

Thread

Pressure

Filled

Empty

(Hollow)

Memory

(Forgetting)

There is also the fact that the shoe exists at the threshold between the animate and the inanimate, between man and object. “As I see him work, I begin to feel the rhythm of his body, I feel his aches and pains. I feel the squint of his eyes as he tries to see more clearly what he is doing.” Of course it maybe that he felt no pain and didn’t squint, but nevertheless, what one can find distilled in the fabric of the shoe is the rhythm of the maker’s own body, as well as of course, that of the man who prepared the leather, the buckle and last but not least the wearer.

There is also a threshold which is a little more difficult to explain; that between conscious thought and unconscious doing. For example, one can imagine the shoemaker making the shoe almost unconsciously, as if he has done it so many times before, the action is almost a part of his being like walking. But coupled with that is what he was thinking whilst unconsciously ‘doing’. Nothing works in isolation and I like to think that whatever he was thinking somehow – no matter how perceptibly or imperceptibly – translated itself in whatever way, into his actions – in this case making the shoe.

The shoe therefore exists at these thresholds too; between the inanimate and animate, conscious thought and unconscious doing, and, it could be said conscious doing and unconscious thought.

Thinking further about these thresholds, I began to see the shoe as a kind of spring, one which over a period of time is more and come compressed from both the weight of the wearer and the pressure of the ground on which he walks. Looking at the shoe today, one can almost imagine it, as a spring, unwinding like a clock, telling a time that to us at least barely changes at all.

Turning then to the shoes in Majdanek, one can imagine them all this way, as springs which are slowly unwinding. In this sense, the mountain of shoes is imperceptibly moving, exerting by degrees an influence upon its surroundings.

Just as a body lying buried in the ground continues to exert an influence upon its surroundings, so does every shoe, and I can’t help but imagine, that this uncoiling inside each one is the slow release of a long unbroken memory, of the human who wore them and the pathways which they walked.

Species of Spaces and Other Pieces – Georges Perec

Memory, History, Forgetting – Paul Ricoeur

Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory (Cultural Memory in the Present) – Andreas Huyssen

Family Secrets: Acts of Memory and Imagination – Annette Kuhn

The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World – David Abram

White Magic and Other Poems – Krzysztof Baczynski

The Art of Memory – Frances A. Yates

The Poetics of Space – Gaston Bachelard

Shadows and Enlightenment – Michael Baxandall

A Short History of the Shadow – Victor I. Stoichita

In Praise of Shadows – Jun’ichiro Tanizaki

After thinking about it for quite some time I have finally made some changes to my website. Since starting my MA in Composition and Sonic Art at Brookes University here in Oxford, I have come to the realisation that for too long I have been restricting my artistic practice by compartmentalising everything I do. So, whereas before on my website I had categories for art, music and writing, I have chosen instead to see these disciplines as more a means to an end rather than an end in themselves. So, from now on, everything I do will come under the singular term ‘art’, even though ‘art’ is not in itself a category on this website; I am an artist rather than an artist, writer and musician.

On the MA, we have been encouraged to explore different strategies for creating artworks, and for exploring ideas. I have been guilty in the past – like so many others – of having an idea and instantly thinking of the end result; designating a medium and visualising a form before I’ve even explored the idea or theme. Working this way has always blocked me, for, rather than thinking about the meaning behind the work, I have instead always thought about the work – or what I have perceived the work will be. For example, I think of an idea, and say to myself, “I will do a 10 minute video piece…” and at once the idea is constrained, strait-jacketed, and, as a result it withers and dies; crushed, more often than not, by concerns over technical constraints (and possibilities).

So, this website marks a departure from that way of working. Now with my ideas, I try and look for a way in using strategies such as free-writing, drawing (as a means of understanding a given thing) and mapping. However, in designing the website, I still required categories of sorts and decided upon three; not Art, Writing and Music as I had before, but rather Places, People and Objects.

Much of my work is centred around the concept of place and deals in particular with memories of that place. These works might – eventually – be video-based, sonic, aural, text-based, paintings, drawings… whatever, but I have refrained fromusing any of these as categories in themselves. Instead, under each heading I have listed the various projects I am working on and within each of these have created six headings, those being; Introduction, Context, Evidence, Approach, Journal and Progression. More may follow, but as things stand these will suffice.

Introduction is just that, an introduction to the themes and ideas which I am exploring. Context is an explanation of my reasons for wishing to pursue the idea; how the Place, Person or Object relates to me and vice-versa. Evidence is an exploration of the thing’s background; it’s history, it’s place in the past, the present and – in conjecture – the future, as well as being a collection of relevant readings and/or images. Approach is a summary of the methods I have used – or am using – to explore the idea or theme, for example, free-writing, drawing or mapping. Journal comprises extracts of my journals and sketchbooks and Progression is a look at work carried out thus far, with thoughts on possible final pieces.

As said, this way of working – and indeed thinking – marks a departure for me, but already I have reaped the rewards. Hopefully, you, whoever you are, might reap some reward too.