The big coal ships have fascinated me ever since I first saw them when I arrived in Newcastle. Like the huge clouds above them, they seem on the face of it not to be moving, but rather – like a photograph – fixed in their shape. Only over a period of time, as one watches, do the ships reveal themselves as moving, changing their course, just as the seemingly immutable clouds change their shape.

The past too is like this. It appears to us fixed in its final shape by history, but when we observe at length we begin to see things differently – just as with the ships and the clouds, the past changes shape not unlike the way the present constantly changes its shape around us; because the past was once the present.

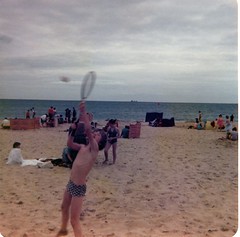

I have for a long while been interested in old photographs, in the distant parts of photographs where things are not the ‘subject’ of the picture. For example, the image below is a detail from a holiday snap taken some time in the early 1980s. I’ve no idea who the girl is and only noticed her when I enlarged the image.

Merleau-Ponty once wrote how distance was not a property of the horizon, and distance too – we might say – is not a property of those people occupying the background of these photographs. They are – or were – as much a part of the scene as those of us in the foreground – the subjects of the photograph. We are always as much a part of the distance and the foreground as everyone else; we are both these things at one and the same time. In terms of history, we in the present are like the subject of a photograph, and those in the past are like those in the distance. Everything is the same part of the present, just seen from different perspectives.

The past is as much about movement as is the present (just as the distance contains as much movement as the foreground) and to observe this movement in the past (or the distance) requires us to be patient – to watch and to listen.

It is interesting that watching and listening to the distance has become a theme during my residency here, and that the image above – a video still of the ships and the sky – was filmed from Shepherd’s Point, a place from which the Services would listen and watch for the enemy during World War 2.