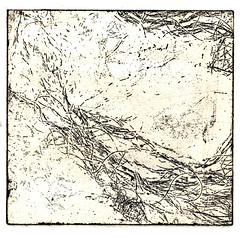

The following drawing is part of a series I’ve been working on regarding Auschwitz-Birkenau and the theme of pathways.

Looking at the picture, I was reminded of something which for a while escaped me. There was something about the tower in particular which I was sure bore a striking resemblance with another, famous painting.

The following is a detail from the drawing.

Looking at it closely, at the apparent anguish and suffering in the ‘face’ of the tower (the tower as suffering goes against all I have written about it so far: “…the gate house is different, it knows its time has passed but doesn’t seem ashamed in anyway. Its almost as if it relives every moment in its glass eyes, glass eyes which are far from being blind. They don’t reflect what they see around them now but rather what has been, what the tower wants to remember…”) made me think at once of the painting I’d been thinking of, an image painted in 1937 and again, one of the utmost despair: Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’.