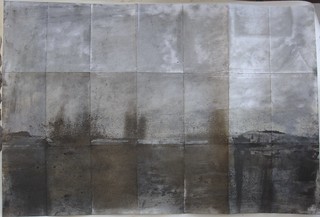

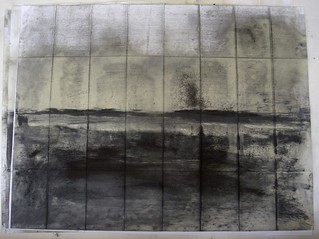

Extract from The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane.

“She [Helen Thomas] recalled afterwards that Gurney, on being shown the map, took it at once from her, and spread it out on his bed, in his hot little white-tiled room in the asylum, with the sunlight falling in patterns upon the floor. Then the two of them kneeled together by the bed and traced out, with their fingers, walks that they and Edward had taken in the past…

Helen returned to visit Gurney several times after this, and on each occasion she brought the map that had been made soft and creased by her husband’s hands, and she and Gurney knelt at the bed and together walked through their imagined country.”