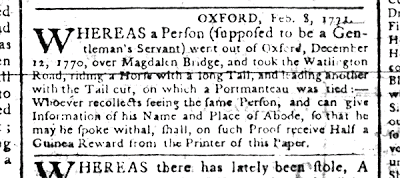

The bridge over which our Gentleman’s Servant rode in December 1770 is not the same bridge which crosses the River Cherwell today. Being as it is an important part of the story, I’ve copied an entry on the bridge from The Encyclopaedia of Oxford1 which I’ve reproduced below.

A bridge, formerly known as Pettypont and East Bridge, has stood here since at least 1004. In the Middle Ages the cost of its upkeep was shared between the county and the town, the town meeting its three-quarters share largely by alms and charitable bequests, the maintenance of bridges being then considered a pious duty. Bridge-hermits were also appointed to help travellers with any difficulties they might experience in crossing. The original bridge was of wood, but by the 16th century a stone bridge, some 500 feet long, with about twenty pointed and rounded arches, had been constructed.

At this time the city was still paying for repairs, both by taxation and by the allocation of alms; but William of Waynflete, the founder of Magdalen College, may have paid for restoration of the bridge in the 15th century, and the University certainly did so in 1723. Although a major restoration was then undertaken, less than fifty years later some of the piers had been swept away by floods and the western end had collapsed completely. Condemned as dangerous, it was rebuilt between 1772 and 1778 under the provisions of the Oxford Improvement Act of 1771, to the design of John Gwynn. At the same time a toll-house was built at The Plain, with gates across the roads from Headington to Cowley to collect dues for the maintenance of the bridge. Twenty-seven feet wide, with recesses in the middle, the bridge’s large semi-circular arches were supplemented by smaller ones over the towpaths. The plain balustrade was designed by John Townesend after plans for a more elaborate one had been dropped. The bridge was widened in 1835 and again in 1882. Notabilities have frequently been welcomed or taken their official departure at the bridge, as Queen Elizabeth I did on leaving Oxford in 1566.

1 The Encyclpaedia of Oxford, 1988, Ed. Christopher Hibbert, Assoc. Ed. Edward Hibbert; London, Macmillan London Limited