Buried in St. Sepulchre’s, Jericho.

Silence as Other

The past is silent. To know the past, one must know silence.

The theme of silence has come up a lot in my work, something I’ve written about before (see Augmenting Silence), and it was whilst re-reading a blog on Chinese painting that I began to consider – within the context of what I’d written – silence as other.

In that blog I wrote:

There’s a quote I’ve often used from Christopher Tilley. In his book, The Materiality of Stone – Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, he writes:

The painter sees the trees and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would be impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects… The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to how a mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders for him something that would otherwise remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… the trees and mirror function as other.

Like the trees, the mountains share that agency; they too ‘see’ the painter’ and it’s almost as if the painting becomes a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It’s not the mountain that is made visible on the paper, but the artist’s outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence.

I would add now, that, like the trees and the mountain described, silence works in the same way. To empathise with the past, as I’ve written many times before, we must understand what it means to be present, and silent meditation is a great way to do that. Sitting in the garden and listening in silence, one realises how silence comprises many ‘layers’ of sound (and other sensations); how the nowness of now comprises many ‘parts’.

The past too comprises many layers or parts, most of which have been stripped away by the very fact of their pastness. Now the past is silent, but by understanding that silence, we can find a way back.

Another blog entry (An Archaeology of the Moment) backs this up. In it I wrote how in his book Figuring it Out’ Professor Colin Renfrew writes:

The past reality too was made up of a complex of experiences and feelings, and it also was experienced by human beings similar in some ways to ourselves.

The way we experience the present then, tells us a great deal about how people experienced the past when it too was the present.

In a blog about a distant ancestor Thomas Noon (The Gesture of Mourning), I wrote about standing at the grave of him and his children who pre-deceased him; how he would have stood there:

“I can imagine him there, listening as I can to the wind in the trees. He sees the same late-winter sun and feels its warmth on his face. I can, as I have done, read about his children and their untimely deaths. I can read about him. But standing at their grave, my imagined versions of them are augmented by the gesture of my body.”

Back to the blog entry Augmenting Silence. In it I gave three extracts from old newspapers:

“On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.” (1915)

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.” (1842)

“Her mother got up and tried the door but it was locked by [the] witness when her father and mother came in. Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.” (1852)

What interested me about these quotes were the silences. When I became aware of them, I realised I was empathising with the story much more readily. I could almost sense myself in the amongst words and the scenes they described. To repeat what I wrote earlier:

“Like the trees, the mountains share that agency; they too ‘see’ the painter’ and it’s almost as if the painting becomes a painting, not of Yu Jian looking at the mountains, but of the mountain ‘seeing’ Yu Jian. It’s not the mountain that is made visible on the paper, but the artist’s outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence.”

If silence is ‘other’, how can it be shown in a work? The answer is revealed in the following from Augmenting Silence. As I wrote:

In all three quotes, the ‘revelation of silence’ comes after the ‘facts’:

“The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.”

“Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.”

“…the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon… but unaccompanied by thunder.” Silence is not the subject of the texts, but a part which serves to illuminate the whole (which in the second extract is especially pertinent).

It’s like the opening of a camera’s shutter; everything that came before it is condensed into a moment.

Also, as I looked into my work, I realised that ‘silence’ appeared in ‘Heavy Water Sleep‘:

Outside a window stands silent, the surrounding

covered with heavy water sleep.

There is no sound and no movement

dropping through the

closed rude

earth.

a man advancing with resolute step

But for the heavy steps,

there is silence.

time Meanwhile

emerges

from a hole in the day before

and

pulls impatiently

at the window stops Outside

the so-lately deserted

Silence

the Extraordinary story

that lies behind this scene

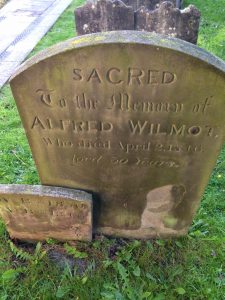

Alfred Wilmot

Having photographed the grave of Henry Sides, I took one of another grave which had caught my eye whilst walking the same path. This belonged to an Alfred Wilmot:

Harriet Sides

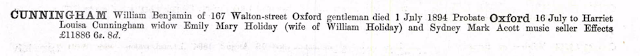

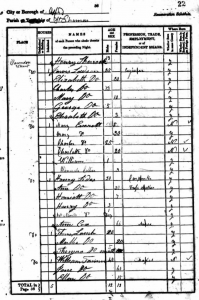

Harriet Sides was the eldest daughter of Henry Sides. Born in 1834 she was married to William Cunningham in 1871 age 37. William Cunningham was born in 1826 in London to a William and Mary Cunningham and in 1861 is shown to be living at 20 Broad Street, Oxford.

In 1881, Harriet and William were living in Kidlington, Oxford with their two children, Clifford (6) and Walter (4). In 1891 they were living at 167 Walton Street, Oxford along with their two children and a servant, Clara Seppury.

William died on 1 July 1894 leaving £11,886 6s 8d in his will – almost £1.4 million in today’s money.

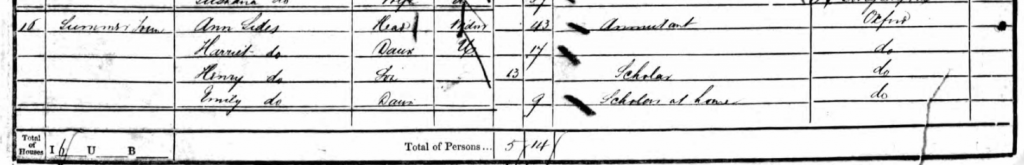

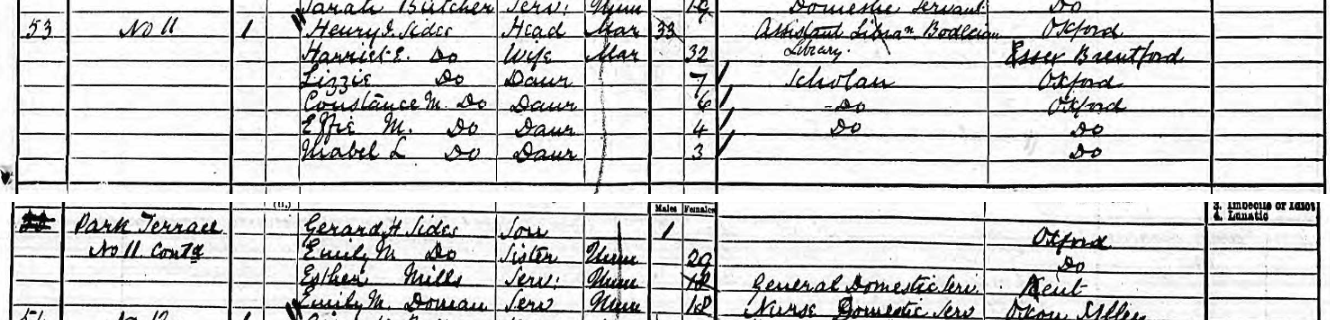

Henry Sides and family

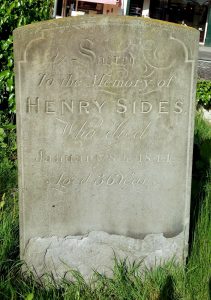

Everyday, on my way to catch the bus after work, I pass by this grave at the edge of the path which cuts through St Giles churchyard.

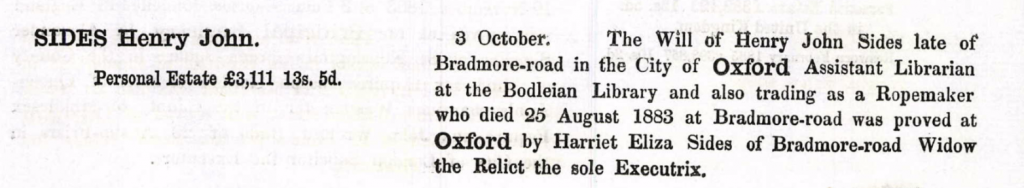

Ten years on, in 1881, Henry and Harriet have extended their family still further, with the arrivals of Arthur, Herbert, Gertrude and Archibald. They had moved too, living now in Bradmore Road with a Cook and a Nursemaid. At 42, Henry is still an assistant librarian and partner in a firm of rope makers.

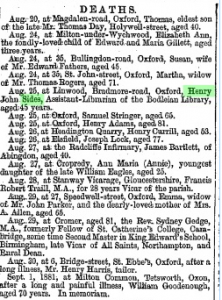

Henry John Sides died on 25th August 1883, aged just 45…

Centenary

100 years ago, on 8th May 1915, my great-great-uncle was killed in the Second Battle of Ypres.

I’ve written before about this photograph and in particular its location; the idea of the garden as a shared space of memory and experience. Recently, in our own garden we had to have an apple tree taken down due to the fact it had been hollowed out by heart-rot and was in danger of toppling over. I asked for the trunk of the tree to be save in one piece, and when I saw it on the ground, I was reminded again of the idea of gardens as described above.

The trunk of the tree resembled a torso missing its head and limbs.

There was something interesting in the way the bark had grown over a length of wire which had been wrapped around the trunk years ago. It called to mind the cascading lengths of barbed wire rolled out in front of the trenches. It also seemed to turn the trunk into a corpse.

At the same time the tree Is symbolic of a lost idyll; that of the garden of childhood memories.

An Odyssey in Time

A couple of days ago, I read the following passage in ‘The Odyssey’ in which Homer describes how Odysseus and his men escaped from the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus.

As for myself,

I chose the finest ram in the flock, and I grabbed it

and swung myself under its shaggy belly and clung there

face upwards, my fingers tightly gripping its wool

and as patient as I could be. In this way, with moans

and tears, we hung from the rams and waited for morning.

As soon as the flush of dawn appeared in the heavens,

the males of the flock began to go out to pasture,

while the females, unmilked, their udders now full to bursting,

bleated beside the pens. Their master, still racked

with hideous pain, felt all along the rams’ backs

as they stopped in front of him on their way out, but the fool

never realized that 1 had tied my companions under their bellies.

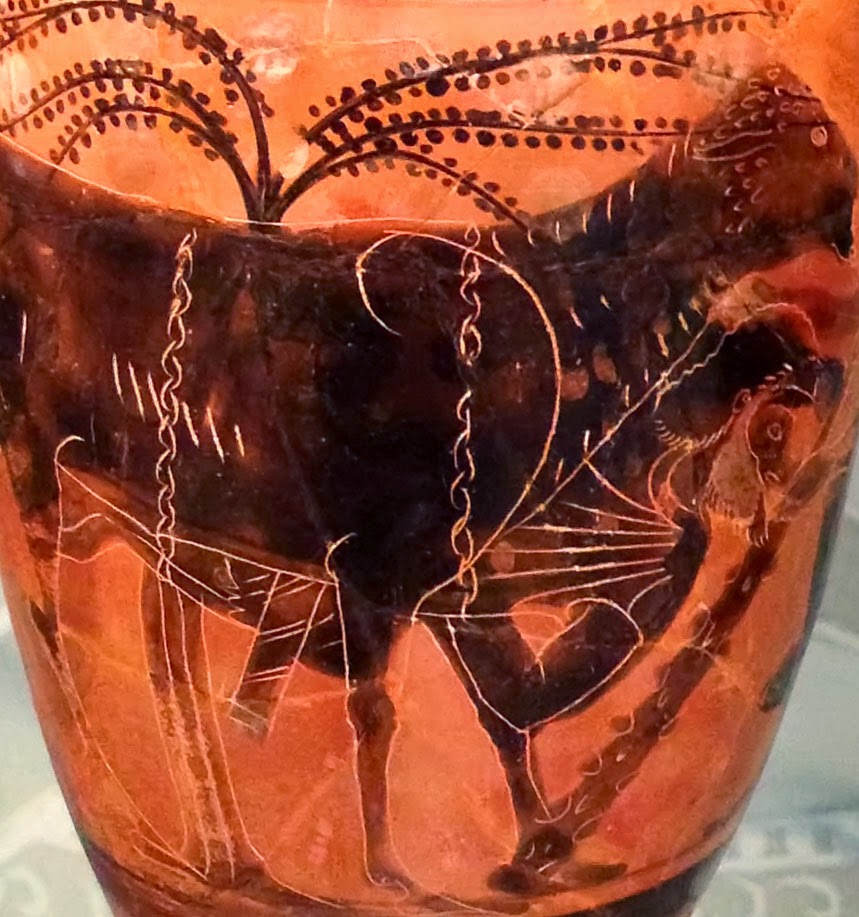

Yesterday, I had a wander in the Ashmolean Museum and discovered this:

It’s a jug dating from 550-501 BC which shows in its decoration, the moment Odysseus steals himself out of Polyphemus’ cave under the ram.

It was a particularly strange sensation, to have in my memory, a piece of text I’d so recently read and to then find it illustrated on an object which was 2,500 years old.

P is for Pastoral

In her book H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald writes [my paragraphing]:

“Long walks in the English countryside, often at night, were astonishingly popular in the 1930s. Rambling clubs published calendars of full moons, train companies laid on mystery trains to rural destinations, and when in 1932 the Southern Railway offered an excursion to a moonlit walk along the South Downs, expecting to sell forty or so tickets, one and a half thousand people turned up.

The people setting out on these walks weren’t seeking to conquer peaks or test themselves against maps and miles. They were looking for a mystical communion with the land; they walked backwards in time to an imagined past suffused with magical, native glamour: to Merrie England, or to prehistoric England, pre-industrial visions that offered solace and safety to sorely troubled minds. For though railways and roads and a burgeoning market in countryside books had contributed to this movement, at heart it had grown out of the trauma of the Great War, and was flourishing in fear of the next.

The critic Jed Esty has described this pastoral craze as one element in a wider movement of national cultural salvage in these years…”

This quote interested me in that it tied in with another by Paul Fussell who wrote:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

Putting these together, I’m reminded as I’ve often written about before of my childhood, when I would create maps of imagined countries (which were in effect imagined pasts) in which I would mentally walk whilst out walking.

One day in 1845

The fact that we exist, as the individuals we are, is mind-boggling. Go back 8 generations and you’ll discover that you have 256 great-great-great-great-great-great-grandparents. Go back to the start of the 1600s and you’ll discover that you owe your existence to 1,024 people who were alive at the time; 2,046 including those who came after.

No-one of course lives their lives in isolation. We spend every day interacting with friends, family or strangers, and as such, all those people too have influenced our coming-into-being.

My 9th great-grandfather, Gabriel Baines (born in 1610) was one of 1,024 people alive around the time on whom my existence has depended. Factor into that equation, that everything (and I mean everything) those 1,024 people did in the early 1600s had to be done exactly as it was, then you begin to appreciate how extremely unlikely you are. (Extrapolate this out and one could say that everything that everyone did had to be done as it was for any of us to be born who were are.)

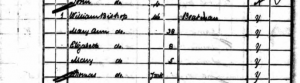

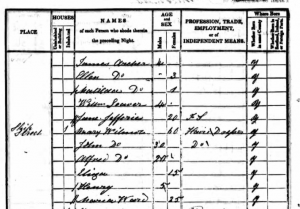

Leaping ahead from the early seventeenth century to the mid 19th century I find my great-great-great-grandparents. Since beginning my research in 2007 I have discovered all 32 of them. Imagine then a day in 1845. All 32 of these individuals were living in England and Wales (their ages and place of residence at the time shown in brackets).

Richard Hedges (37 – Dorchester, Oxfordshire)

Ann Hedges née Jordan (38 – Dorchester, Oxfordshire)

Elijah Noon (27 – Oxford, Oxfordshire)

Charlotte Noon née White (26 – Oxford, Oxfordshire)

William Lafford (21 – Ampney St Peter, Gloucestershire)

Elizabeth Timbrill (18 – Minety, Gloucestershire)

Abel Wilson (27 – Ampney Crucis, Gloucestershire)

Hester Wilson née Pillinger (22- Ampney Crucis, Gloucestershire)

Alexander Jones (44 – Mynyddyslwyn, Monmouthshire)

Martha Jones née Harries (27 – Mynyddyslwyn, Monmouthshire)

Edmund Jones (28 – Trevethin, Monmouthshire)

Sarah Jones née Jones (27 – Trevethin, Monmouthshire)

Enos Rogers (4 – Clutton, Somerset)

Jane Tovey (4 – Llanfoist, Monmouthshire)

Alfred Brooks (7 – Bettws, Monmouthshire)

Ruth Waters (5 – Machen, Monmouthshire)

John Stevens (33 – Reading, Berkshire)

Elizabeth Stevens (28 – Reading, Berkshire)

Charles Shackleford (28 – Reading, Berkshire)

Mary Ann Jones (20 – Reading, Berkshire)

John Thompson (31 – West Walton, Norfolk)

Maria Thompson née Hubbard (33 – West Walton, Norfolk)

William Baines (20 – Gainsborough, Lincolnshire,)

Martha Baines née Moore (20 – Gainsborough, Lincolnshire,)

George Sarjeant (31 – Lewes, Sussex)

Sarah Sarjeant (39 – Lewes, Sussex)

James Barnes (23 – Arlington, Sussex)

Eliza Barnes née Deadman (21 – Arlington, Sussex)

Henry White (46 – Brighton, Sussex)

Mary Ann White née Ellis (29 – Brighton, Sussex)

John Vigar (36 – Worth, Sussex)

Elizabeth Vigar née Simmons (33- Worth, Sussex)

For a bit of background: in 1845 the Prime Minister was Robert Peel. On 15th March the first University Boat Race took place and on 1st May the first cricket match as the Oval was played. The rubber band was patented and the last fatal duel between two Englishmen was fought on English soil. Potato blight in Ireland saw the start of the Great Famine.

The Gesture of Mourning

Graveyards and cemeteries have always fascinated me. The feeling I have when entering them, is much the same as when I enter a museum, a sense of calm mixed with expectation as I wonder whose story or stories I’ll encounter.

Graveyards are archives; the headstones, documents on which we find the names and dates of those who’ve gone before us. But they are much more than that.

My family tree is an archive, one currently comprising almost 1,000 individuals. Poring through documents (albeit ones which are digitised), I discover names, locations and dates, much as you do when walking through a graveyard.

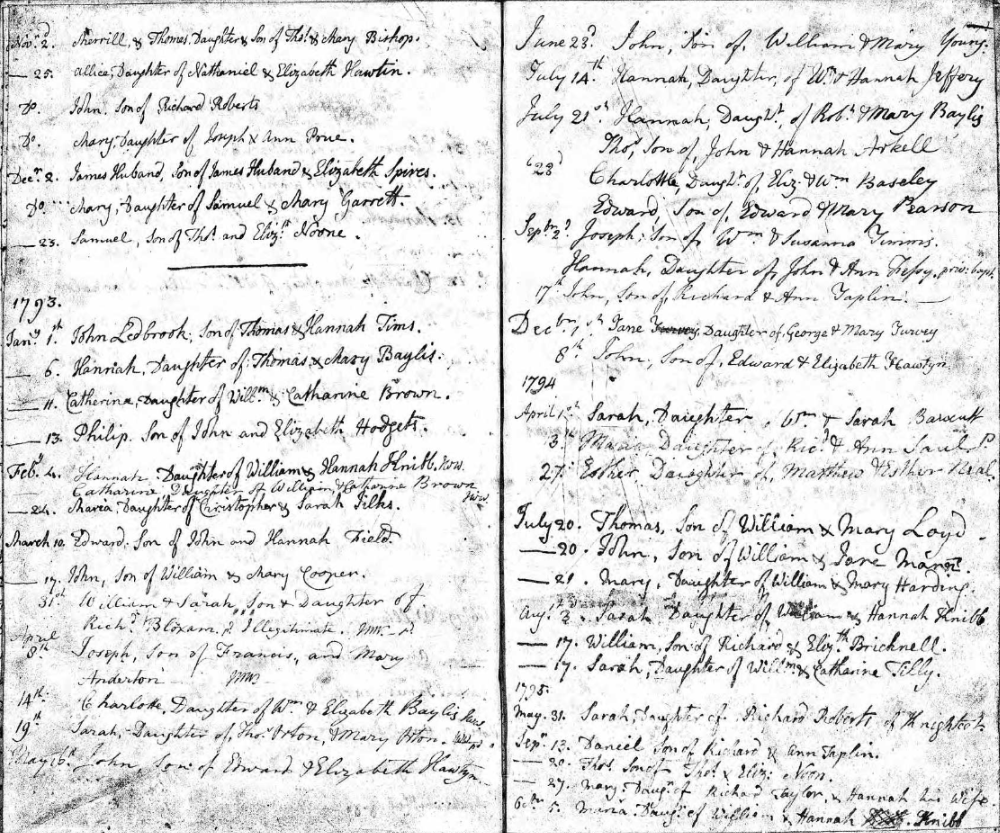

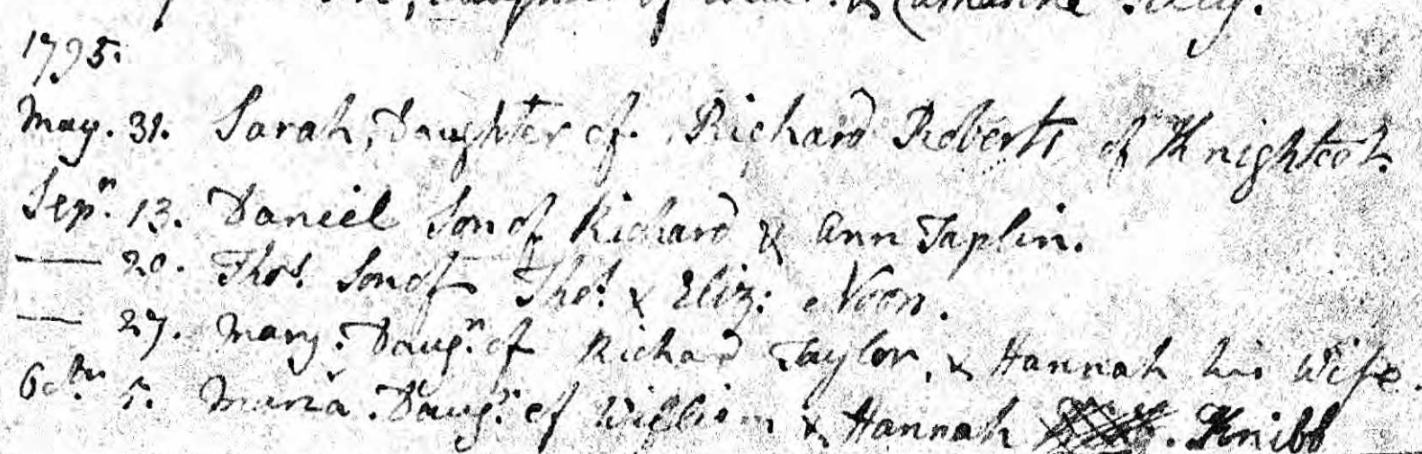

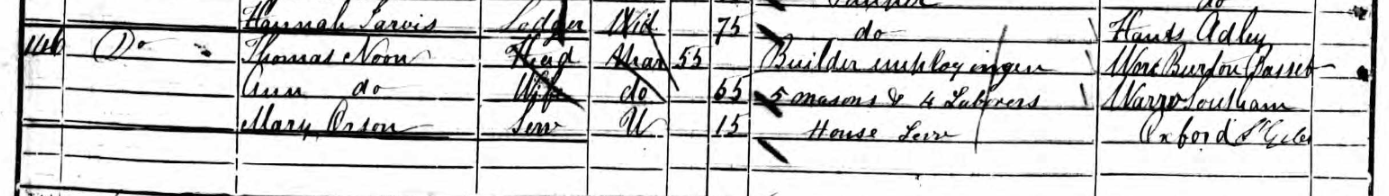

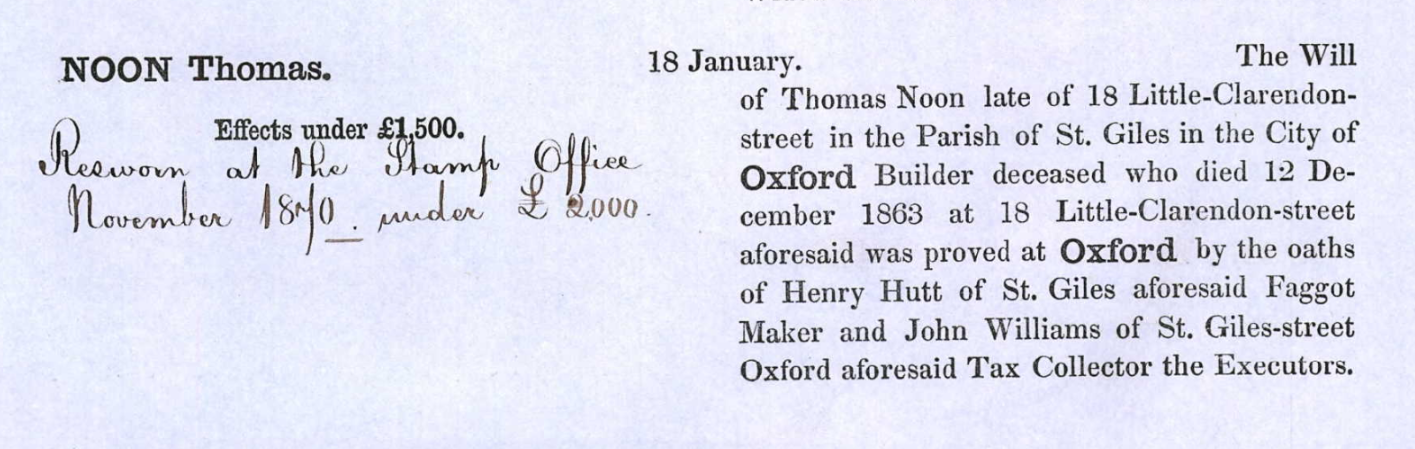

Thomas Noon was my great-great-great-great-uncle. He was born in Burton Dassett, Warwickshire in 1795. He was baptised there on 20th September.

At some point between 1824 (the birth of his daughter Betsy) and 1830 (the birth of his son Thomas) he moved with his family to Oxford.

In 1841 Thomas spent census night away from Oxford, but we find him in 1851, along with his second wife Ann.

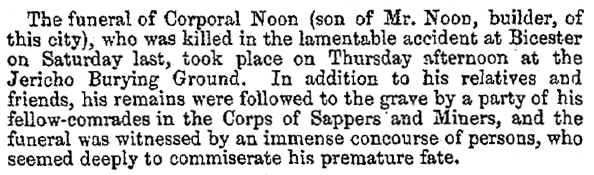

By this time Thomas had already buried his first wife Mary (1832 or 1840) and their three daughters – Emilia (1837), Eliza (1846) and Betsy (1850). In September of this census year, Thomas would also bury his son, killed in a train crash at Bicester. In 1852, tragedy would strike again when his brother Elijah killed his own wife with a sword at their house in Jericho.

Thomas died in 1863 at his home in Little Clarendon Street.

Through archive sources we can piece together his life, in censuses, baptism records, probate records and newspapers.

As we consider his terrible losses, we can sympathise with him but standing at his grave, the one he shares with his son Thomas and his daughter Betsy, that sympathy turns to empathy.

Like the name Thomas Noon, found in the documents described above, we find the name on his gravestone (below), weathered and worn to almost nothing (NB the name Thomas Noon and Betsy have been enhanced).

I can trace his name with my finger, and as I stand there, looking down at the grave, everything changes. I might be thinking, but my body is mourning.

First Betsy and then Thomas Jr were buried in that very grave over a decade before their father. How many times in those intervening years did Thomas stand where I was standing, looking down at that same patch of ground, thinking of his children? It’s as if, standing there over 150 years later, with the bearing of a mourner, I not only find Thomas within my imagination; I find myself within him too.

I can imagine him there, listening as I can to the wind in the trees. He sees the same late-winter sun and feels its warmth on his face. I can, as I have done, read about his children and their untimely deaths. I can read about him. But standing at their grave, my imagined versions of them are augmented by the gesture of my body.

They move in that space where the boundary between imagination and memory is blurred.

Thomas Noon’s Grave

I’ve just been to visit the grave of my great-great-great-great-uncle, Thomas Noon (1795-1863) in St. Sepulchre’s cemetery, Jericho.

Buried with him are his children, Betsy Markham née Noon (1824-1850) and Thomas Noon (1830-1851) who was killed in a train crash at Bicester.

Not far from the cemetery is Freud cafe, once St Paul’s church and the place where Eliza Noon married William Cartwright (1842) and Betsy Noon married Thomas Markham (1844).

Thomas Noon (1795-1863)

Having scanned the pages of Jackson’s Oxford Journal for more information on my great-great-great-great-uncle Thomas Noon, I decided to Google his name whereupon I came across the St Sepulchre’s website which contains a great deal of information on him and his family (St. Sepulchre’s being the cemetery in which they are buried).

I knew a little about Thomas (see The Victorians) such as the fact his son – also Thomas – was killed in a train accident in Bicester in 1851, but I didn’t realise just how much his family suffered in the few years before and after.

Thomas was married to Mary Flecknoe in Daventry on 14 August 1820. Their children included:

Eliza Noon (born 1821)

Betsey Noon (born 1824)

Thomas Noon (born 1830)

Emilia Noon (born 1832)

Mary Noon died before 1841 and there are, according to the St. Sepulchre’s website entry two possible burials:

Mary Noon who died at the age of 36 in 1832 (buried in St Thomas’s churchyard on 29 November), and Mary Ann Noon, stated to be of Jericho, who died at the age of 39 in 1840 (buried at St Peter-in-the-East churchyard on 3 May).

My hunch would be that our Mary Noon is the first of these. I can’t quite see why she would be buried in St. Peter-in-the-East, even though it states that that particular Mary was of Jericho. Given the date of 1832 – the year Emilia was born – it could be she died in childbirth. It would appear that Emilia herself died in 1837.

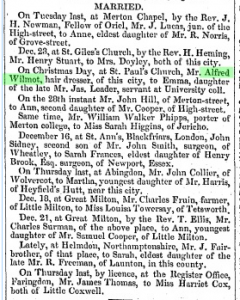

Two of Thomas’ daughters were married in the early 1840s at St. Paul’s church, which is now Freud’s cafe.

On 13 January 1842 at St Paul’s Church, Eliza Noon married William Cartwright, a coal dealer. They had both been living in part of the same house in Clarendon Street, and Eliza was described as being the the daughter of Thomas Noon, publican.

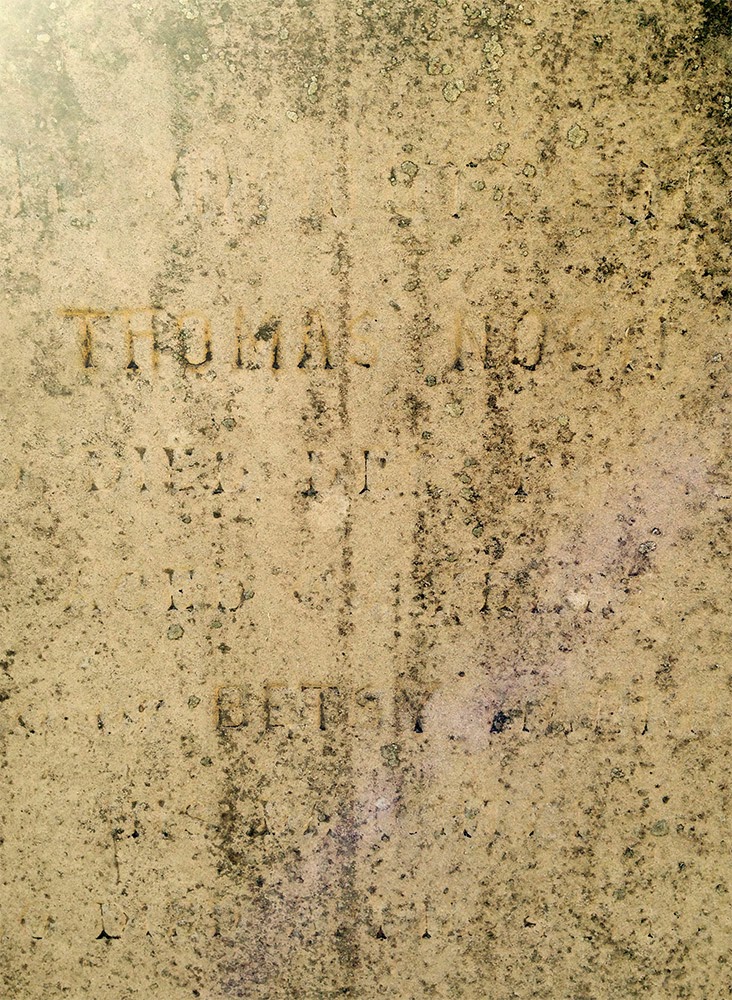

On 15 August 1844 at St Paul’s Church, Betsey Noon married Thomas Markham, a tailor, born in Oxford in c.1820. Both were described as being of Clarendon Street, and their marriage was announced in Jackson’s Oxford Journal.

Then came several tragic years for Thomas Noon.

Eliza disappears after the 1841 census, and may be the Elizabeth Cartwright who died in the Jericho district at the age of 24. She was buried in St Giles’s churchyard on 25 January 1846.

Betsey died 4 years later, at the age of 26 and was buried in St. Sepulchre’s.

A year later, Thomas (Jr) was killed in a train crash at Bicester. He was buried with his sister, his funeral described in Jackson’s Oxford Journal.

The following year, 1852, his brother, Elijah, killed his wife in Jericho. Thomas died in 1863 and was buried in the same grave as his son Thomas and his daughter Betsey.

Augmenting Silence

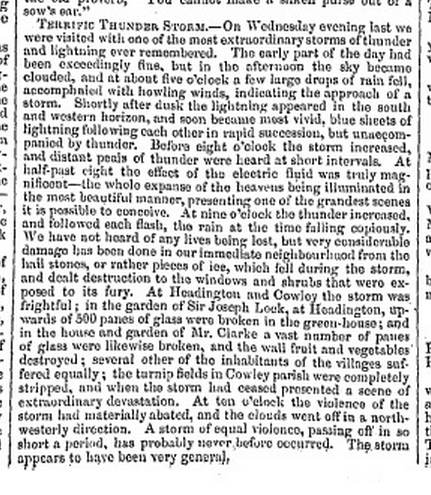

The following three extracts are taken from local newspapers, the year given in brackets.

“On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.” (1915)

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.” (1842)

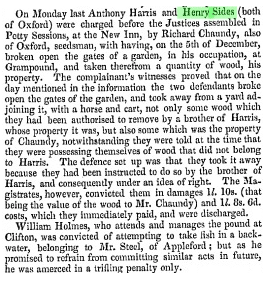

“Her mother got up and tried the door but it was locked by [the] witness when her father and mother came in. Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.” (1852)

The first concerns the death of my great-great-uncle Jonah Rogers; the second, a storm in Oxford in 1842, and the third, the murder of my great-great-great-grandmother in Jericho, Oxford in 1852.

But why have I chosen them?

It’s to do with the representations of silence in each of them and the way in which that silence is so arresting; augmenting as it does, our ability to empathise with the past. But how does it do this?

In all three quotes, the ‘revelation of silence’ comes after the ‘facts’:

“The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.”

“Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.”

“…the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon… but unaccompanied by thunder.”

Silence is not the subject of the texts, but a part which serves to illuminate the whole (which in the second extract is especially pertinent). It’s like the opening of a camera’s shutter; everything that came before it is condensed into a moment.

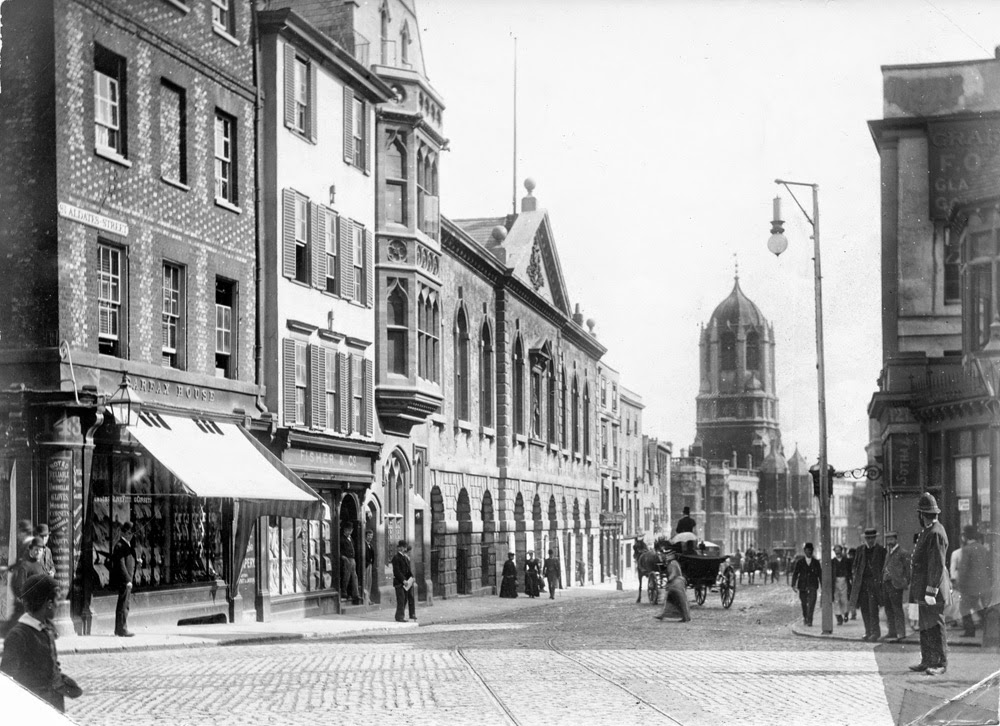

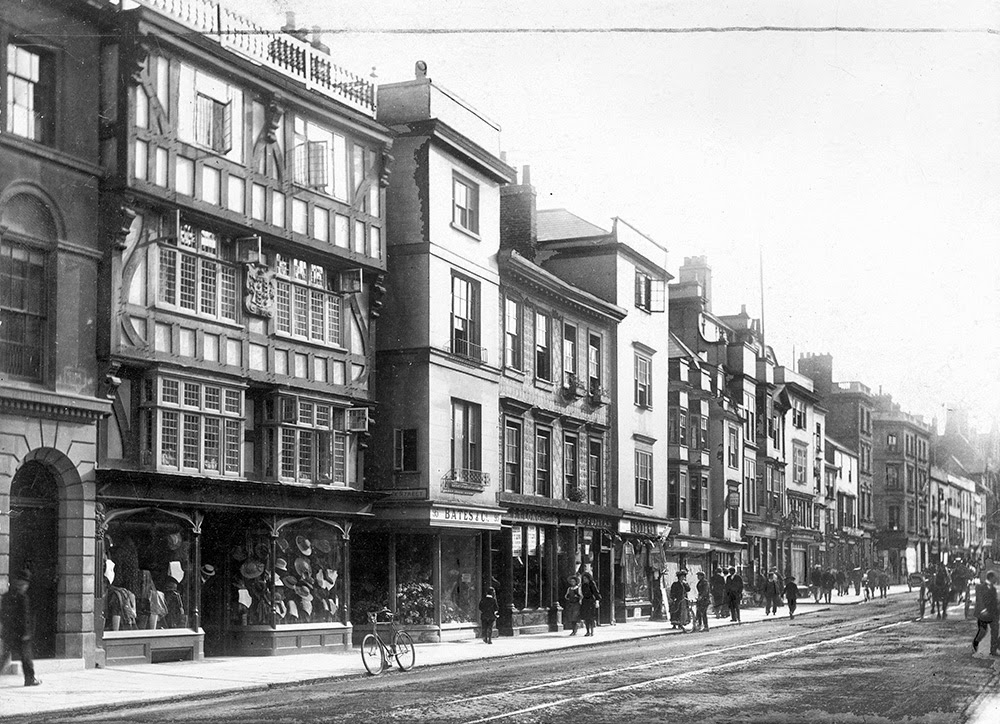

The above photograph, for example, was taken in Oxford in 1909. I’ve written about it before with regards to the bicycle parked at the edge of the road. The bicycle tells us that this scene is just a small part of a much wider one, one in which the man rode the bicycle up High Street with the intention, perhaps, of going to the shop, parked his bike and walked inside. We cannot see any of that of course, but it’s all contained in that moment.

A Victorian Storm

Whilst researching Jackson’s Oxford Journal, I randomly selected an edition from 1842 in which I found the following:

Following on from my last blog and my interest in the perception of time in the past as time passing I’m drawn to this piece which serves, I think, to illustrate the point.

For example, the first line:

“On Wednesday evening last we were visited with one of the most extraordinary storms of thunder and lightning ever remembered.”

Firstly, the words “Wednesday evening last,” pinpoints the storm in terms that are not ‘historical’. It’s not as if we’ve read in a book, “on September 7th 1842, a great storm hit the city.” Rather the event is located in time using a phrase we might use today. It locates the storm in relation to the present – even if that present is September 10th 1842 – and at once feels fresh and contemporary.

Secondly, the phrase “ever remembered,” reminds us, if you pardon the truism, that there was a time before this time. But whereas we know that before 1842 there was 1841 and so on, what this phrase describes is living memory. Again, if we were reading about the storm in terms of its being an historical one, we would know that everyone who experienced it was dead. Reading this article, they are very much alive. Not only that, but the whole of the nineteenth century – and perhaps a part of the eighteen is alive within them too.

It isn’t only this storm which lives within these words, but many others stretching back as far as the late 1700s.

The next description is something with which we have all experienced:

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.”

That lack of thunder is the punctum of this text. (Ironically, the last time I mentioned punctum in a blog was in an entry entitled ‘Silence‘ about the death of my great-great-uncle, Jonah Rogers.) All the sounds of Victorian Oxford, on that September night in 1842 are contained in that silence. Even within our imaginations, it would seem that the the absence of one sense, heightens all the others. We can sense the approaching storm, feel its presence on the horizon. We can see the muted colours of dusk, muted further still.

Then the thunder comes – “distant peals of thunder” as the writer puts it – which increase until by 9 o’clock, it accompanies every flash. This means of course that the storm was right above the city. The rain falls hard, and with it hail – or “pieces of ice,” which damage numerous properties and the turnip fields of Cowley. By 10 o’clock it was over.

One of the names mentioned in the piece is Sir Joseph Lock whose greenhouse was damaged to the tune of 500 panes of glass. An unpopular man, he built Bury Knowle House in 1800 (the gardens of which feature in another recent blog). Here in Headington, as it was in Cowley, the storm “was frightful” and we can imagine Mr Lock looking out the window of his house as the storm lashed his garden, his face, in the dark midsts of the past, illuminated for a moment by the lightning.

The Light from Bellatrix

Bellatrix, a star in the constellation of Orion, is a hot, blue giant some 240-250 light years away; let’s, for the sake of argument, call it 245. This would mean that the light from the star we see today, left in 1770 and has in that time been travelling at 186,000 miles per second. To put that in perspective, light can travel 7 times around the Earth in a single second.

|

| A view of Friar Bacon’s study, Oxford (1770) by John Malchair |

Such a speed and distance is pretty much beyond the scope of even the keenest imagination. It’s hard to comprehend for example that at the time of the French Revolution, the light from Bellatrix had already been travelling 19 years. That during the Great Exhibition, it was 71 years into its journey. And that at the start of the First World War it had been going for 144 years, still at a speed way beyond our comprehension.

And for another 100 years it has travelled; at 186,000 miles a second.

In contemplating the distance it has travelled, thinking in terms of major events doesn’t really help; after all, we don’t conceive of history in terms of seconds, and thinking of the speed of light outside a few seconds is difficult (669,600,000 miles per hour…?)

Recollecting events in my life however – from my earliest memories on a beach on the Isle of Wight, through nursery, primary school, the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, holidays in Swanage, Christmases, birthdays, sleep overs at my Nan and Grandad’s, church events, middle school, upper school, university, relationships, friendships, nights in the pub etc. – I can better imagine the passage of time, which, ironically, makes it more difficult to comprehend the distance light travels. I can do the same with regards my parents’ lives and, to some extent, my grandparents, but it becomes quite impossible beyond that.

Flicking through data on historic events of the last 245 years, the mind really begins to bubble:

1775 – American War of Independence

1780s – Start of the Industrial Revolution

1787 – First convicts sent to Australia

1796 – Jenner’s smallpox vaccination

1805 – Battle of Trafalgar

1829 – Peel establishes Police force

1832 – Great Reform Act

1837 – Queen Victoria ascends the throne

1851 – The Great Exhibition

1854-56 – The Crimean War

1859 – Origin of Species published

1863 – London Underground opens

1876 – Invention of the telephone

1887 – Invention of the gramophone

1901 – Death of Queen Victoria

1912 – The Titanic sinks

1914-18 – World War I

1920 – Demonstration of television

1927 – BBC is created

1939-45 – The Second World War

1952 – Queen Elizabeth II ascends the throne

1953 – Discovery of DNA

…and so on. But it’s not until I start flicking through newspapers that my mind starts to buckle.

There’s a website where one can browse historic newspapers, and in the case of Jackson’s Oxford Journal, everything published between 1800 and 1900 is available. For example:

From Saturday, April 8, 1882:

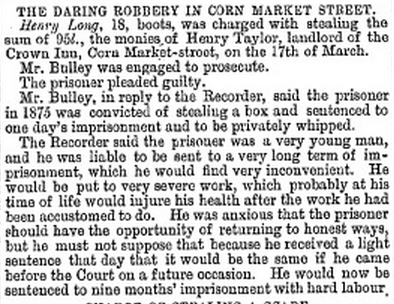

Our photons had been travelling 112 years when Henry Long stole £95 on 17th March 1882. We can imagine him now, a young man, at the Crown Inn, seizing the chance to grab the cash. We can hear the seconds ticking away, our photons moving 186,000 miles with every tick. We can imagine Henry’s heart beating… Then we cut to the Quarter Sessions where Henry was tried. We can hear his heart beating again as the verdict is read out, the photons still zipping through space far above. Then again we cut to April 8th and picture a woman sitting at home, a clock ticking on the mantelpiece. Beyond the window, the world goes about its business, as invisibly above, our Bellatrix light journeys towards us. The woman, sitting in the room, reads the paper and the story of Henry Long. It takes 48 seconds to read, in which time our photons have moved 8,928,000 miles closer to Earth…

Now we leap ahead 11 years to 1893, not far from the Crown Inn, where, in the blink of an eye, the scene below is caught on camera.

Perhaps someone in the photograph below – maybe the policeman – dimly recollects the story from all those years ago,

After the photograph’s been taken, life carries on. With every step the couple take below, the light which has travelled 123 years, moves on at the same, steady pace – the equivalent of 7 times around the world…

512-1

I remember how delighted I was when I discovered my 6 x great-grandfather Samuel Borton who ran the Dolphin Inn, Oxford, sometime during the 18th century. I felt a connection with him and, perhaps more importantly to the site of the inn he ran.

Then I discovered his father, Richard, who died (possibly in Holywell, Oxford where Samuel was born) in December 1714 when Samuel was just 8 years old. Imagining this man as a relative, as one might think of one’s grandparents or great-grandparents (if one was lucky enough to know them), I had to remind myself recently, that Richard Borton was just one of 512 people alive at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries from whom I’m directly descended.

To think of it another way. Imagine that in the year 2315, my direct descendent is born, then there are 511 people – including, of course, my wife – alive today who will also play a direct part in that person’s birth.

The Putting Green

When I was a child, we would often go as a family to Swanage for our holidays, usually accompanied by my Nan and Grandad. I have wonderful memories of those times; sudden storms on the beach, the amusement arcade (from which my Nan was asked to leave after a mild-mannered contretemps with the change machine), evening milkshakes in Fortes, preceded by putting on the putting green (pictured below).

|

| Putting in Swanage c1980 |

I loved putting and it was during a conversation in the office about Swanage that I wondered where exactly the putting green was. So often with memories, an event’s location slips anchor and drifts away, bumping up against other unassociated memories.

Using Google Streetview, I ‘went for a walk’ through the town centre, past the amusement arcade and what had been Fortes and, using the house in the background of the above photograph, arrived at what had been the putting green.

It was a putting green no more.

|

| Google Streetview showing the location of the putting green today |

It’s disconcerting, coming face to face with your past in the form of a ruin, or covered – as above – in tarmac. Suddenly, the way in which I visualise the far-distant past becomes the means by which I see my own.

I found the same on a visit to my first school, when I saw how the swimming pool had become an overgrown ruin.

The First Line?

Reading Clive James’ Poetry Notebook, I find myself a little better prepared to tackle the task of writing a poem; something I’ve wanted to do since the start of the New Year. I’ve made attempts in the past which I might publish in due course, but reading the Poetry Notebook I see where those attempts were lacking, as well as where, in small parts, they might be deemed to have worked.

What I have tended to do in those past efforts was to allow language to take over, to become a thing in itself; words for the sake of words. Now however, I want those words to work – to convey a specific meaning. In my art, I try and articulate that which is often beyond prose, things which should be well expressed in verse form.

But what will my subject be?

With the centenary of my great great uncle’s death near Ypres (8th May 1915) fast approaching, I thought I would look there for my subject, and remembering his obituary, I read it again and found my first line (the last line of the obituary):

All present standing in silence.

It’s a moving line which, having been isolated from its initial context creates a question. Who – or what – is present and standing in silence? I thought of soldiers standing for roll-call on a Parade ground. I thought of trees… but the language doesn’t allow for their lack of movement; yes they sway in the wind, but they do not leave and return as being present would suggest the ‘all’ have done. The words speak of people who have come together as a specific group. Of course, in its original context, the ‘all’ were the relatives mourning the death of one of their own:

The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.

The all is a family which, in the small church, isn’t all present. Instead there is a raw space which the silence seeks to fill; a physical silence eclipsing the wake of the church as it mines the depths of the family’s grief. Even from a distance of 100 years one can tune-in to that moment; catch as on shortwave radio their internal dialogues. And just as one can hear the “references to the death of Private Rogers” made by several members of the Church, those speeches are made formless as if heard underwater. For us it’s the distance of a century that does it. For the family it’s the distraction of cherished memories whose shapes are knife-sharp and remembered by their bodies.

Heavy Water Sleep (Poem)

I wouldn’t really call this a poem, but poem is the best word I can think of to describe what this is at present. Based on previous work, this text is derived from the first 19 pages of the book ‘Pilgrims of the Wild.’

[3]Outside a window stands silent, the surroundingcovered with heavy water sleep.

There is no sound and no movement

dropping through the

closed rude

earth. [4]a man

advancing with resolute step

But for the heavy steps,

there is silence [5]time Meanwhile

emerges

from a hole in the day before

and

pulls impatiently [6-7]at the window stops Outside

the so-lately deserted

Silence

the Extraordinary story

that lies behind this scene [8-9]The town dipped and scattered

White to a maze

Reduced though it might be,

this year was feeling choked

The farewell celebrations

were coming my way;

singing a low

whispering dirge [10]It was an arduous

empty return journey

A disastrous ground

barren, burnt out

tortured East so rumour had it

Much of my route lay through

unrecognisable miles

existing I passed on

wondering what lay ahead

sorrowfully living [11]still worrying

I met some old faces, who made

history in these parts;

a landmark in the

town [12-13]to get the feel of it again:

What did it all mean;

earlier days, undisturbed

kept alive by many old originals, waiting

days had passed into legend

respected by men

Time was rolling back

like a receding tide

adventurers, seeking the satisfaction

found in untouched territory

a strange, new, trail.

This place held memories

They had to stay [14]a journey was made

that covered miles

occupied years

there had been a girl, cultured,

talented [15]Most of my time

had been spent in solitude

I resented any infringement on my freedom

one of those unusual people [16]looking behind

These things were very dear to me

they were real people

who walked beside me;

features brought to my attention

one by one [17]I remember the hair

But far, far more

I discovered time

as it is now,

one with our own [18-19]born only too often

yards heavy in view

I began to feel with a pencil in hand

the body, marking the outline

where the wind shaped against her form

proceeding to cut

I stood in apprehensive silence

and viewed the slaughter

out of which was constructed

the word best fitting

the impression which I gained

we had considered sending them back,

though we never did;

lonely at times vaguely uncomfortable

in those days the weather singing winter

through the window

sunsets were often good to look at

we arose before daylight and travelled all night

they had waited patiently, wishing

She was, she said becoming jealous

blind hatred could not see

and dreamed lines of traps

A ‘detonation in the shadows’

I’ve often thought of history as being like a series of rooms or interiors in which everyday life is played out and conversations turn upon the news – the now historic events – of the day. In contemplating the past, I’ve often turned to a quote from George Lukács who said that ‘the “world-historical individual” must never be the protagonist of the historical novel, but only viewed from afar, by the average or mediocre witness.’ When seeking to empathise with those who lived long ago, I have tried to re-see – and re-feel – historic events in terms of their everydayness, or their nowness; to see the events as a backdrop to the everyday world.

One can imagine a husband and wife sitting down to dinner, talking about the day; what such-and-such a person said about such-and-such another (names which we might find today clinging on to wearied graves, or tangled up in inky knots as unintelligible on the page as death itself); a folded newspaper rests on the arm of a chair, in which the news begins its slow absorption into history. A clock ticks on the mantelpiece.

Last week I read Patrick McGuinness’ memoir, ‘Other People’s Countries’, and came upon this rather beautiful passage:

“When I’m asked about events in my childhood, about my childhood at all, I think mostly of rooms. I think of places, with walls and windows and doors. To remake that childhood (to remake myself) I’d need to build a house made of all the rooms in which the things and the nothings that went into me happened. And plenty of nothing happened too: it’s The Great Indoors for me every time. This house of mine. this house of mind, would be like a sort of Rubik’s cube, but without any single correct alignment or order: the rooms would be continuous, contiguous, they could he shuffled and moved about, so that its ground plan would be always changing. Just as they build for earthquakes or hurricanes, creating buildings that have some give in them, that can sway with the wind or sit on stilts in water and marshland, that can shake to their foundations but still absorb the movement, so the rooms in the house of a remembered childhood take on the shocks and aftershocks of adult life, those amnesiac ripples that spread their blankness along the past. Trying to remember is itself a shock, a kind of detonation in the shadows, like dropping a stone into the silt at the bottom of a pond: the water that had seemed clear is now turbid (that’s the first time I’ve ever used that word) and enswirled.”

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- …

- 32

- Next Page »