Continuing with my research, I’ve gone back a few years to some work I did on World War I, specifically an ‘observation’ made of a trench map and graphite paintings using that map as a basis for the work.

I’ve always liked the idea of using the map format as it articulates both the idea of place and of someone in that place. Combining it therefore with the recent work I’ve been doing on fabric tokens works well; the token describes an absence (and also, in some respect, a presence in that it’s a fragment of a lived life), while the map onto which it’s pinned articulates the space beyond that fragment. As I’ve written before:

“Every object in a museum, every relic (whether an object or building, or part of a building) is surrounded by space; that time and space from which they are now estranged. The fabric tokens in the Foundling Museum are likewise surrounded by space, into which the patterns seem to seep.”

The token, the seeping pattern and the map all combine therefore to articulate the ideas I’ve been working with over the years.

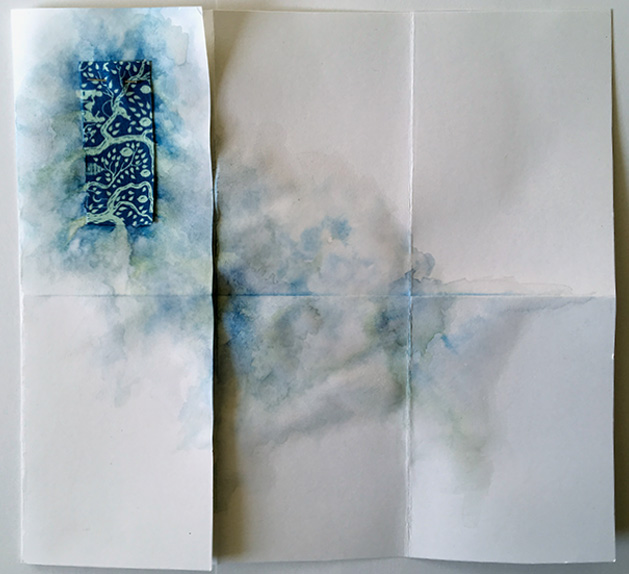

Using some folded paper, I made a sketch…

There is something about this pattern and the seeping image which somehow refers to childhood. Therefore I’ve decided to work this up into a bigger piece called ‘Raspberry’, named after a girl, Raspberry Hovel, who lived at the start of the 19th century and who I discovered in my family history research.

This image also reminds me of mediaeval manuscripts (the token being the drop-cap) and in some respects, the blankness surrounding the text is like the space I’ve described above. I’m always fascinated by annotations and marginalia in such works as they serve to bring us face to face with those who read those books hundreds of years ago. The seeping pattern becomes in a way a kind of marginalia.

Taking this further, I’m reminded of an installation I made in 2008/09 called ‘The Woods, Breathing.‘ This was based on my reading a book which Adam Czerniakow had read during the dark years of the Holocaust. A text work I made called ‘Heavy Water Sleep‘, based on that book, also lends itself perfectly to this form.