Schopenhauer: ‘The task of art is to turn tears into knowledge’.

Kinaesthetic Empathy

The following text ‘What is Kinaesthetic Empathy’ is taken from the Watching Dance website. Although I’m not an afficionado of Contemporary Dance, I’ve become interested in how aspects of movement and general agency have started to appear in relation to parts of my work and research.

“Spectators of dance experience kinesthetic empathy when, even while sitting still, they feel they are participating in the movements they observe, and experience related feelings and ideas. As dance scholar Ann Daly has argued:‘Dance, although it has a visual component, is fundamentally a kinesthetic art whose apperception is grounded not just in the eye but in the entire body’ (Daly 2002).Spectators can ‘internally simulate’ movement sensations of ‘speed, effort, and changing body configuration’ (Hagendoorn 2004).An important source for the concept of kinesthetic empathy is Theodor Lipps’ theory of ‘Einfühlung’. Lipps (1851-1914) argued that when observing a body in motion, such as an acrobat, spectators could experience an ‘inner mimesis’, where they felt as if they were enacting the actions they were observing.This shared dynamism of subject and object implied the notion of virtual, or imaginary movement.Kinesthetic empathy and related concepts took on particular relevance in the context of modernism, which emphasized the idea that receivers should respond directly to the medium of a work of art (eg. movement rhythms) rather than to a storyline or a subject.In the US, Lipps’ ideas were taken up and developed by the influential dance critic John Martin (1893–1985), who championed the dance of Mary Wigman and Martha Graham. Martin argued that what he variously called the spectator’s ‘inner mimicry’, ‘kinesthetic sympathy’ or ‘metakinesis’ was a motor experience which left traces – ‘paths’ – closely associated with emotions in the neuromuscular system. Sensory experience could have the effect of ‘reviving memories of previous experiences over the same neuromuscular paths’, and also of ‘making movements or preparations for movement’ (Martin 1939).”

The following is a quote from Christopher Tilley:

“If writing solidifies or objectifies speech into a material medium, a text which can be read and interpreted, an analogy can be drawn between a pedestrian speech act and its inscription or writing on the ground in the form of the path or track.”

What I have been researching as part of my work could be described as Kinaesthetic Empathy whereby a person’s being in a place and his/her movement through or around that place is a means of ‘reading’ the ‘writing’ laid on the ground by what Tilley calls the ‘pedestrian speech act’.

Totes Meer

I was watching The Culture Show last night and during a piece on a Paul Nash exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery I was struck by the following painting, Totes Meer which can be seen below.

It shows a heap of German planes – those brought down over England, ready to be sorted so the metal could be salvaged. For Nash, it was a scene to inspire Patriotism, but what interested me – at least initisally – was the fact this scrap heap had been in Cowley, not far from where I once lived.

I am of course interested in the past, the wreckage of the past if you like, and how we can salvage parts to be reused in the present day, so therefore this painting has a great deal of interest for me; not only because of that but because of the scrapheap in Cowley.

Stories

In his excellent book, ‘The Past is a Foreign Country’, David Lowenthal writes:

“Among the Swahili, the deceased who remain alive in the memory of others are called the ‘living-dead’; they become completely dead only when the last to have known them are gone.”

Having read this, I began to think about Henry Jones, my great-great-grandfather who took his own life in Cefn-y-Crib in 1889. For all intents and purposes, he had, until I (and another distant relative) had begun to research him, been ‘completely dead’ in that anyone with a knowledge of who he was would also have passed away. For many years therefore, he would have existed as a name, inscribed on his grave or recorded in various documents such as census returns. He would have been, apparently, nothing more than that.

Now however, he is part of my family tree, ‘reconnected’ – albeit abstractly – to his own loved ones and those who came both before and after he lived. But a list of names, connected or otherwise is only a part of the story. As Tim Ingold writes, in his book ‘Lines – a Brief History‘:

“The consanguineal line is not a thread or a trace but a connector.”

The line connecting Henry Jones to his forebears and descendants tells us nothing about him. As Ingold explains; ‘Reading the [genealogical] chart, is a matter not of following a storyline but of reconstructing a plot.’ What I want, as far as is possible, is the story, the narrative as it was written at the time.

As I wrote in my essay ‘What is History?‘:

“Human beings [Ingold writes] also leave reductive traces in the landscape, through frequent movement along the same route… The word writing originally referred to incisive trace-making of this kind.’ By walking and leaving our reductive traces on the ground therefore… we could be said to be writing or drawing ourselves upon the landscape – writing or drawing our own history.”

It was only when I visited Hafodyrynys in May 2008 that Henry Jones became – for want of an expression better suited to the 21st century – in the words of the Swahili, ‘living-dead’ again. It was only then, as I walked around the village where Henry Jones lived, walking the same roads and pathways, that I began to read – as far as was possible – a part of his story. I knew the dates of his birth and death (I’ve since learned of his suicide) but these are plot points. Only when retold as part of the story do they start to make an impact, and that story can only be read in the places where he walked.

As I walked, I felt as if I was both recording my own story on the roads and pathways around Cefn-y-Crib, whilst reading that of my ancestors, in particular my paternal grandmother, who lived as a child nearby in Hafodyrynys and who passed away a few months after my visit.

A quote from Christopher Tilley’s ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’ illustrates this point:

“The body carries time into the experience of place and landscape. Any moment of lived experience is thus orientated by and toward the past, a fusion of the two. Past and and present fold in upon each other. The past influences the present and the present rearticulates the past.”

As we walked (I visited with my dad and girlfriend, Monika), we would phone her up and tell her where we were, and I couldn’t help but feel that we were walking directly within her memories. Time it seemed had collapsed for a while.

As I wrote as part of an investigation in the Old London Road at Shotover:

“Thinking about it now one can take that analogy and think of it [the road] instead as piece of tape which runs and runs and runs and which every step upon it is like the recording head changing the ground, changing the particles on the tape just a little. And just as we record when we walk so we also play, play the ground which passes beneath our feet. We can hear very distantly the thoughts which came before us.”

So how do we read or hear these ‘stories’, written into the ground and the landscape so many years before we were even born? One clue comes in the following extract from Christopher Tilley’s book, ‘The Materiality of Stones, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology‘.

“The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would he impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects. Dillon comments: The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

If we take the analogy of the mirror for a moment and return again to my essay ‘What is History?‘:

“In a famous definition of the Metaphysical poets (a group of 17th century British poets including John Donne), Georg Lukács, a Hungarian philosopher and literary critic, described their common trait of ‘looking beyond the palpable’ whilst ‘attempting to erase one’s own image from the mirror in front so that it should reflect the not-now and not-here…’

Just as the trees function as ‘Other’ therefore, so must the sun, the stars, the clouds, hills, mountains, the sea, rivers and so on. Where we are in the world, where we stand or walk, which direction we are facing are all significant features in this respect. We are what we are because of where we are at a given moment. We exist in relation to [these ‘Others’] and are at any given moment defined by them….

Last year I visited Hafodyrynys in Wales, the village where my grandmother grew up. Whilst standing on top of the hill where she played as a child and across which her father walked on his way to work in the mines at Llanhilleth, I looked and saw a view I knew he would have seen. I found it strange to think that a hundred years ago he would have stood there, just where I was, at a time when I did not exist. A hundred years on and I was there when he did not exist. And yet we shared something in that view. We had both for a time been defined by it. It was as if the view could still recall him and even though it was new to me, that I was nonetheless familiar.”

We are defined by the world around us and as such we might be said to be remembered by that world. But of course over time the world changes and where things disappear, so do, to some extent, memories. We therefore have to fill in the gaps. I once wrote something about this during a residency at OVADA in Oxford in 2007.

“In the film, the visitors to the Park are shown an animated film, which explains how the Park’s scientists created the dinosaurs. DNA, they explain, is extracted from mosquitoes trapped in amber and where there are gaps in the code sequence, so the gaps are filled with the DNA of frogs; the past is in effect brought back to life with fragments of the past and parts of the modern, living world. This ‘filling in the gaps’ is exactly what I have done throughout my life when trying to imagine the past, particularly the past of the city in which I live.”

I appreciate that my metaphors are beginning to stack up a little. However, where we can fill in the gaps with our own experience is where we can begin to see the past as it was when it was the present.

No Man is an Island

I have written a great deal about how I perceive the past and how I use objects and the landscape to find ways back to times before I was born. In my text ‘What is History‘ I conclude with the following paragraph.

“History, as we have seen, [might be described as] an individual’s progression through life, an interaction between the present and the past. It follows, having seen how the material or psychical existence of things extends much further back than their creation that history spanning a period of time greater than an individual’s lifetime is like a knotted string comprising individual fragments; fragments within which – in the words of Henri Bortoft – the whole is immanent. The whole history of all that’s gone before is imminent in every one of its parts; those parts being the individual.”

I was reminded as I read this paragraph – and in particular the last line – of the poet John Donne and the following words taken from his XVII Meditation:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Having read this, I thought about some of the work I’ve been making for my forthcoming exhibition in Nottingham, Mine the Mountain. Two pieces are maps of invented landscapes, one of which (the first shown below) is based directly on a map I created as a child, the other based on the outline of Belzec Death Camp as seen in an aerial view of 1944.

The Past is a Foreign Country, 2010

The first map, as I have said, is a contemporary reproduction of one I made as a child. It’s therefore essentially a map of an individual – of me, as I was at the time. It is a place that, although imagined, was real nonetheless, one based on fragments of my memory and my perception of the distant past.

Having been to Wales (in 2008) and imagined all my distant forebears walking the various tracks and roads around the village where my grandmother grew up, I realised how I was very much a part of those places and they in turn were part of who I was. I had existed – at least potentially – in those places long before I was born. All those roads, paths and trackways led in the ‘end’ to me. Of course that sounds a rather egocentric way of perceiving the world and its history, but then I’m not suggesting that I am the only intended outcome. Just as my invented world – my map of me – was made of all those bits of the past I loved to imagine as a child (the untouched forests, the unpolluted rivers and streams) so I can see how this foreshadowed my current thoughts on history; how I am indeed (as we all are) a place, one made of all those places in which my ancestors walked, lived and died.

A quote from a source which is of huge importance to me and my work (Christopher Tilley’s ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’.)

“Lived bodies belong to places and help to constitute them so much so that the person can become the place (Gaffin 1996). The body is the medium through which we know place. Places constitute bodies, and vice versa, and bodies and places constitute landscapes. Places gather together persons, memories, structures, histories, myths and symbols.”

Alongside the second map I will be showing a piece of text taken from the diary of Rutka Laskier describing what appears to be an imaginary landscape, though one perhaps based on memories of family holidays to Zakopane, Poland. She was a child when she died in the Holocaust and by putting the two maps together, I want to reflect on the numbers of children who perished, as well as illustrating how within each child – within everyone – the whole of humanity is immanent.

John Donne’s words serve to illustrate this sentiment further still. No man, woman or child is an island. So whilst I have created two maps of individuals, through Donne’s words we can see how these islands comprise pieces of everybody else.

If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less.

Fragment

I’ve spent the last day or so working on a new composition which will form part of an art installation based around a fragment of mediaeval pottery… (all will be revealed in due course).

Anyway, for now, here is a very short part of what I’ve written and recorded. By the way, the vinyl crackle is important as regards the visual element.

More Images of Vandalised Labels

The Woods, Breathing: Vandalism

When I told people that I would be installing almost 200 markers in Shotover Woods as part of a Holocaust Memorial Day project (The Woods, Breathing), many said the markers wouldn’t stay there long. I however, believing that people – even if they didn’t like the work – would at least respect it, put them in anyway. Besides, I believed the work was powerful, using the act of walking through woods as a means of identifying in a very small way with those who suffered during the Holocaust. And, furthermore, I believe anything which attempts to engage people with something like the Holocaust is worth pursuing. However, within one hour of completing the installation, 3 had already been stolen and over the coming days, the labels were turning up in small piles along with the stands. Clearly there were two different types of vandals at work; those who stole or threw the stands into the undergrowth, and those who were at least a little more considerate. I could almost imagine these methodical vandals as they made their small piles, saying to themselves (and indeed to me) “not here thank you.”

I have made work like this before in public spaces in the city centre. In one work (‘Murder‘) I installed 200 stands in a cemetery in Jericho, a place frequented by drinkers and rough sleepers. Not one of the stands was stolen and only one label was lost. If anything, from my experience, those we might often think of as being on the ‘fringes’ of society are often the most interested. Sadly the same can’t be said of others.

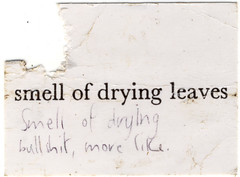

Today I went up to Shotover to take what was left away and found that since my last visit a great many more of the stands had been taken; almost 80 out of the 198 had been removed (at £5 each this is quite a loss) . Furthermore, someone had taken the time to scrawl messages onto some of the labels having clearly not bothered to learn what the work was about.

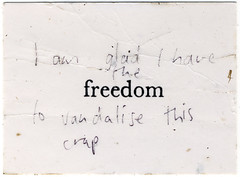

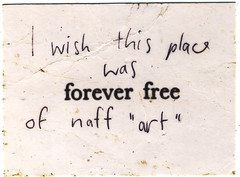

This vandalism was not I believe anything to do with its theme (the Holocaust) but rather an expression of petty narrow-mindedness. Someone who enjoyed the woods, someone who obviously walks through them regularly objected to ‘their walk’ being changed these last few days. One label they defaced is quite revealing:

This work is all about freedom; something denied to so many not only during the Holocaust but in countless times and places, both before and since. Yet all this individual can do with his or her freedom is scrawl remarks and obscenities, to deface a work which aims to remember those for whom freedom was denied as was, in the end, the right to life itself.

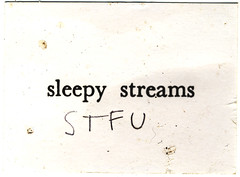

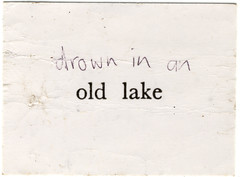

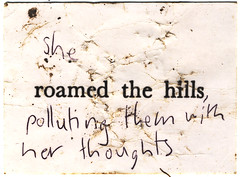

Looking at the vandalism by this particular individual, it’s clear they didn’t understand what the work was about. They seemed to think that I was a girl…

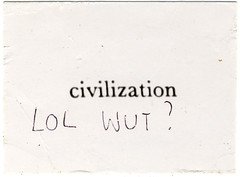

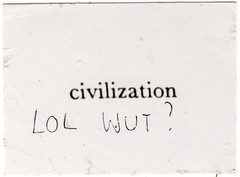

…who’d written nice words about the wood. The word civilization on one of the labels and what they wrote beneath is testament to this. What they wrote is also somewhat ironic.

The Woods, Breathing

I was on the radio this morning to talk about my forthcoming installation at Shotover Country Park.

Details of the installation can be found by clicking on the image below.

Weymouth

Yesterday I went to Weymouth to look at some deckchairs for use in a number of installations. One such installation I’ve been considering centres around the D-Day landings – I won’t go into the details of what it will entail but I was amazed as I was shown around the front to discover that Weymouth played a pivotal role in the landings themselevs, in that it was from the harbour that many of the men who took part in the invasion left. The coincidence convinced me that this was the place – the only place – where the work could be installed.

On the front is a memorial to the men who took part in the D-Day landings.

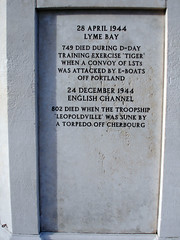

Around the base are the following inscriptions.

28 April 1944

Lyme Bay

749 Died during D-Day training exercise ‘Tiger’ when a convoy of LSTs was attacked by E-Boats off Portland.

24 December 1944

English Channel

802 Died when the troopship ‘Leopoldville’ was sunk by a torpedo off Cherbourg.

11th October 2002

Prior to 6th June 1944 the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions of the Army of the United States of America depended heavily on men and equipment of the Landing Craft Assault (LCA) Flotillas during training and while developing special assault-techniques on D-Day, these same men of the Royal Navy demonstrated the finest traditions of their service through their courage, steadfastness, and devotion to duty. The successes of their assaults at Pointe du Hoc and the Omaha beaches of Dog Green, Red and White were made possible through their skills and bravery. All World War II Rangers are proud to be associated with the veterans of the LCA Flotillas of the Royal Navy and remain grateful to them, and their vessels both large and small.

We remember your Nation’s sacrifice

60th anniversary

D-Day

June 2004

6 June 1944

Omaha Beach, France

Showing courage and endurance beyond belief 3000 died on D-Day while fighting to secure the beachhead and strategic Pointe du Hoc, spearheading the invasion of Normandy. As this millennium closes we commit this memory to history June 1999.

Further along the beach are more war memorials.

A.I.F.

In memory of Anzac Volunteer Troops who after action at Gallipoli in 1915 passed through hospitals and training camps in Dorset.

As a child, I often went with my family on holiday to the Dorset coast, either to Weymouth or the surrounding areas, and even though my experiences were – it goes without saying – utterly different to those of the men who left Weymouth for France, nevertheless, there is something about these experiences residing in the past as memories which allows me to, in some small way, access the past before I was born. The past (and in particular the distant past) is often imbued with a sense of the exotic – a word which is of course as far removed from the reality endured by the men who fought and died during D-Day as you can get. This ‘exotic’ quality is more akin to the nostalgia we often feel when contemplating our own memories. There is a sensuousness to memories which we experience without recourse to our senses. We see, hear, smell, touch and taste memories internally; we can see them with our eyes closed. Only by being in the place where they happened can we begin to experience them as things which happened in what was then the present. It’s almost as if they are grounded.

Standing in Weymouth and looking out at the cliffs, feeling the wind, hearing the gulls and the waves, I could get a greater sense not only of my own memories, but those of a time when I was not even born. The men left Weymouth and who died on the beaches of Normandy would have known the same feel of the wind, the same sound of the waves – they would have seen the very same cliffs. We can never know what it was like to be in their shoes, but by understanding and observing the present we can at least ground the memories in reality.

Looking at some recent work I’ve done with some of my old holiday snapshots, I can see in light of my visit to Weymouth how they have become more meaningful. The image below is a collage of all the parts of those holiday snaps from which the people have been removed.

The Place That’s Always There (2009).

Free Writing: The Pliosaur

Free Writing*

8 Minutes

Think of the sea. Think of all the times to have seen it with your own eyes. Listen to its sound. Concentrate on the rhythm of the waves; the in, the out, the waves falling and then receding. Think of the moon dictating the tides and the sun which warms your skin as you sit there on the sand. Watch the waves come like creases, to fall in froth on the sand, grabbing at the shingle. Listen to yourself breathing, in and out, in and out and let the waves and your breath come together. As you breathe in the waves fall back, as you breathe out the next one crashes on the sand. In and out. Look at the colour of the water. Imagine the water is clear. You can see everything beneath, the stones, the seaweed. You can see the sun’s reflection on the surface, lots of tiny diamonds of light. You look up at the sky. You see just the vast expanse of blue and perhaps a few clouds which float innocuously. As you breathe and as the waves crash upon the beach in time to your breathing, watch the clouds float above, changing almost imperceptibly into what they will next become. Watch the strands of clouds high above them and see the sun too bright to look upon directly. See the line of the horizon, see the rocks, the cliffs upon which the wind agitates the grasses. Then take your mind out with the waves and into the water, across the waves and away from the sound of the waves. There are no waves now, just the wind and the sun, the water and the disatnce. Now go beneath the clear water and see the Pliosaur. This unimaginable monster, seventeen metres long, swimming like a shark. You can feel the water, you can recall what it’s like but you are not in the place where the Pliosaur swims. No-one is in this place and even the earliest ancestor of modern man will have to wait nearly 150 million years before they arrive, before they will at the edges of time be able to take a photograph of the sea. That in which the Pliosaur no longer swims. look at the waves, listen to the waves and think of the fossil of the Pliosaur.

* writing without stopping; read more.

Creation Time

Flying back from Luxembourg I continued reading Richard Dawkins’ wonderful book The Blind Watchmaker. As someone who has taken Evolutionary theory for granted, I’ve realised since starting this book how little I really knew and how much I’ve subsequently learned. I’ve also begun thinking more seriously about religion and in particular Creationism. Creation myths are beautiful stories – I’ve always thought that – but when they are posited as theories and fact, one can only look on with some degree of despair. Reading this book has deepened that sense within me for Evolution and Natural Selection is not only an astounding theory but a beautiful fact of life.

I’ve often wondered what it is that Creationists and other religious persons object to when they insist that Evolution isn’t true – when clearly it is- and I think it can be summed up in one word: Time. We all find it very hard to conceive of Geological Time, that vast, incomprehensible span which makes each of us, as individuals, appear absurdly insignificant. We can easily imagine a century and even a millennium. We might if we have good imaginations contemplate the ice-age. But when we start considering the emergence of man 2 million years ago – let alone the Dinosaurs at 65 million – then we really start to struggle. Trying to imagine the age of the earth and we start gasping like a fish out of water.

As Professor Dawkins explains, we are not built to conceive of such spans of time such is why mutation (such as the fish leaving the water to walk upon the land) appears to us as absurd as a fish on a bicycle. We tend to ‘see’ these changes in our mind’s eye as happening within a length of time relative to our own brief lives. We see a fish suddenly sprout legs and leap onto land as if it were one in a garden pond taking a stroll on the lawn. Clearly it wasn’t like that. The length of time that was required for this process to occur is simply beyond our comprehension.

Before science began making strides out into the Universe and into ourselves, no-one could imagine the Earth and the Universe were so old. It made perfect sense to give them – or at least the Earth – an age within the grasp of human comprehension. It could be argued that the age of the Earth – given as a few thousand years – was arrived at, because it was at the limits of what the human mind could reasonably conceive. But what about the after life? Surely people could happily imagine eternity as a span beyond the supposed age of the earth? Well, yes, perhaps they could. But the difference between the eternity of life after death as opposed to the comparative eternity of time before life is stark. In the former, the individual being exists – one assumes as a soul, but in the latter the individual being has to contend with non-existence.

One of the most beautiful descriptions of the vastness of time comes from the seventeenth century and was written by Sir Thomas Browne in his book Urne Burial.

“We whose generations are ordained in this setting part of time, are providentially taken off from such imaginations. And being necessitated to eye the remaining particle of futurity, are naturally constituted unto thoughts of the next world, and cannot excusably decline the consideration of that duration, which maketh Pyramids pillars of snow, and all that’s past a moment.”

It was one thing to conceive of a span of time which made ‘all that’s past a moment,’ as being time of which one would somehow be aware or a part, but to conceive of the same span of time before one’s birth was – and is for many – quite impossible. My aunt once said to me ‘you have to believe in something.’ If you take that argument and turn it around it becomes quite telling: you can’t believe in nothing. Is religion therefore a consequence of a fear of nothing? And is a fear of nothing a fear of time?

Work in Progress

Re-count

I have been reminded by Monika that I really liked an Australian piece shown elsewhere in the city. By Healy and Cordeiro, it comprised thousands of used video cassettes (195,774 according to documentation) arranged in a large block like a kind of tomb on the outside of which a number of the labels (some printed, some handwritten) were visible.

The vast block, displayed in an ecclesiastic setting became a kind of sepulchre in which the recent past was buried. The titles on the outside became like names revealing only a little of what was hidden inside, information which would take – again according to documentation – over 66 years to view. So, Australia was in this respect, excellent.

53rd Venice Biennale

In terms of individual participants showing at the Biennale, I was taken with quite a number of works including Nathalie Djurberg’s disturbing video/sculpture installation described in the catalogue as a surrealistic Garden of Eden, Hans-Peter Feldmann’s beautiful Schattenspiel (Shadow Play), Simon Starling’s Willhelm Noack oHG and Chu Yun’s Constellation. There were numerous others too, including, perhaps most notably Mona Hatoum who showed at a so-called ‘collateral event’ in the Querini Stampalia.

But just as there are a small number of winners so there’s an inverse number of losers – crap to you and me. The winner of the wooden spoon however has to be Switzerland’s entry (I’m fighting against the desire to write Bang-a-Bang-a-Bang or such like silly song title and have in a sense already failed). The work explained – or rather the blurb did – that ‘drawing is a movement of sight, of the nuanced shifts and deviations that attract undirected attention to objects and dream figments that are never really concretized’ and from that codswallop you might agree the curators or whosoever wrote the guff for each piece should also claim a piece of the booby-prize. Other notable rubbish included Australia (who were also rubbish two years ago) and Germany (who were my wooden spoon winners at the last Biennale and who for this year’s effort drew on the talents of British Artist Liam Gillick (?) who managed to make a trip to IKEA look interesting – by the way I read that Gillick travelled for more than a year, ‘researching and developing his project for the German pavilion in a continuous dialogue with curator Nicolaus Schafhausen’ – quite how he arrived at making some dull cupboards escapes me). Israel’s entry was terrible and Norway’s too (definitely nil point). There were other notable wastes of space but I can’t be bothered to waste any space upon them.

One of the biggest disappointments for me however was the British entry from Steve McQueen, whose film Giardini was, well, boring. Certainly it contained some beautiful shots and was an interesting idea, but at 30 minutes it was just too long. There was also the fact that one had to view it at a certain time, that viewers were asked to arrive 10 minutes before the show which built up expectations to such a level the film almost had to fail. After a few minutes we were already shuffling in our seats, a few more minutes – when the dogs came again and sniffed around in a manner straight from a Peter Greenway film (no slight on that director intended) – and we were checking our watches. As a piece one could view at leisure, walking in and out at whatever time suited, it probably would have worked, but treating it like a film turned it I’m afraid into a very dull affair. As I don’t have any pictures of these less-than-inspiring works here is a picture of very-inspiring Venice.

What I really loathe are those pieces where the artist assembles tons of stuff in a room or space with which the viewer is asked to ‘create a narrative’ or not as the case may be. There are a few exceptions where this type of work is successful, but by and large it irritates the hell out of me. So Haegue Yang and Pascale Marthine Tayou, pack it in now.

But what about the winners..?

For me, Peter Forgacs’ Col Tempo was exceptional, giving history a human face. Taking archive footage from the Wastl project, he showed how people in the past, who lived in times of trauma were just like people today. It sounds a pretty obvious thing to say but often when we think about the past we tend not to see individuals as such, but rather numbers and tropes. Ironically, the footage Forgacs used was originally concerned with anything but the individual, rather Dr Josef Wastl, head of the Department of Anthropology at the Museum of Natural History in Vienna, put on an exhibition which attempted to present to the public ‘the characteristic physical features’ and ‘mental traits’ of the Jews. What we see when looking at the images however are individuals just like us today.

Poland’s Krzysztof Wodiczko examined the issue of immigration. The Guests of the title were shown as shadow-figures outside the space in which we as onlookers (or out-lookers) were standing. We saw them without faces, without distinguishable characteristics, save for their voices which accompanied the work Nevertheless, in their outlines we could recognise the people we see all around us, the way they move, the way they stand and taken together with Forgacs’ work, it was indeed a powerful piece (by the way Poland won it for me two years ago).

Another powerful pieces came via Teresa Margolles who showed her work in the Mexican ‘Pavilion’. Her installation (and action) What Else Could We Talk About? took the country’s endemic violence and brought it into the Palazzo Rota-Ivancich. The Palazzo is a decaying structure which is nonetheless quite beautiful. The original (or at least very old) decor is still visible – faded wallpaper with patches where paintings (perhaps portraits given their shape) once hung. It was almost enough just to be in the building. Each room contained an incongruous mop and plastic bucket in which we learned blood collected from sites of killings in Mexico was mixed with water and used to wash down floors over which we were walking. In every room therefore one could sense quite palpably the echoes of missing people – those who’d lived and died in the city over the course of the Palazzo’s existence and those who lived and died in the present albeit thousands of miles away. There was a sense of the past and distance in the present being synonymous. There were also paintings again made from blood collected at the sites of executions in Mexico. Each painting, hanging like a blanket, resembled a modern-day Turin Shroud and I found myself being asked to believe, not in a life that could be known only through death, but individual deaths (and many of them) happening in the midst of life today.

Estonia’s entry examined in part the power of symbols and in particular the replica of a statue which had once stood in the capital Talinn. The statue (the replica of which looked quite kitsch in the gallery) marked the grave of Red Army soldiers from 1947 until its removal in a post-communist Estonia. For most Estonians the statue was a symbol of Soviet oppression, for many ethnic Russians it symbolised victory over Nazism. The artist, Kristina Norman placed the replica where the original statue had stood and documented the furore that followed with the police taking both her and the statue away.

The Portuguese artists Joao Maria Gusmao and Pedro Paivia showed a series of video projections in a piece entitled Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air. Each piece appeared to have been shot with a high speed camera, revealing in slow motion clear details of fire, water etc. But the appearance of each projection was that of a 1970s snapshot. The texture and quality of the projections reminded me of my own holiday photographs and in particular some work I’ve been doing on their hidden details.

And finally Luxembourg. Another video installation tucked away in a backstreet in which the artists Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert reflected on the divide between Africa and Europe, evoking according to the catalogue issues of difference and immigration. What I liked about the piece was the dialogue created between the various projections as seen through open doorways between the rooms. The image of a fly struggling in a spider’s web and that of a man standing still in a street but clearly lost in an alien world was particularly striking – one could sense via the other image his internal struggle.

All in all the Biennale served up the usual mix of both the sublime and the ridiculous. Much of it – especially in the Arsenale (now a much bigger site) was pretty lame, but then any work would struggle in such a massive space, vying for attention like an antique thimble in a flea-market. Certainly the use of spaces outside the sites of the Giardini and Arsenale tended to make for more interesting work, but one could argue that when in a place like Venice every space and every part of every space is interesting, whether home to art or not.

Echo

Last week I installed a temporary artwork in St. Giles, Oxford entitled Echo. The piece comprised approximately 200 photographs of individuals isolated from group shots of the fair taken in 1908, 1913 and 1914. The date of the exhibition, Wednesday 9th September was important in that it was the day after St. Giles’ Fair was taken down, and the ‘space’ left in its wake (the fair was up for two days and filled the entire street) helped frame the fact that all those people shown in the exhibition, who had once stood in the same street, had, like the fair, gone. I was interested in the boundary between existence and non-existence, the impossiblity – within the human mind – of death as nothing and forever. What I hoped the photographs conveyed was the importance of having been.

The installation required grass in order that I could place the markers in the ground and the War Memorial in St. Giles was the only viable option. What was particularly interesting was how the location altered the meaning of the work in that one couldn’t help identify the people with the memorial and in particular those who fell in World War One. Given that some of the men pictured in the photographs almost certainly went to war and may well have lost their lives, so the work took on a new and poignant dimension. Many of the women would have lost husbands, brothers, fathers, uncles and so on.

Click here to read more about this exhibition.

Ersilia

As my website has grown and groaned beneath its mass of words and pictures, I have in the last couple of months put together a digest of my work in a magazine called Ersilia which is available to download from my website.

The title comes from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities in which he describes the city of Ersilia:

“In Ersilia, to establish the relationships that sustain the city’s life, the inhabitants stretch strings from the corners of the houses, white or black or gray or black-and-white according to whether they mark a relationship of blood, of trade, authority, agency. When the strings become so numerous that you can no longer pass among them, the inhabitants leave: the houses are dismantled; only the strings and their supports remain.

From a mountainside, camping with their household goods, Ersilia’s refugees look at the labyrinth of taut strings and poles that rise in the plain. That is the city of Ersilia still, and they are nothing. They rebuild Ersilia elsewhere. They weave a similar pattern of strings which they would like to be more complex and at the same time more regular than the other. Then they abandon it and take themselves and their houses still farther away.

Thus, when traveling in the territory of Ersilia, you come upon the ruins of the abandoned cities, without the walls which do not last, without the bones of the dead which the wind rolls away: spiderwebs of intricate relationships seeking a form.”

Chance as a Draughtsman

I have recently been reading Richard Dawkins’ fantastic book ‘The Blind Watchmaker’ and was struck by the following passage as regards the work I’ve been doing over the past few years:

“We have seen that living things are too improbable and too beautifully ‘designed’ to have come into existence by chance. How, then, did they come into existence? The answer, Darwin’s answer, is by gradual, step by-step transformations from simple beginnings, from primordial entities sufficiently simple to have come into existence by chance. Each successive change in the gradual evolutionary process was simple enough, relative to its predecessor, to have arisen by chance. But the whole sequence of cumulative steps constitutes anything but a chance process, when you consider the complexity of the final end-product relative to the original starting point. The cumulative process is directed by nonrandom survival. The purpose of this chapter is to demonstrate the power of this cumulative selection as a fundamentally nonrandom process.”

The first sentence in this passage struck a chord with me as regards thoughts I’ve had on the sheer unlikelihood of my ever being born – my entire existence. When one considers that in order for us as the individuals we are to be born as we were, everything every one of our ancestors did had to be done exactly as it was, the mind implodes beneath the weight of our sheer improbability. Indeed as individuals we are teetering on the cusp of impossiblity; it’s almost as if we have been designed to be who we are (which of course is not the case). In many respects this problem of coming to terms with our individual existences in light of what amounts to seemingly random acts on the part of our forebears mirrors what Richard Dawkins discusses in his book; the idea that we as human beings are a product of chance.

As he writes: “Each successive change in the gradual evolutionary process was simple enough, relative to its predecessor, to have arisen by chance. But the whole sequence of cumulative steps constitutes anything but a chance process, when you consider the complexity of the final end-product relative to the original starting point.”

Every step our ancestors took in the process of our eventual being was also simple enough. They were more often than not steps taken quite by chance. But the ‘whole sequence of cumulative steps,’ as Richard Dawkins writes regarding Evolution ‘constitutes anything but a chance process’. I’m not – at present – trying to come up with any conclusions to this line of thinking save to say there is something there, a link between the process of Evolution and our individual arrival in the world: the subtle changes which allow flora and fauna to evolve and the subtle actions of ancestors which cause us to be born. That link exists in the individual’s (animal, plant… or ancestor) progression through life – a progression which is a constant (battle might be too strong a word) will to survive.

We journey through life with intentions of doing things, going places and so on, always considering our own safety (survival) even if that consideration resides somewhere within our subconscious minds, rising to the surface every now and then when danger become more manifest. And along the way chance plays a part, altering our movements, delaying our progression, speeding it up, slowing it down and so on. Traffic Jams, the weather, forgetting keys… the list of things which impact upon us is endless; chance encounters with people we’ve never met or know very well etc.. If in retropsect we could map or list everything that happened to every one of our ancestors, such a map would appear to us (not only very big!) to have been designed (indeed, anything seen in hindsight appears to be so). It would seem utterly impossible for chance to be such a draughtsman; to create a specific individual from such an enormous number of utterly unlikely events in the course of what we call history.

But that is what chance did. As I said, I’m not looking at this moment to come up with any great conclusions, save to say that thanks to Richard Dawkins I’m looking at my work in a slighty new light…

Dame Myra Hess

I have just been chatting with my 97 year old grandmother who was telling me how she remembered going to see pianist Dame Myra Hess play at Reading Town Hall some time during the war. The name rang a bell and I remembered watching a programme about lunchtime concerts at the National Gallery which took place during the war when all the paintings had been removed to the mines of Wales. I was sure the pianist was the same and indeed, looking her up on the web I discovered this was the case.

I’ve never heard my grandmother say anything about this before and although it’s just a short memory and nothing of great significance, it nonetheless gives me a way into the past which wasn’t there before.

Same People

Having bought a copy of a photograph (St. Giles Fair, 1913) from the Oxfordshire County archives, I found when looking at the individual faces someone I recognised. Not someone I know or knew of course, but a lady I’d seen in another photograph.

The photograph on the left was taken on Headington Hill in 1903, and that on the right at St. Giles Fair in 1913. Below is another person I found in two different photographs, this time from 1908.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- …

- 32

- Next Page »