Every Sunday, from when I was born to the age of 16, I went to church. It was in many respects – and still is, even though I no longer attend – the hub of family life, having played a central part in the life of my extended family from the moment my mum moved to Oxford with her family in 1952. I was christened there in 1971; my mum and dad were married there, as were my aunts and uncles and several cousins. Many members of my family met their partners in the Youth Club and of course we have said goodbye to family members; my Grandad in 1984, my Nan in 2010 and step-father in 2008.

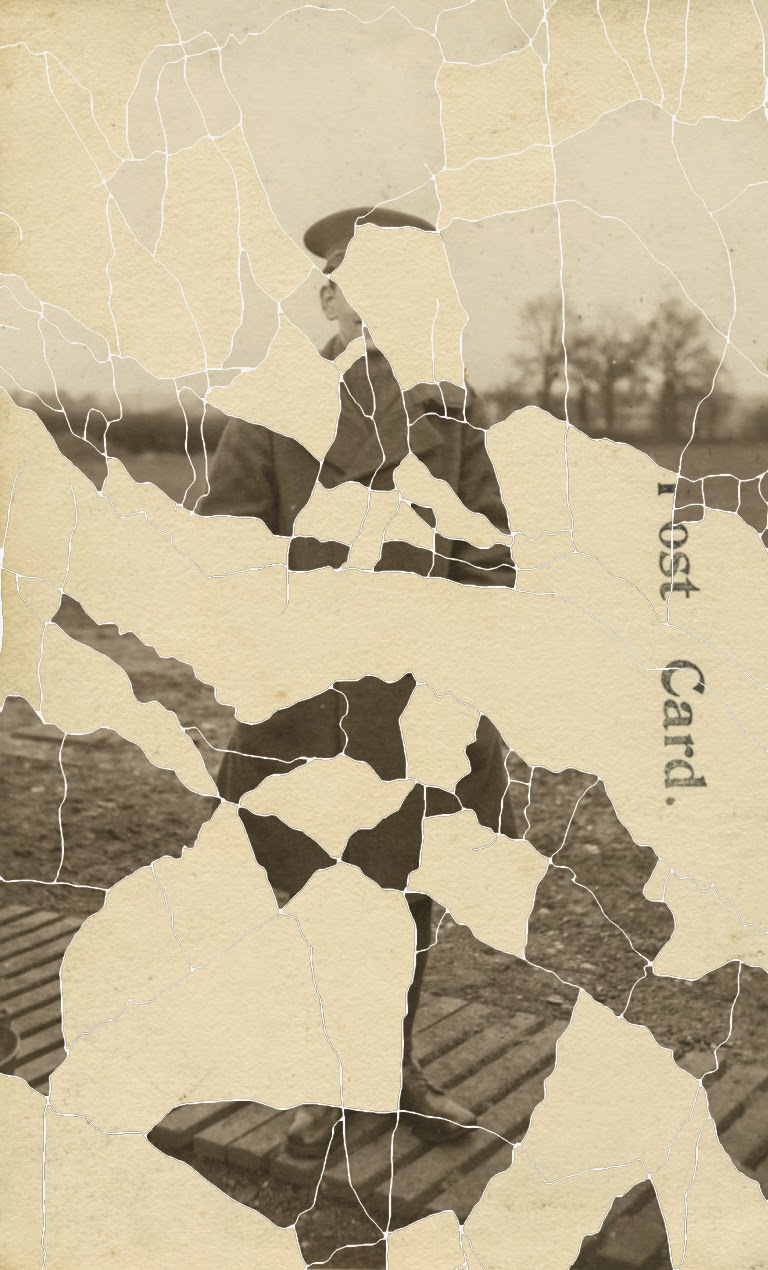

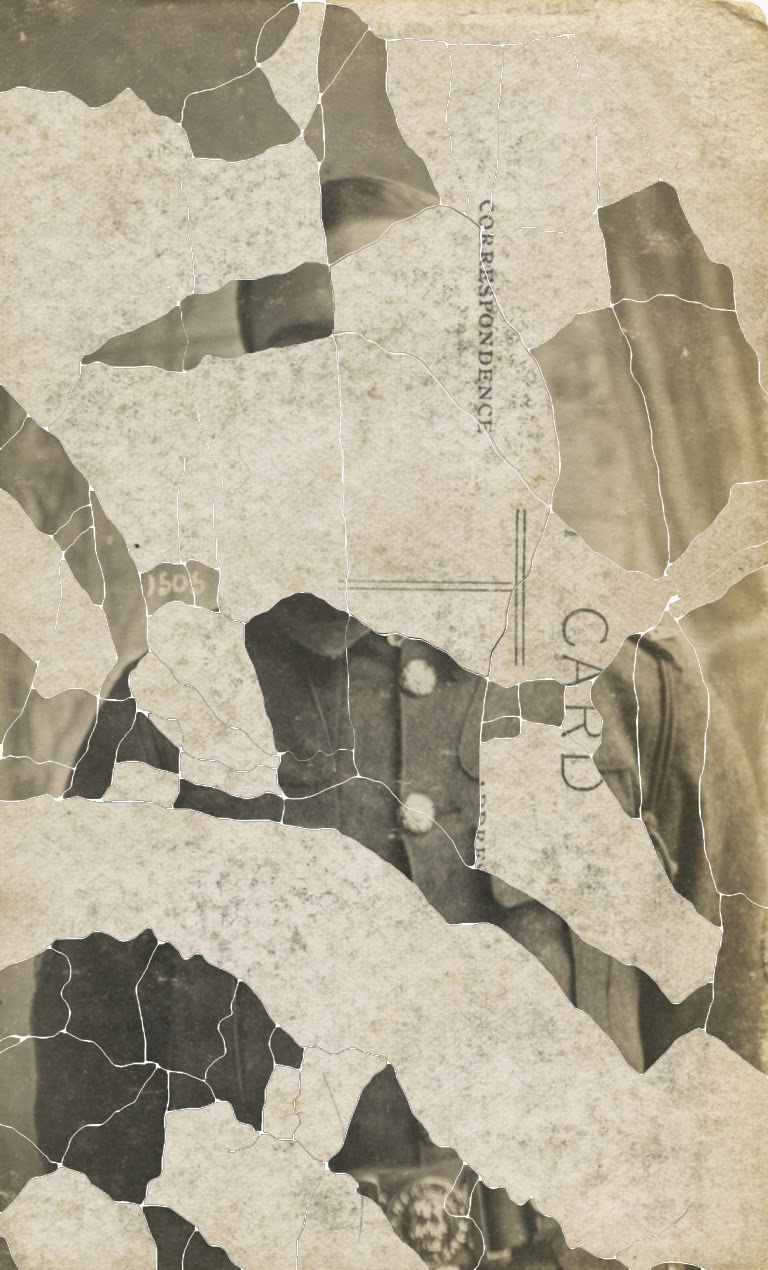

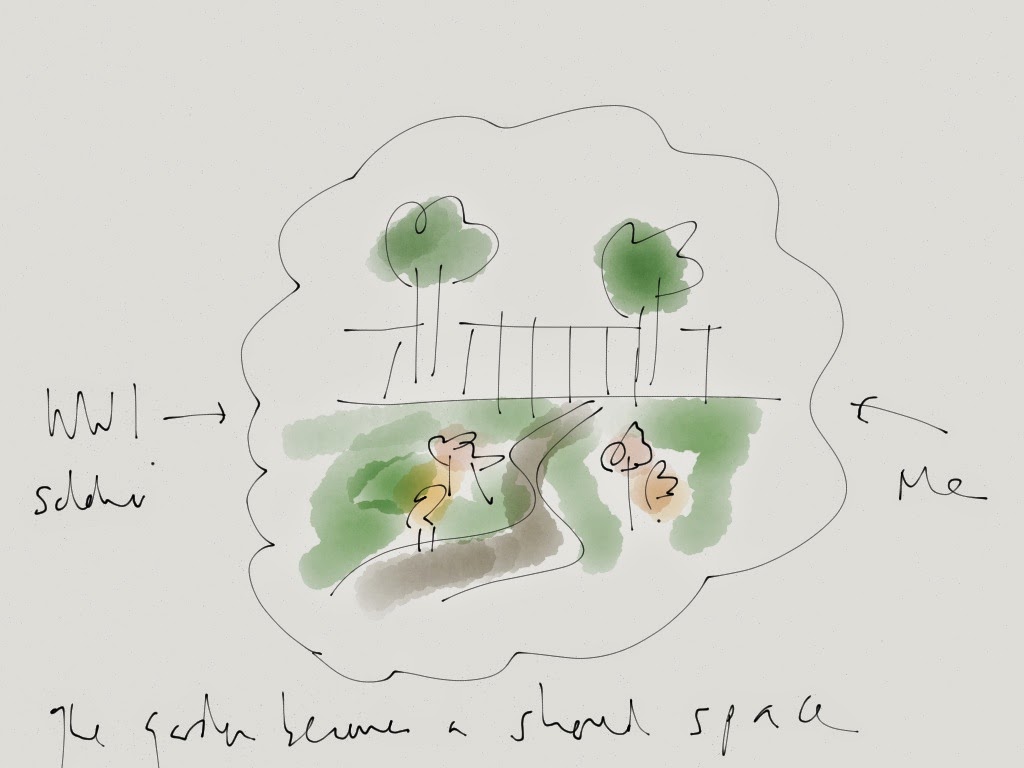

I doubt there is any place in the world that harbours so many memories for me, but the one I want to recall today isn’t a specific memory as such but rather a recollection. I recall how as a young boy, I used – when singing hymns – to look at the dates of birth and death of the authors, in particular John Wesley. It’s hard to say what I thought while looking at his dates (1703-1791); I can, as an adult, only interpret what that child was thinking. (Thinking about this now, it could be that it was Charles Wesley’s hymns we sang, in which case the dates would be (1707-1788). It could of course have been both). I remember too a plaque on the wall, dedicated to the memory of a man killed in the Second World War. Again there was something about the dates that captivated me – a date from a time – and a place – before I was born.

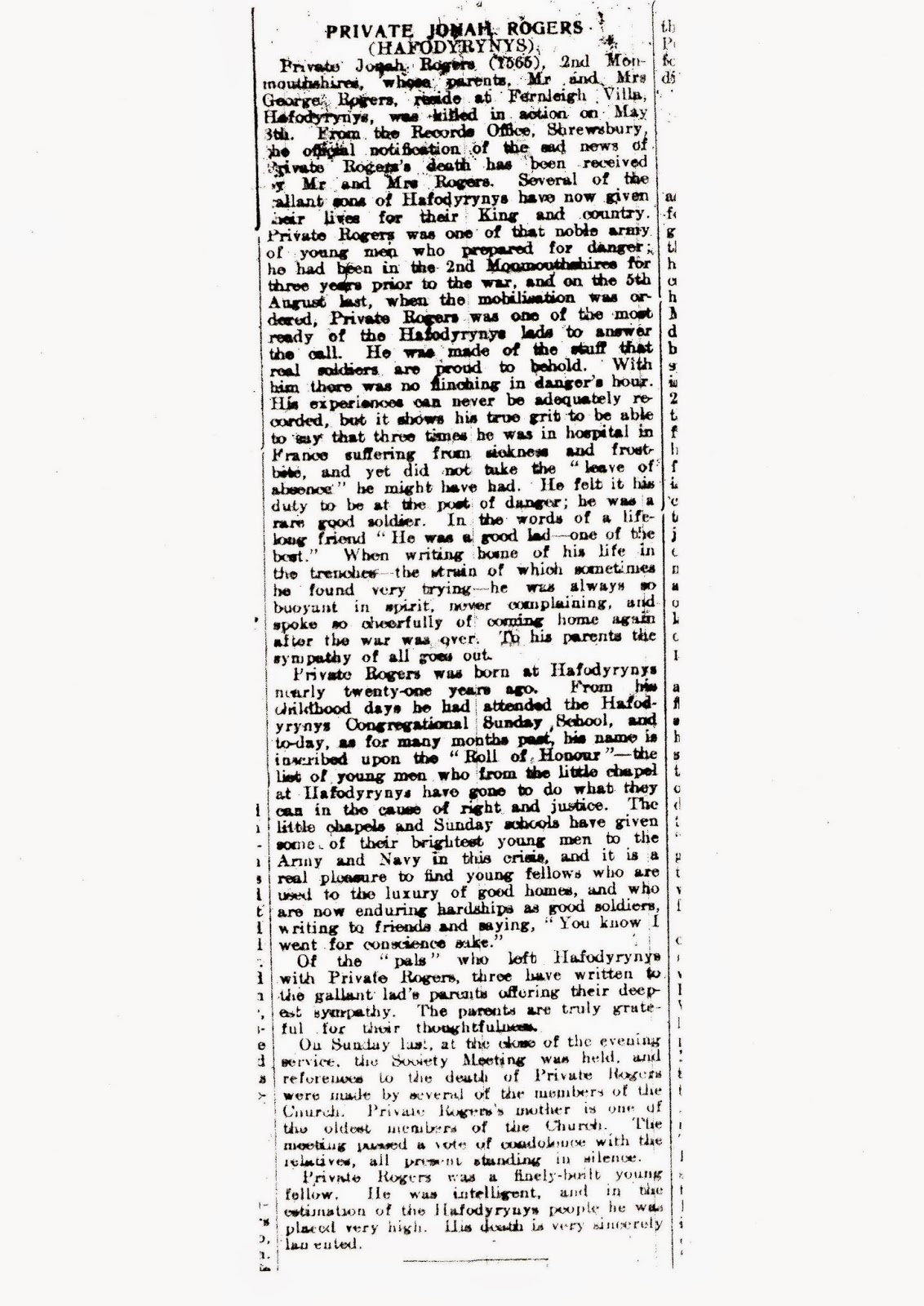

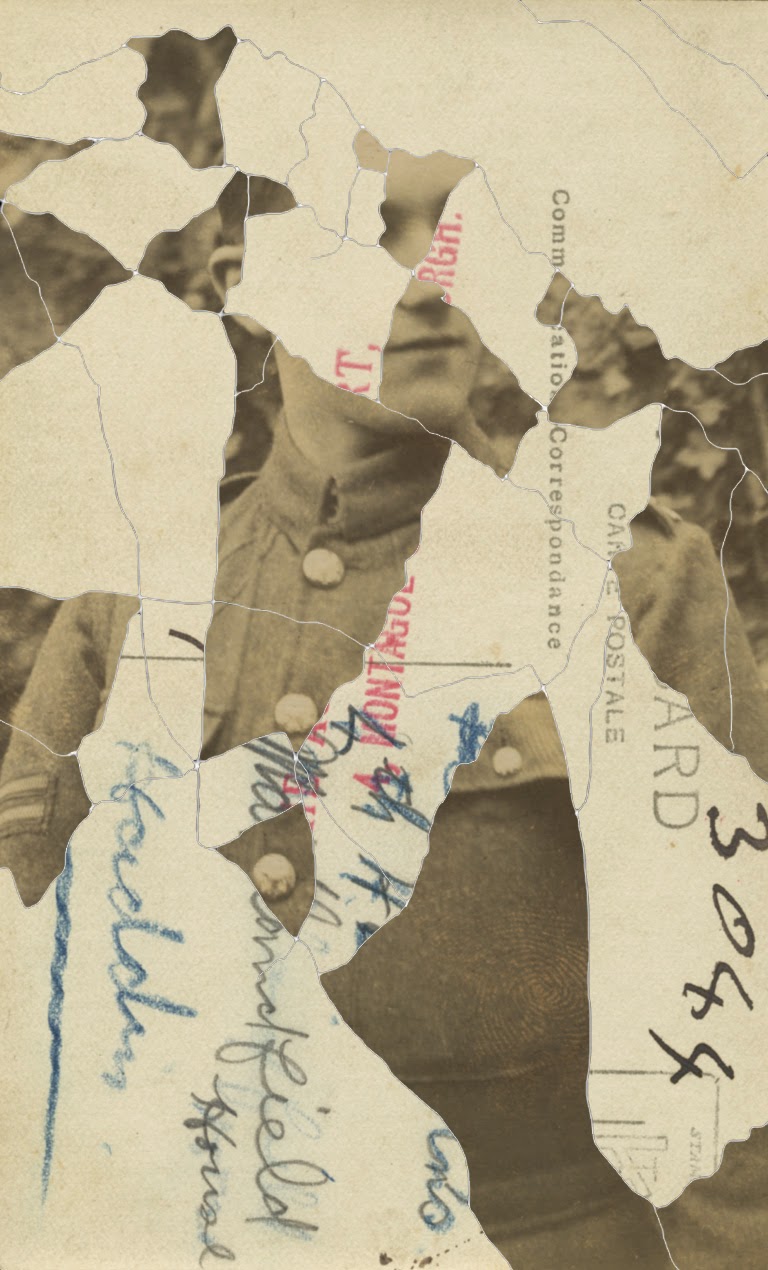

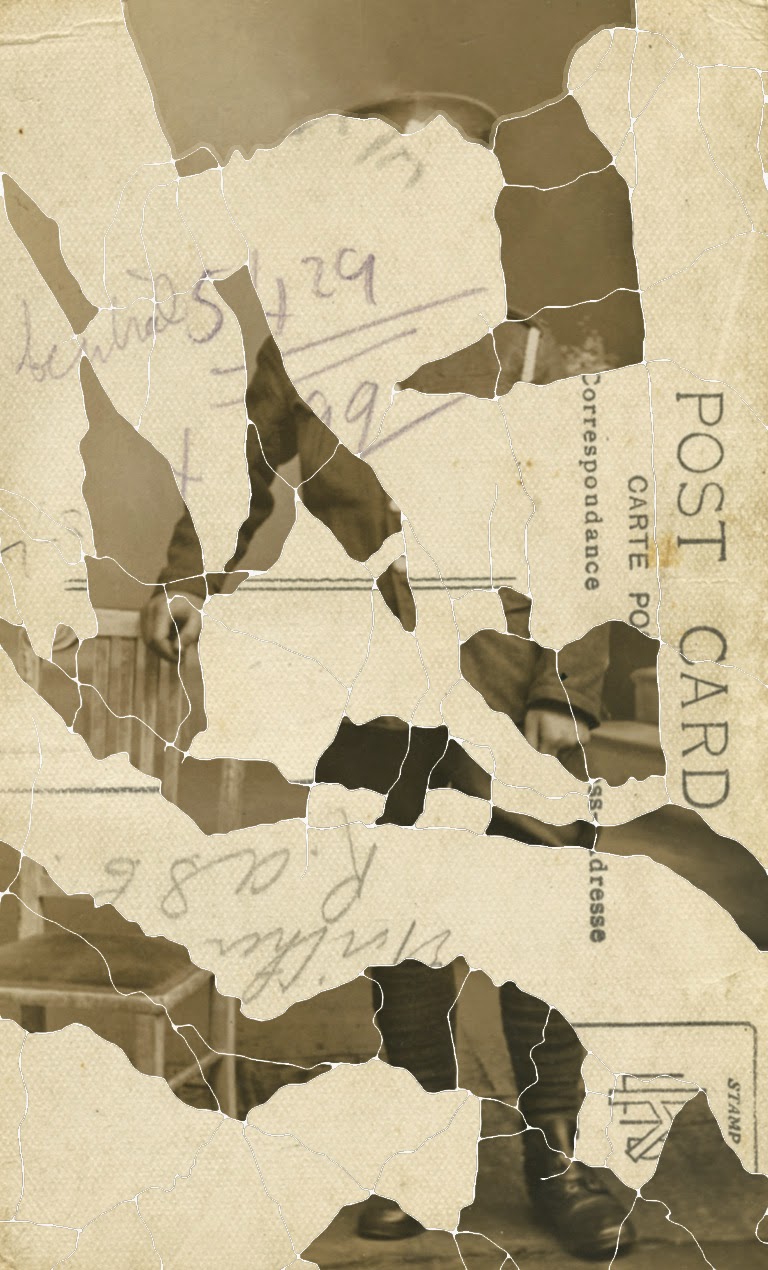

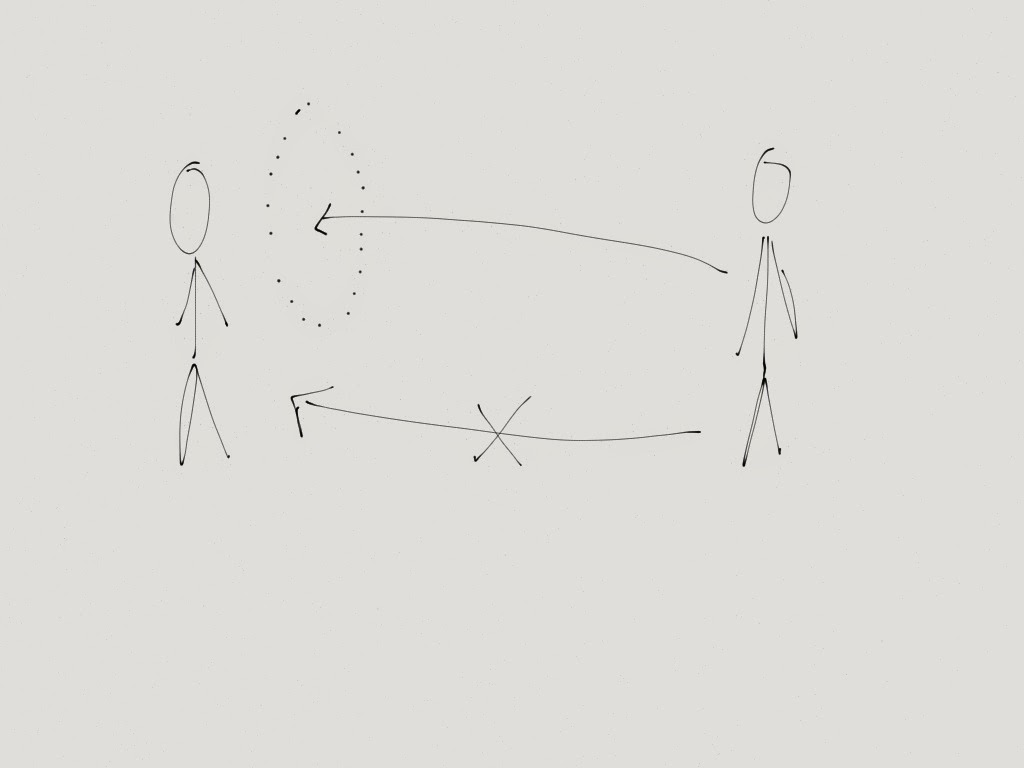

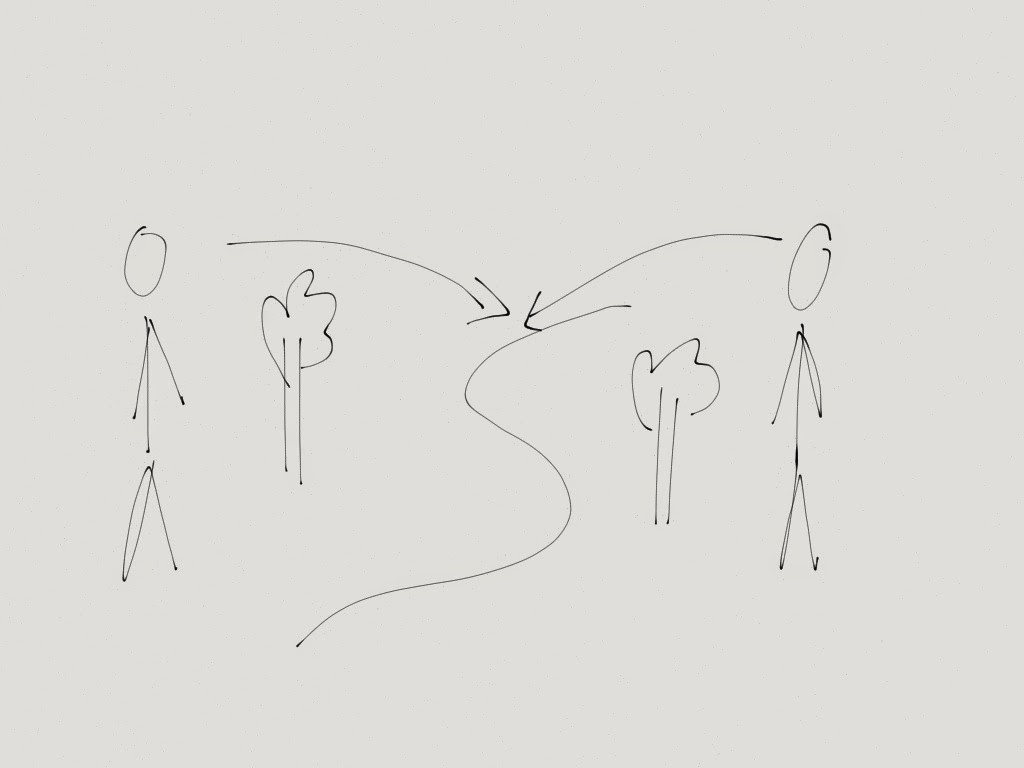

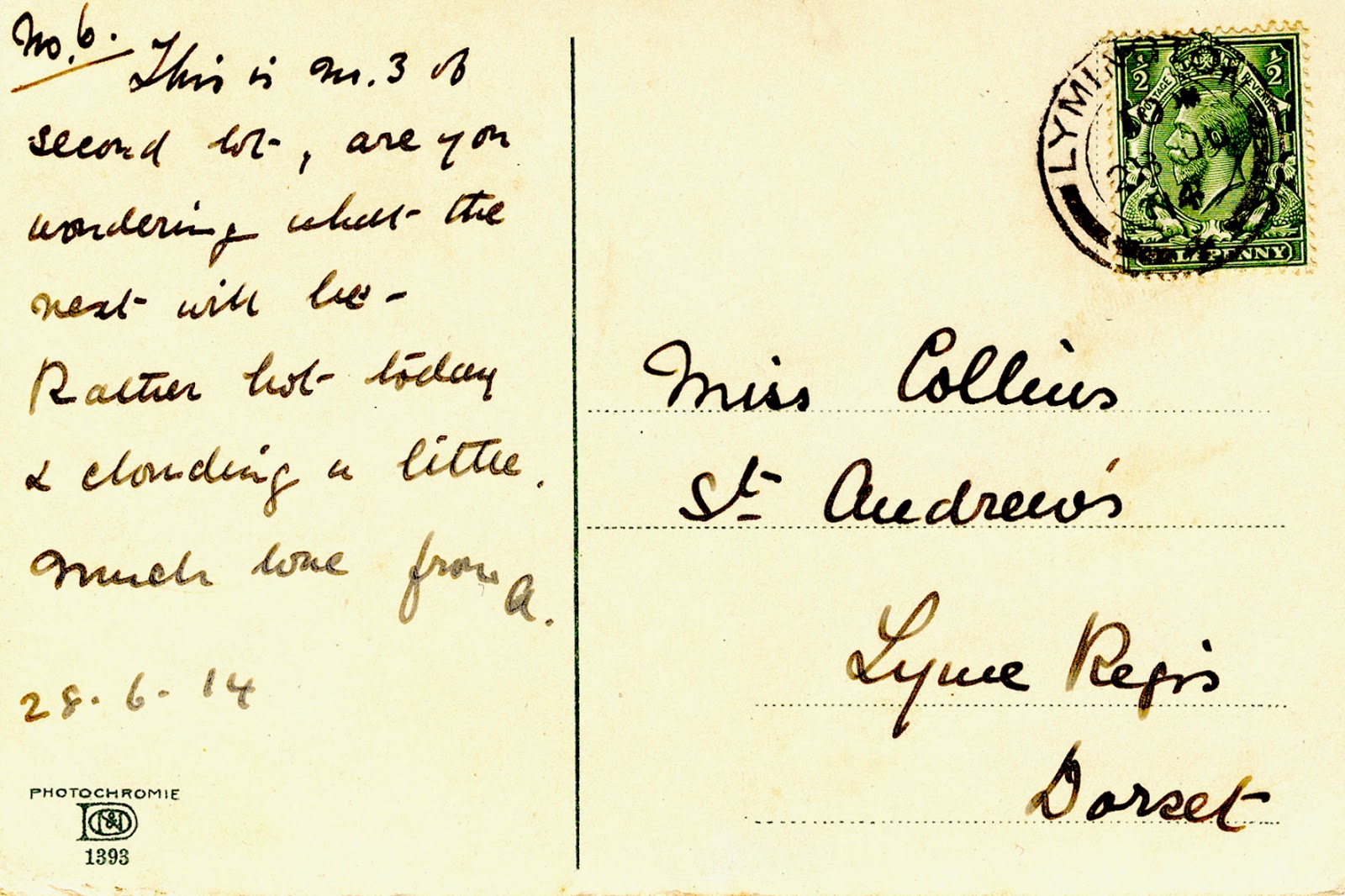

The dates of someone’s birth and death delineate a space, much as a boundary on a map, a place that existed but doesn’t anymore. They are coordinates for the beginning and end of a journey.