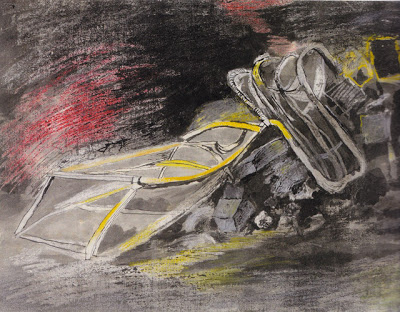

‘Ghastly by day, ghostly by night, the rottenest place on the Somme’. Such was how soldiers described High Wood, one of the many that peppered the battlefields of Flanders and France. Woods in name only, these once dense places were quickly reduced to matchwood. One officer, writing of Sanctuary Wood near Ypres, declared that: ‘Dante in his wildest imaginings never conceived the like.’

We, in our wildest imaginations can not conceive the like. So how can we remember and empathise with those who for whom it was real? Historian Paul Fussell provides a starting point:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

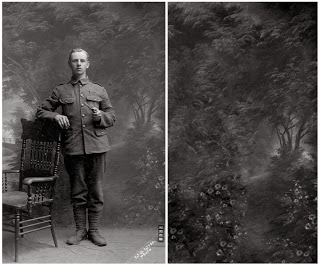

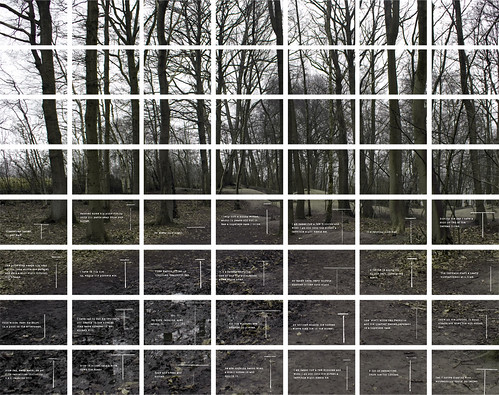

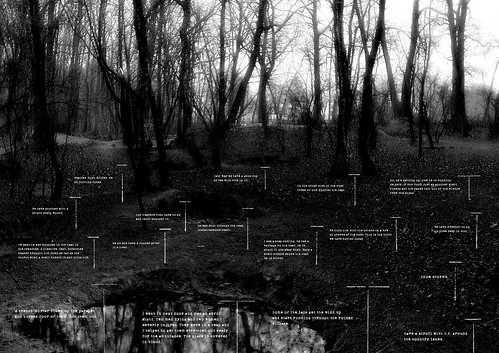

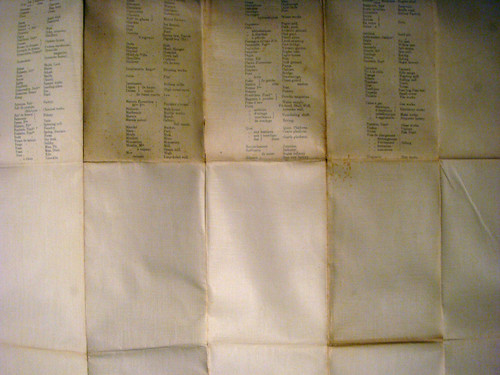

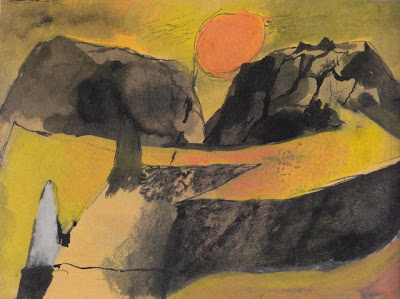

I aim therefore to create a series of pastoral landscapes and accompanying maps which use, as their starting point, portrait postcards of Great War soldiers (in particular, elements found on the studio backdrops against which they were photographed) and Trench maps. Although the pastoral scenes will be empty – devoid of human life – I aim nonetheless to create a sense that people have been there; that the landscape is remembering them – an absence rather than a lack. This will serve to articulate the journeys of those soldiers, from photographic studio to the Front, and for many, death.

Two quotes are useful here; the first from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies:

“Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.”

The other from Wordsworth’s Guide to the District of the Lakes:

“…we can only imagine ‘the primeval woods shedding and renewing their leaves with no human eye to notice or human heart to regret or welcome the change.'”

In Rilke’s poem, the idea of trees (among other things) remembering through their silence those who’ve passed amongst them is particularly appealing and finds a kind of reversed echo in Wordworth’s imaginings of the primeval woods: where it isn’t the human heart regretting or welcoming the change, rather the trees, regretting (or welcoming) our absence.

Words from war poet Edward Thomas serve to further this idea of ‘remembering trees’. In the Rose Acre Papers, a collection of essays published in 1904 he writes:

“…a bleak day in February, when the trees moan as if they cover a tomb, the tomb of the voices, the thrones and dominations, of summer past.”

His widow, Helen, writing after the war in ‘World Without End,’ described how the “snow still lay deep under the forest trees, which tortured by the merciless wind moaned and swayed as if in exhausted agony.’

It’s almost the same lamenting her husband had described before the war.

Richard Hayman, writing in ‘Trees – Woodlands and Western Civilization’ states that “woods are poised between reality and imagination…” As a child woods were, for me, a means of accessing both my imagination and the distant past; a place “for chance encounters” with historical figures, monsters and knights. Woods, as Hayman puts it, are places which can “take protagonists from their everyday lives” while, as I would add, keeping them grounded in the reality of the present.

As a child I would often create maps of imagined landscapes covered – like my imagined mediaeval world – by vast swathes of forest. And as an adult, the act of drawing them returns me to a place where my childhood and the distant past coexist; “a mixture of personal memory and cultivated myth” grounded in the nowness of the present. As such, the ‘pastoral’ landscapes I’m going to paint, based on those strange and incongruous studio backdrops, become too, landscapes of childish sylvan fancies.

When considering the war, much of our attention is, naturally, focused through the lens of its duration: the years 1914-1918. But every one of those men who fought in the trenches was once a child, and since becoming a father this has become an important aspect of my ability to empathise. To empathise, we must see these men unencumbered by the hindsight which history affords us; as men who lived lives before 1914 and beyond the theatre of war. I return to Paul Fussell’s quote (“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral”) and add that we must also see the soldiers who fought not as men, but as children. Again, the words of Edward Thomas serve to articulate this idea; the “summer past” including perhaps those lost years of childhood. Neil Hanson, writing in ‘The Unknown Soldier’ talks of how, on the eve of the Battle of the Somme, the smell in the air was that of an English summer – of fresh cut grass; the smell – one could say – of memories; of childhood.

Returning to Rilke’s Duino Elegies we find another dimension to these landscapes.

And gently she guides him through the vast

Keening landscape, shows him temple columns,

ruins of castles from which the Keening princes

Once wisely governed the land. She shows him

the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy

in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

These pastoral landscapes become therefore, not only the landscapes of childhood imaginings, of “personal memory and cultivated myth”, but the landscape of mourning. The words of Edward and Helen Thomas are especially poignant in this regard; Edward’s trees mourn for a long-lost past; Helen’s for an empty future.