New Work 2

New Work

Goethean Observation: World War I Trench Map

Less a Goethean observation and a more general observation with reference to the Goethean method (click here to read more about Goethean Observation).

Note: The aim of this observation is not to write a beautiful prose account of the map, but rather to look, observe and find a hook upon which to hang the next piece of research into this subject.

The map has been printed on a large sheet of paper creased vertically and horizontally with lines where the map has been folded and opened. The paper itself is a brownish-white, darker along the lines of the folds and around the edges in places. The corners on the left hand side are a little dog-eared.

The map on one side shows the area concerned – a part of France as the map tells me at the top. This side of the paper is smooth to the touch, but on the reverse I can feel a tooth. Folding over the first fold, I can see the tooth on the ‘reverse’ very clearly. The [fabric of the] paper is made up of very straight vertical lines, with wonkier lines running horizontally. There are four ‘squares’ (actually rectangles) to each folded column and eight folded columns (7 creases) in all. There are four folded rows (3 creases).

The ‘square’ at the top of the first vertical fold on the reverse side of the map tells me this is a ‘Trench Map’. Like the bottom square, the colour of the paper is much darker than the rest. The two squares in between are like the colour of the map on the reverse side – possibly even lighter. This shows how the map, when folded, has a front and a reverse side. Having turned over the map so that this first fold appears on the right I can see all 32 ‘squares’ that make up the map. The folds are particularly prominent, some darker than others. Some of the squares show no sign – or at least – very little sign of wear. There are some splits in some of the folds – caused of course by the repeated action of opening and closing the map.

Six ‘squares’ along the top two are covered with words – French words and their English translations. The words are the names of landscape features such as tree (arbre), gate/stile (barrière), oak tree (chêne) and pond (etang). The rest of the squares, including one on this top row are blank. All one can see is the pattern of the paper’s fabric.

Turning the map over, one is aware of the holes and the sound the paper makes. It reminds me of a soft version of the crackle of a fire.

The drawing of the landscape takes up much of this side of the paper with explanatory texts and a key beneath as well as to the right of the map.

Looking at the details of the map, one can see the various features of the landscape – the woods, roads, hills (through contour lines), rivers, ponds or lakes and of course various towns and villages. All these features, along with the names and the grid are printed in a ‘black’ ink which actually appears as a light ‘browny’ grey.

What one’s eye is drawn to straight away however are the patches of colour on the right hand side of the map; blue and red. The colours have been used to colour a multitude of lines which run from the top of the page to the bottom. The majority of these are red. There is one dashed blue line which snakes from top to bottom to the left of the furthest-most red line and to the left of that, the same colour has been used to mark out the landscape features showing rivers, lakes and what appears to be marshy land.

The red lines themselves have been drawn in a sort of ‘stepped’ way and cover a quarter of the map up to the right hand side. Looking closely at these lines, one is made aware of the other lines of the map – black curved lines, straight vertical and horizontal lines; straight vertical and horizontal dotted lines – these lines divide each square (delineated by the other straight lines) into four quarters.

In each of the large squares there are numbers, the greatest of which appears to be 36. Among some of these numbers, there are also letters – P, Q, R, V, W, X.

As I look at the map I begin to notice the mix of French and English words/names. The place names are clearly French; La Boiselle, Thiepval, Authuille, Contelmaison, Beaumont-Hamel. In amongst these however are names like Tara Hill, The Crucifix, Railway Copse, Brickworks, Pond Bridge and Cemetery. There also appear to be instructions: ‘35 to 40 ft deep: Impractical for Cavalry.’ There is also a largish hole above Pozières.

Folding the paper up, it fits entirely in my hand. It is like a concertina, about an inch thick without too much pressure applied.

Looking more closely at the front of the folded map, I can see the words:

Trench Map

France

Sheet 57D S.E.

Edition 2.D.

There is then a diagram – an ‘index to adjoining sheets’ beneath which are the words and numerals:

Scale: 1/20,000

On the left hand side of this ‘face’ are what appear to be two initials, DM. The map smells of its age, a musty smell of something that for a long time was forgotten.

On the diagram I can see a small square which has been shaded in to distinguish it from all the others. One can see that this piece of paper is part of a much larger map measuring ‘eight maps’ wide and ‘eight maps’ high.

The map is clearly old. The date 1916 has been printed on the ‘map’ side, but even without this, the style of the printing and the condition tells me it’s of some age. Through its age it has expanded in its folded form. The folds aren’t as crisp as they were. It has no doubt lain forgotten in an attic or some such place, acquiring its patina and its smell. As the dust has grown, the text has faded, although the edges of each letter are crisp. And still I can see the ‘DM’ in pencil on the left hand side.

It doesn’t resist being folded again. First vertically and then horizontally.

I unfold it and instinctively flatten it down. The folds in places rise up. The fold which runs vertically through the red lines does especially. This part of the map won’t remain flat unless I press it down with my hand. As I do, my head instinctively lifts a little and my eyes move along the lines of red to rest around the village of Thiepval.

These actions would no doubt have been repeated in the past when the map was perhaps more pristine – when the folds were sharper and the map lay flat.

The map, when I lift it up, seems to want to fold into a particular shape. It doesn’t want to be put away, but rather be folded so that two columns remain in view. The folds which delineate this part are a darker brown than all the others. In this section of the map is a concentration of red lines and blue lines.

The way it folds suggests that this was what was most important. When I pick up the map to fold it completely, it folds so that the ‘front’ and ‘reverse’ are tucked away. The front now is one of the segments or ‘squares’ containing French words (Sondage) and their English equivalents (Boring – as in cut).

The past movements associated with this map are therefore recorded in its folds. It resists being folded any other way.

We know the map was made in 1916 with minor corrections to details on 15.8.16. This is just six weeks after the first offensive in the Battle of the Somme. Shortly after this period the map would have been replaced with another as the landscape changed with each offensive.

When I look at this map from the comfort of my own front room I see history – albeit one written in a less conventional way. It still has words and pictures.

For much of its life it was no doubt a curiosity. Maybe it was a reminder for those that were there who when looking at the lines would have seen something very different – not on the map but in their minds.

Those who used the map would have seen something else. By August 1916, the colossal tragedy of the first day of the Somme would have been etched on everyone’s mind. The contour lines can hardly tell the reality of the ground’s undulations, and yet it was these which meant the difference between life and death. The map serves to distance us from reality.

Considering its past, the action of being folded and then unfolded over and over, one can almost imagine a bellows lifting and then depressing, letting out air like a breath – a last gasp.

The map is like a palimpsest, albeit one which is just a single print. One can see the original landscape which over the years changed as landscape features assumed English monikers. It is a place that appears at once to be real and imagined – a non sort of place.

‘The Poodles’, ‘The Dingle’, ‘Willow Patch’, ‘Round Wood’, ‘Birch Tree Wood’, – they all have the sound of something made up – a children’s story. ‘Middle Wood’, ‘Villa Wood’, ‘Lonely Copse’. There is even marked ‘a row of apple trees’. These names – these alien names – all appear on the right hand side of the map; on the left, large swathes of woodland go unnamed.

The same is true of road names.

Observation of certain parts of the map has changed the way it moves – these movements seem impressed into the map’s fabric.

When I stand to look at the map, I stand as, no doubt, others stood around it. I can again imagine the creases as sharper, the colour of the paper whiter, the lines more vivid.

Looking at the map, unfolding it and folding it, smoothing down the paper, one gets the sense of an individual. 1/20,000. The map as an object tells me about the individual who looked at it. What is pictured tells me – when I think of the scale – about the thousands of men killed on that first day of the Somme.

One gets the sense of other maps printed before this one, upon which this one is based – each one covering over the horror of the most recent losses of life. They become like shrouds.

Each one would have been used to plan the next map, and the next, and so on, until there weren’t any red lines left.

Past and Present Postcard

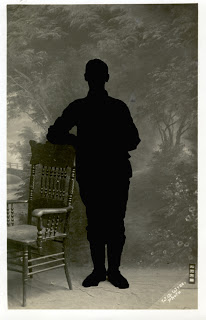

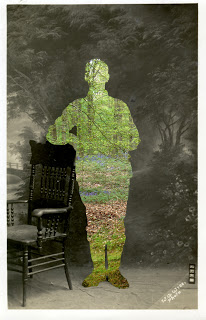

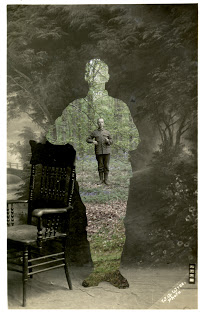

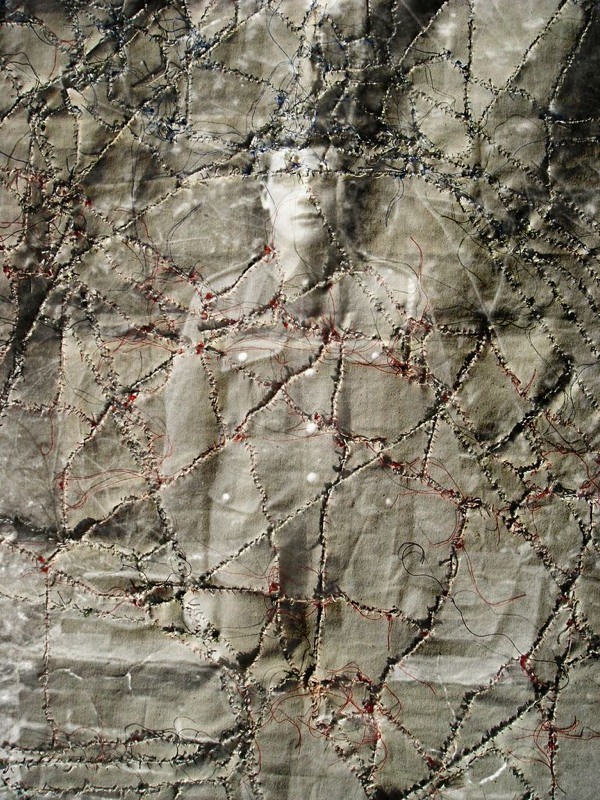

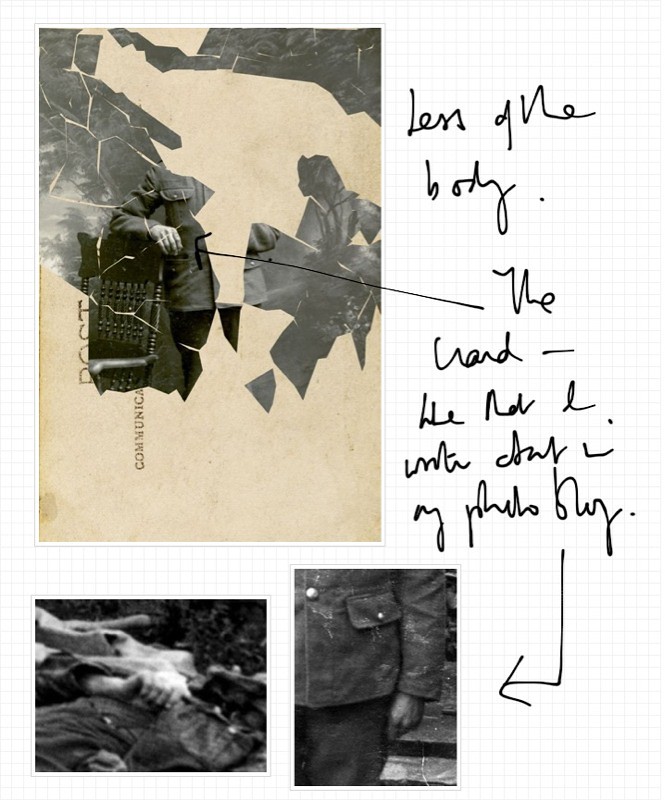

The image below is the last in a series I’ve made using both an original World War One postcard and a photograph I took in Verdun. All are works in progress.

I’ve been fascinated with the backdrops in some of these postcards for quite some time now and have been looking at ways of using them in works relating to the Great War and, in particular, the issue of empathy.

The original postcard is of course in black and white (with a greenish tint) and shows a soldier about to head to the Front, standing, leaning on a chair.

Behind him is an idealised image – an idyllic, invented landscape, a far cry from what he was, perhaps, about to encounter, but close in some respects to what we find on battlefields today; where there were trenches, arms, barbed wire and bodies, there are now trees. And amidst the trees, incongruous concrete Pill Boxes stand and watch as the seasons come and go. Everything is slowly reclaimed. The trees in the image at the top of the blog spill to reclaim the past – the interior of the studio – through the gap left by the missing soldier.

I have placed the solider back beyond the gap left by the vague shape of his own body, to remind us that people like the soldiers we see in all these postcards, were once like those of us who have visited the battlefields. They too would have known what it was to stand in a wood. To listen to the wind blowing through the branches.

To stand and do just that, is one way to remember them.

Work in Progress

A Flash of Genius at the London Art Fair

Yesterday, at the London Art Fair, I found – amongst a plethora of ‘not very good’ and downright terrible art, an artist whose work – although disturbing -truly impressed me. It’s not the sort of work you’d want on your wall perhaps, or which would likely be snapped up by the likes of those idiots who it seemed were happy to shell out 5 grand for a print of one of Damien Hirst’s assistant’s facile spot paintings (albeit one signed by the Overlord of artistic tat), but its power was striking.

For a number of years I’ve looked to create work which facilitates an empathetic engagement with anonymous individual victims of past atrocities. This work has variously found its form in paintings, sculpture and mixed media pieces using documentary and archival material such as photographs. Where these photographs have been black and white, I’ve looked to see how colour might be used to foster that empathetic reaction.

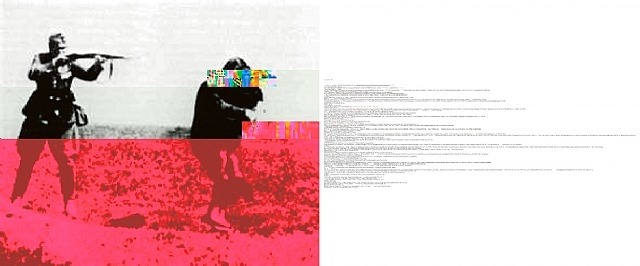

David Birkin’s work, ‘Untitled I’ does everything that I have tried to do. It’s a brilliantly conceived work and one which is conceptually perfect. The work, disturbing as it is can be seen below.

The image shows a woman about to be shot by a German soldier. The woman, like so many of the Nazi’s victims is anonymous, one more human being to make up the grim toll of 6 million killed in the Holocaust. But where so many names have been forgotten, many of course remain, trapped – like flies in amber – in the meticulous records kept by those who carried out these unimaginable crimes.

The black and white photograph printed on the left of the image has been distorted with fragments of colour, and on the right of the image we find the computer code for the original digital image, into which Birkin has placed the name of one of the countless victims. This ‘anomaly’ in the code is revealed when the image – with the anomalous name – is reprinted. The distortion is the name as read by the computer.

It is a brilliant concept. The computer code, without the name, is to (most) human eyes, little more that an incomprehensible mass of letters and numbers. It’s the equivalent of the vast and grim statistic offered to us by history. Its equivalent image is black and white – a far cry from the reality of a world full of colour – the world we know and which every one of the six million victims knew. And yet when a name – an individual – is inserted, the image is changed (distorted) with a pattern of colours, reminding us that the world of the Holocaust was not black and white, but one full of colour, of summer days and everything which we take for granted today.

The average man, woman and child are not the types of people who normally make up history, unless they are heaped together as victims, masses and mobs. They are often anomalous where history is concerned, but nonetheless vital and full of colour, something which Birkin’s work brilliantly portrays.

An Unfinished World

First thoughts on Graham Sutherland, ‘An Unfinished World.’ Modern Art Oxford

|

| Graham Sutherland, Dark Hill – Landscape with Hedges and Fields, 1940. Swindon Museum and Art Gallery © Estate of Graham Sutherland |

In his excellent book, ‘A History of Ancient Britain,’ historian Neil Oliver writes:

“All of Britain was a work in progress as nature set about reclaiming the land. The period of hundreds of thousands of years known to archaeologists as the Palaeolithic – Lower, Middle and Upper – was over. The remote world of the mammoth-hunters of Paviland, even the lives and times of the Creswell artists and the butchers of Cheddar Gorge belonged to the past. The ice of the Big Freeze had drawn a line that separates them from us, then from now.”

This line in our history, this schism carved through time in much the same way as valleys were carved and gouged by ice from rock, is a place I find myself observing when I look at some of Sutherland’s haunted landscapes. They are silent spaces, from which it seems humankind is quite estranged; banished even. In some, it’s as if Man has yet to appear, as if the world is part of a parallel universe, similar in some respects, but altogether different. There are, as well as those landscapes which seem divorced from knowable time (from history), landscapes from the recent past; ruined prospects of towns wracked by war. And while the source of this ruination is Man himself, the sense which Sutherland creates is one in which Man again ceases to exist. It’s almost as if through both types of landscape (those we might – very loosley- describe as rural on the one hand, urban/industrial on the other), Sutherland is reminding us that for the unimaginably greater part of its existence, the world did not know us; that for the equally ‘impossible’ span of time that stretches ahead, the world will have no need of us either.

This sense of oblivion haunts Sutherland’s landscapes; Earth’s indifference towards us – in the grand scheme of things – permeates almost every canvas and drawing, no matter how small. They each seem to echo the wonderful words of the 17th century writer Sir Thomas Browne, when he writes in ‘Urn Burial.’

“We whose generations are ordained in this setting part of time, are providentially taken off from such imaginations. And being necessitated to eye the remaining particle of futurity, are naturally constituted unto thoughts of the next world, and cannot excusably decline the consideration of that duration, which maketh Pyramids pillars of snow, and all that’s past a moment.”

On some of Sutherland’s drawings, the artist has drawn a grid of horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines. Grids like these would often be used when scaling drawings up to full-size works, and perhaps that is what the artist intended them for. When I see them however, I see them not as something detached from the work itself – a mere tool for reproduction – but rather an integral part of the work. It’s as if the artist is trying either to order the chaos which he’s rendered on the page (and which he’s no doubt observed in the real world), or do battle with Man’s certain oblivion and relative obscurity, imposing his mark on the landscape; his dominion over the world.

|

| A Farmhouse in Wales 1940. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales |

If the Farmhouse in Wales above is slowly dissolving back into the landscape, then perhaps it can be seen as a metaphor for man’s own ineveitable fate. The grid therefore, this means for scaling up, for seeing more clearly and in greater detail (the bigger picture as it were) is perhaps then a means for trying to understand that fate, for comprehending those ‘pillars of snow,’ so beautifully described by Browne in 1658.

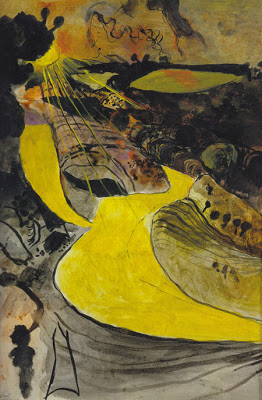

|

| Welsh Landscape with Yellow Lane 1939-40. Private Collection, London |

In a video to accompany the exhibition, curator (and artist) George Shaw, describes how the use of yellow gives the appearance of a landscape which is jaundiced; perhaps sick. I however see this sickness not as a part of the landscape, but a part of our own vision of ourselves; our place in the ‘grand scheme of things.’ Even where Sutherland has painted machines (which by their very existence would seem to point towards the existence – and therefore relevance – of mankind), there is still the sense of Man’s complete absence from the world. It’s as if, as I’ve said, these paintings depict those two great and awful spans of time, between which Man’s existence is pressed, like rocks beneath the vast sheets of ice, which once crawled and covered this place we call home. (Even those gargantuan glaciers – in places almost a mile thick – which smothered the country for so many thousands of years, would seem like Browne’s ‘pillars of snow’ when considered against the backdrop of eternity.)

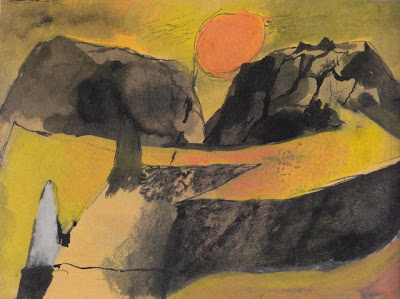

In the exhibition’s first few paintings, we find these same desolate landscapes, replete with standing stones (for example, in ‘Sun Setting Between Hills’ below) such as those found at ancient sites throughout the country.

|

| Sun Setting Between Hills 1937. Private Collection |

At once these landscapes become charged with mystery, and like those paintings which show, for example, cranes gorging themselves on the landscape, we are presented with evidence of Man’s existence. The standing stone and the ruined urban landscape, mirror one another. Poles apart, they seem to delineate this landscape in which we, for a short time, have strutted the stage of our existence. No-one is likely to walk the yellow roads which cut through the world above – yet someone must have been there.

|

| Interlocking Tree Form 1943. The Whitworth Gallery, University of Manchester |

Despite this apparent absence of Man, the trees in some of Sutherland’s landscapes seem almost human, at least in their gestures. Some such gestures echo the agonies of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, (for example, in ‘Interlocking Tree Form’ above) while ‘Study for a Blasted Tree,’ calls to mind Goya’s ‘Disasters of War.’

|

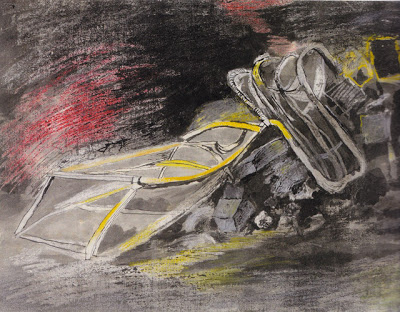

| Fallen Lift Shaft 1941. Junior Common Room Art Collection, New College. |

It was whilst looking at the painting above, that I found myself thinking of William Blake. In this work, ‘Fallen Lift Shaft,’ there is a small patch of red which is reminiscent of some of the poet’s own paintings. The lift is on the one hand a casualty of war, a victim of Man’s aggression. On the other it’s a symbol of his descent. It is perhaps the Fallen Angel.

The exhibition is titled ‘An Unfinished World‘ and whilst reading Richard Dawkins’ book ‘The Ancestor’s Tale,’ I found a quote, which for me encapulsates what that title means. The world, with or without Man, is always unfinished. Dawkins writes:

“The second connected temptation is the vanity of the present: of seeing the past as aimed at our own time, as though the characters in history’s play had nothing better to do with their lives than fore-shadow us.”

In other words, we are not the end, just as we weren’t the beginning. And it’s this conceit which Browne cautions against in his meditation on death discussed above. Sutherland’s landscapes are for me, the equivalent of trying to imagine one’s own non-existence in a world which is always, as Neil Oliver writes, ‘a work in progress,’ one in which nature will one day set about reclaiming from Man.

One might think it’s possible therefore to view Sutherland’s paintings as a warning against this conceit. But to do this is in itself a kind of conceit. The fact is, we are just another part of the landscape. The yellow road was there before us, and after us the yellow road rolls on. Sutherland’s paintings are not warnings, but statements of fact.

And while this might sound somewhat depressing, another quote from Dawkins (again from ‘The Ancestor’s Tale’) might just lift our spirits:

“As physicists have pointed out, it is no accident that we see stars in our sky, for stars are a necessary part of any universe capable of generating us. Again, this does not imply that stars exist in order to make us. It is just that without stars there would be no atoms heavier than lithium in the periodic table, and a chemistry of only three elements is too impoverished to support life. Seeing is the kind of activity that can go on only in the kind of universe where what you see is stars.”

|

| Landscape 1969. Harry Moore-Gwyn (Moore-Gwyn Fine Art) |

In many of Sutherland’s works, our very own star, the sun, is present such as in the work above. In one of the first paintings within the exhibition, to the last (painted just four years before his death- see below) the same sun is in view.

|

| Twisting Roads 1976. Private Collection. |

And we – like Sutherland – can only see it, we only know it, because we exist.

Perhaps therefore, in Sutherland’s work, humankind is in evidence after all.

Geophysics and Henry Taunt

Since working on the archaeological dig at Bartlemas Chapel, I’ve been looking for ways to create work based around my interpretations of the site. A starting point for my research is an image created through a Geophysical survey of the site.

It shows areas of high resistance (pale greys and whites) and areas of less resistance (dark greys and blacks), revealing patterns beneath the surface of the ground caused by the remnants of walls, buildings, ditches etc. Its indistinct aesthetic (vague shapes and outlines) is perhaps a metaphor for the way we perceive the past, which is itself, at best, always the most ill-defined and inexact picture.

Somewhere within this picture however were all the things we found, including the piece of mediaeval pottery below.

The contrast between the black and white of the resistance survey image and that of the red-orange glaze interests me as regards the allusion to what we know of the past as opposed to what actually happened.

This contrast also comes to mind when looking at photographs of Bartlemas Chapel taken by Henry Taunt in 1912.

It’s amazing to think that below the black and white surface of the photographs, beneath the ground, the same piece mediaeval of pottery is there, waiting to be discovered, along with the bones of those who were buried there centuries before. Zooming in, as if to get a closer look, the image begins to change, becoming indistinct like the resistance survey images.

New Work (WW1) 2

Looking again at the latest work I’ve done (see previous entry), I decided to make the image of the man less clear. Taking away his face, I found my attention drawn to his hand which in turn reminded me of some work I’d done on hands with regards photographs from World War I.

New Work (WW1)

Again using the idea of the lines/patterns of trenches, I’ve reworked an earlier idea using an old World War One postcard.

Goethean Observation: Mediaeval Shoes

I am looking at a shoe made of leather which is on display in a glass case in the Museum of Oxford. With it on display are a number of other leather artefacts, but I will reserve my observations for the shoe in question.

The shoe, which I believe is that for a right foot, is dark grey in colour. It rises above the ankle, it’s quite small but appears to be one that would have belonged to a man. It has a small round metal buckle which appears to be the only fastening. It’s a little worn at the edges, particularly at the front, but not so worn on the back; it’s more or less intact. The upper part of the shoe has been cut in six places. The cuts have been made on the right hand side and the last cut which is more of a hole has been cut into the top of the shoe. The buckle is also on the right hand side. It’s round with a metal part on the inside such as one would find on a belt buckle. Opposite this, on the left hand side is a small hole which I assume is the fastening. Looking at the buckle, and the small metal part inside, I assume that there was a strap which passed through the buckle and around the shoe.

Looking into one of the cuts made in the right hand side of the shoe I can see three small holes in the bottom at the edge. The shoe is about 8 to 9 inches in length, the back of the shoe rises approximately 4 or 5 inches. The shoe is behind glass so obviously I cannot touch it.

The sixth hole cut into the top of the shoe has a cut in each of its edges, as if the hole was made first by cutting two crossed lines into the leather and then making the hole from these. The first cut in the shoe, that nearest the sole, is about 2 inches in length, the second about an inch, the third and fourth slightly smaller, the fifth about half an inch long. The hole is about ¾ inch in diameter.

The shoe has been packed inside for display with a white material. Looking at the back right hand side of the shoe (just behind the ankle) I can see that it has been cut, but it seems to be part of the shoe’s design, to ease the task of putting it on. The shoe has also been cut down the centre, again part of the design, to about two inches from the buckle. The sixth cut – the hole – is about an inch and a half from the end of this cut.

The right hand side of the shoe is that which is most visible and I can clearly see the texture of the leather, I can almost see the shape of the heel where the shoe has moulded to the shape of the wearer’s foot. There is a large crease just above where the ankle would be (which seems to correspond with the idea that the shoe would have been fastened with a strap). There is another large crease running down from the buckle towards the sole.

Part 2

What is clearly seen in this shoe is the apparent simplicity of its construction. I can almost see it as a single piece of leather and as I consider this I begin to picture it in the hands of the tanner. I can almost see the carcass of the animal from which it was taken (I wonder for a moment about the cow; where had it grazed, when was it killed), the man who cut it and prepared the leather. I can hear the noise of the place in which he worked and see this piece of leather as the means by which he is able to live. I assume he knows the shoemaker? Did the shoemaker live in the town? Did the tanner? What things were on his mind as he worked the leather in the 13th or 14th century? And what about the buckles, where were they made? Who made them? Were they sent to the shoemaker along with other buckles? What was going through the mind of the man who made it? What was happening in the world when it was made? The same question applies to the tanning of the leather and the making of the shoe itself.

At some point the leather from the tanner and the buckles (from the ironmonger?) would have found their way to the shoemaker. Did he work alone? Were there others working with him? Were the shoes bespoke, made to fit individual buyers, or did he just make them in bulk? Did he know the man who wore this shoe? If he did, what did he talk with him about as he measured up his feet? What was happening in the city at the time, how long had it been since the tanner had sent the leather? What was the process of making the shoe, how long did it take? What was the buyer wearing on his feet as he talked with the shoemaker? Did the buyer select the leather or was it just whatever was available? Why did the buyer chose this particular design? What were the shoes for – everyday use? What was the shoemaker’s workshop like? What were the sounds both inside and outside?

Having talked with the buyer, the shoe maker would begin to mark the leather. What did he use? A piece of chalk? He would cut the leather to shape, making the cuts that I could see in the shoe – those that were intentionally part of the design. And then, having cut the pieces, he would begin to sew the shoe together. Did he do it in the light or in the dark, under the light of a candle? What did he think about as he worked the needle and thread? Was he an old man. Did the drawing of the thread help him in his thoughts? What were the sounds as he worked? Quiet, except for the noise coming from the street. As I see him work, I begin to feel the rhythm of his body, I feel his aches and pains. I feel the squint of his eyes as he tries to see more clearly what he is doing.

Did he like the man for whom he made the shoes? When he finished the shoe, did he pick it up and look at it admiringly, squinting again to make sure everything was perfect? It had to be, this after all was how he made his living.

The final touch, the attaching of the buckle. The shoes were ready to be collected. The buyer comes and picks up his shoes. He enters the workshop (perhaps the shoemaker delivered them to his house?). What time of year is it? Winter? Is it cold outside beyond the warmth of the workshop? One can hear the sounds of the outside pour in through the door along with the chill. Or maybe it’s summer? Is the workshop warm, stifling? The man is eager to try on the new shoes. He takes off his old ones and takes the new pair from the shoemaker (what do they feel like, what colour are they?) Do they carry on their conversation from last time, or do they just make small talk? The man tries them on, they fit perfectly. He walks in them for the first time, up and down the workshop. The shoemaker smiles and waits for the money. How much did they cost?

The man takes the shoes. Does he wear them out, does he discard the old shoes he’s been making do with for so long? Where does he go when he leaves? What does he do, what is he thinking about? Does he speak to anyone? What does he see as he walks in them for the first time along the streets he knows so well? Over time the shoes – the leather – begin to soften and fit themselves to the shape of his feet. His walking makes the creases and folds in the leather. They fit better and better but there is a problem with his right foot. He has bunions which are making walking painful and difficult. But there’s little he can do about it except walk as best he can, his grimacing face showing the signs of his discomfort. Do people ask if he’s okay as he limps down the street, or is it a common sight in mediaeval times?

Where does he wear the shoes? Which streets did he walk down whilst wearing them? Inside which buildings?

The pain gets worse and in the end it’s all he can do, in a moment of desperation to take a knife and cut two lines in the shape of a cross in the top of his shoe directly above the bunion. Did he start by making the one cut and proceeding to cut more as the condition of his feet deteriorated, adding the cuts on the side? Or were they all cut at the same time? What went through his mind as made the cuts? How old were the shoes when he had to cut them? Was it just the one shoe that was cut this way?

As time goes by, the shoe is discarded (what about the other?). Perhaps the man’s condition became so bad the shoe no longer fit him. Perhaps he died? Where was it thrown away? Somewhere wet, somewhere that kept them so well preserved. The moat of the castle? The river? Who threw them in? The man himself – or perhaps his wife? Maybe someone else. Did they think of the man when they threw them away? What happened to the shoe after it was discarded. Did it float on the surface of the water? Was it dark when they were discarded? Was it light? What could be seen, what could be heard the moment the shoes hit the water’s surface?

Part 3

The ground.

The air.

Pressure. Weight. Weightlessness.

Something lives within, then is gone.

The space left behind; the imprint of weight and weightlessness combined.

The wet. The mud.

Soft. Hard

Heat. Dust. Scratching. Expanding.

Held together, seams, thread, pressure.

Stained by the long dark. Sudden break. Noise and light.

Empty. Fixed in shape by the memory of something living.

Long gone to the ground.

Part 4

I am made of many parts, there are different aspects of my being, the leather, the threads, the holes, the emptiness inside. The absence of the body (the foot) around which I was pulled tight, which moulded my shape. I moved, I expanded as I felt the pressure above and below me. I was squeezed between the two or sometimes left in the limbo of lightness. I breathed. I took in water, I dried out. I absorbed smells and over time my smell changed from that of the shop in which I was made to the smell of the house in which I was sometimes left. I was the smell of the man who wore me and the smell of the streets of which I was a part; the streets left behind with versions of myself; depressions left in the ground. I felt pressure outside and within but now I feel nothing, just a limbo of lightness. I smell of nothing. The pressure of the mud which encased me, the darkness, the shape in which I was fixed for centuries. I was beneath the ground the shape only of myself, of one of those depressions left in the street. Long, long dark. Silence. Then light, sudden light and noise and careful hands. Not like the hands of the man who owned me, but the hands of the man who made me, the careful hands of the shoemaker who cut me into shape, who carefully punctured the holes for the thread, who looked at me with great satisfaction. Now that same look is extended to me once again and I am light, and in the light. I have come an impossible distance, but am in the place where I have always been. Where is the other shoe? Where are all the other shoes made by the shoemaker, made by all the shoemakers?

Gesture

One of the ways I use this Goethean method of observing is by using it has a framework on which to hang a series of questions (Phase 2). I find this a good way of trying to understand what the shoe might have experienced over the course of its ‘lifetime’ by trying to locate its changing place within a mutable, physical world. It’s also worth, once I have finished writing, going back over what one has written so as to try and tease out the ‘essential’ elements of what has been observed; these elements can then be used to try and locate the ‘gesture’ of the thing.

What I notice when reading over the text is how the shoe is often positioned at various thresholds. A number of words seem to suggest this:

Ground

Air

Weight

Weightlessness

Thread

Pressure

Filled

Empty

(Hollow)

Memory

(Forgetting)

There is also the fact that the shoe exists at the threshold between the animate and the inanimate, between man and object. “As I see him work, I begin to feel the rhythm of his body, I feel his aches and pains. I feel the squint of his eyes as he tries to see more clearly what he is doing.” Of course it maybe that he felt no pain and didn’t squint, but nevertheless, what one can find distilled in the fabric of the shoe is the rhythm of the maker’s own body, as well as of course, that of the man who prepared the leather, the buckle and last but not least the wearer.

There is also a threshold which is a little more difficult to explain; that between conscious thought and unconscious doing. For example, one can imagine the shoemaker making the shoe almost unconsciously, as if he has done it so many times before, the action is almost a part of his being like walking. But coupled with that is what he was thinking whilst unconsciously ‘doing’. Nothing works in isolation and I like to think that whatever he was thinking somehow – no matter how perceptibly or imperceptibly – translated itself in whatever way, into his actions – in this case making the shoe.

The shoe therefore exists at these thresholds too; between the inanimate and animate, conscious thought and unconscious doing, and, it could be said conscious doing and unconscious thought.

Thinking further about these thresholds, I began to see the shoe as a kind of spring, one which over a period of time is more and come compressed from both the weight of the wearer and the pressure of the ground on which he walks. Looking at the shoe today, one can almost imagine it, as a spring, unwinding like a clock, telling a time that to us at least barely changes at all.

Turning then to the shoes in Majdanek, one can imagine them all this way, as springs which are slowly unwinding. In this sense, the mountain of shoes is imperceptibly moving, exerting by degrees an influence upon its surroundings.

Just as a body lying buried in the ground continues to exert an influence upon its surroundings, so does every shoe, and I can’t help but imagine, that this uncoiling inside each one is the slow release of a long unbroken memory, of the human who wore them and the pathways which they walked.

Goethean Observation: Mediaeval Pottery Shard

Part 1

This piece of pottery can fit in the palm of my hand. The shard measures just over three inches in length. The narrower side of the shard (the bottom) is around two and a half inches in width and the top (the rim) about three inches. It is delicate, quite thin – about four millimetres thick. It weighs very little and is rough to the touch. As I rub my thumb and forefinger over its surface I can feel the indentations, ridges on its surface. Looking at it, the surface on the outside appears smooth. Of course here I will have to distinguish between the outside and the inside of the shard. Looking at the shard sideways on, I can see how the shard bows to one side. This curve appears quite uneven but from the top of the shard, it appears quite uniform. Looking from the top I can see two ridges running down the surface (the outside) of the shard just below the rim. These ridges are either side of a groove and find their opposites on the inside. Where there are ridges on the outside so there are grooves on the inside and vice-versa. As I feel the surface of the pottery fragment, bits fall onto the page like small grains of sand. I can detect more ridges, though more shallow than those which run across just below the rim on the outside. Furthermore these ridges are on the inside of the shard. Closing my eyes I can feel about eight or nine.

The shard becomes thicker near the bottom – almost twice as thick as at the top. In the side of the shard I can see small holes – about a dozen – little more than pinpricks. The material is light grey in colour and moving my finger down the edge I can detect a shallow groove running from the bottom of the shard to approximately halfway up. The colour of the shard as a whole at first glance is very dark grey, almost like charcoal, perhaps a little lighter. On the outside there are patches where the shard is darker and indeed lighter than other parts. There are also very small patches of colour in the shard, tiny patches which are sandy in colour and even smaller patches which appear white. Although mainly grey, there is a hint of brown throughout the fragment, particularly on the inside of the shard where there is a greater build up of material particularly around the ridge near the top. The colour and patination on the inside of the shard is much less uniform than on the outside. Just as I can see more ridges and grooves in the surface, so I can see more variations in colour. In the centre there is a large patch of light grey within which I can see speckles of white and brown. I can see lines running through the middle of the patch. Towards the top of the shard on the inside right as I look at it, I can see distinct brown markings and around this are what look like crumbs of dirt – dark grey which if gently rubbed fall from the shard. There is some writing on the inside too, just beneath the top of the rim written in black – OX TMS 02 II with a 35 in a circle beneath.

On my fingers I can see patches of grey from the surface of the shard. I can see the dust on the piece of white kitchen towel on which the shard is resting on the table. I can see particles on the surface of the table too and my finger tips can feel the edges of the shard even though I am no longer touching it. If I hold the shard in my hands and without looking move it around I can feel both its smoothness and its edges which though not sharp are nonetheless rough. This object, without looking, becomes an object in its own right rather than a part of something else, but the rough edges tell you there was once more to this piece. Feeling the smooth side with its ridges and grooves one can feel suddenly the sharper rougher edge, which is quite at odds with the rest.

Looking at the shard from the inside, it’s difficult to see this object as being anything other than a piece of something. Looking at it I can see of course see (even if I hadn’t known already) that this piece of pottery is a broken piece of something bigger. However what that bigger something might have been is difficult to discern. It’s only by observing the piece from certain angles that the bigger picture’s revealed. The curve of the shard, looking at it from the top down, shows the bulge on the right hand side. One can also see a tapering of the two longer sides towards what is the bottom of the piece and even though these sides are jagged and obviously broken, they carry nonetheless the dynamics of the shard. One assumes that whatever pot this piece was a part of it narrowed towards the base. Looking at the curve again from the top and holding the shard in my right hand, I can see roughly how the curve would become a circle using my left hand as a guide. In order however to judge its height, I need to know the size of the base. If I hold the shard in my left hand and look at the shard from the bottom I can see the curve and with my right hand get a sense of its diameter. I then look at the sides of the shard and draw the lines down towards the base, thereby gaining a sense of the volume of the pot from which this fragment remains.

[drawing the line up and down mirrors the physical gesture of the potter’s hands]However I must leave the reconstruction to one side for a moment because to understand this shard fully I need to take it back in time. I need to see it first as part of the collection in the museum stores, stowed away in a box with hundreds and thousands of other pieces. I need to see it being assessed and given its reference number (visible beneath its rim). I need to take it back to the day it was pulled from out the ground in 1985 in the area of the Trill Mill Stream in St. Aldates where it had lain in the dark for perhaps as long as 500 years. Half a millennium in which time its original colour was changed by it being in the waterlogged ground. Was it broken in the ground, or thrown away because it was broken already? Either way this fragment has been an object in its own right for several hundred years.

[the rings are testament to this other complete object]How it ended up in the ground I cannot say, but I can speculate that it was broken before it went in. There is evidence of burning on the surface of the shard (although one must be careful as the discolouration could be confused with burning). Perhaps this points to its main use – as a utilitarian piece of pottery used for heating food or drink? Whatever the answer, I can perhaps surmise that the fragment has had contact with fire. Perhaps that’s why it broke?

Certainly it was broken and it broke at a specific moment in time. The edges of the shard therefore reflect and illustrate this very specific moment in time. There is a sound associated with those edges; a sound I can feel when running a finger over the surface.

There is then within this single shard, evidence of two distinct time spans: 1) the staining caused by it being buried in the ground for several hundred years and 2) the moment it broke – a second in time several hundred years ago. There is also therefore a sonic quality to the shard in relation to these two periods of time 1) the long sound of silence and 2) the short sound of a break (one can also imagine that this breakage came with other sounds – perhaps that of the person responsible for breaking it?).

[what other sounds were there at this moment in the city?]Before the breakage, this fragment was part of a bigger object which we can speculate was used over a given period of time – how long exactly we can’t be sure, but we can imagine it being used in a mediaeval house – perhaps as part of its everyday activity. But what did it hold? What was it used for? Whatever the answer to these questions we can say that it held something and was used by people in the mediaeval period.

I have described the ridges and the grooves on the inside of the shard which tell us that this piece of pottery was made on a wheel. It was thrown. The rings are evidence not only of the movement of the wheel but of the person who made the pot. The wheel would have been turned by hand by the potter and then using his hands he could have drawn the clay up to make the pot. Every groove shows the movement and the physical presence of the potter.

[I’m reminded of a record player, with the needle drawn over the surface of the record, replaying a sound that has already happened. In a sense this shard reveals to us something that has already happened – not through the fact of the pot (as a whole) but rather the physical gestures of the potter. Drawing my fingers over the ridges and the grooves and keeping my eyes closed, listening to the everyday things going on around me, I can begin to find a window into the mediaeval world – not by sight, but by tough].Having described the two sounds associated with this fragment (silence and the break) as well as the two time-spans (the moment in time that it broke and the few hundred years it was buried beneath the ground) I can also add to that this sense of movement; the wheel being turned, the wheel turning, the clay being pulled up into shape and the physical presence and skill of the potter. Through touching the object we can make a physical connection with an anonymous individual who lived between the 13th and 15th centuries. We can make a physical connection with a time. Just what was happening when those rings were made? It’s almost as if what was happening at the time has been recorded in these grooves – including the thoughts of the potter himself.

With this piece of pottery therefore we can go back even further, for the shard is evidence of the pot and the pot is evidence of the skill of the potter – skill which was no doubt learned over a long period of time, passed down from other potters. It is evidence of an exchange between people in the mediaeval period. It is evidence of dialogue.

In terms of the fragment’s materiality we can also think about what it is made from. I think of the piece of clay sitting on the potters wheel, without shape, inert. Only through the intervention of the potter, through his eyes and his hands and through the skills he has learned over time could this piece of clay have become shaped into the pot of which this shard was a part. The question arises; what about the other parts of the pot? What happened to them? Perhaps they are hidden away somewhere in other boxes in the museum stores, or still buried somewhere in the ground. Perhaps like so much of the world from which this fragment originates they have been lost altogether?

It’s strange to think that when this fragment was part of a much bigger pot and indeed when it was in the ground, it was more a part of the world than I was ever likely to be. Now as I look at the fragment, I could say that the fragment is now more a part of the world than the person who made it, although of course it might be that there are people alive today who wouldn’t be here had it not been for this anonymous potter.

Any work made and inspired by this shard should not necessarily be considered as separate from the pot itself but rather as a continuation of the pot, and just as the fragment is a direct consequence of the thought, skill and physical gestures of a potter living some 5, 6 or 700 years ago, so this work might be considered the same. This shard has been living the same moment ever since it was made and so it continues in this work. The mind of the potter, my mind and that of all who see the work I make will somehow be connected.

I want to draw out from what I’ve written about the shard, points which I think will lead to further research as regards the production of works about the shard. The following is a list of those key points.

–

This piece of pottery can fit in the palm of my hand.

–

As I rub my thumb and forefinger over its surface I can feel the indentations, ridges on its surface.

–

This object, without looking, becomes an object in its own right rather than a part of something else, but the rough edges tell you there was once more to this piece.

–

Looking at the curve again from the top and holding the shard in my right hand, I can see roughly how the curve would become a circle using my left hand as a guide. In order however to judge its height, I need to know the size of the base. If I hold the shard in my left hand and look at the shard from the bottom I can see the curve and with my right hand get a sense of its diameter. I then look at the sides of the shard and draw the lines down towards the base, thereby gaining a sense of the volume of the pot from which this fragment remains.

[drawing the line up and down mirrors the physical gesture of the potter’s hands]–

Either way this fragment has been an object in its own right for several hundred years.

[the rings are testament to this other complete object]–

Certainly it was broken and it broke at a specific moment in time. The edges of the shard therefore reflect and illustrate this very specific moment in time. There is a sound associated with those edges; a sound I can feel when running a finger over the surface.

–

There is then within this single shard, evidence of two distinct time spans: 1) the staining caused by it being buried in the ground for several hundred years and 2) the moment it broke – a second in time several hundred years ago. There is also therefore a sonic quality to the shard in relation to these two periods of time 1) the long sound of silence and 2) the short sound of a break (one can also imagine that this breakage came with other sounds – perhaps that of the person responsible for breaking it?).

[what other sounds were there at this moment in the city?]–

The rings are evidence not only of the movement of the wheel but of the person who made the pot. The wheel would have been turned by hand by the potter and then using his hands he could have drawn the clay up to make the pot. Every groove shows the movement and the physical presence of the potter.

[I’m reminded of a record player, with the needle drawn over the surface of the record, replaying a sound that has already happened. In a sense this shard reveals to us something that has already happened – not through the fact of the pot (as a whole) but rather the physical gestures of the potter. Drawing my fingers over the ridges and the grooves and keeping my eyes closed, listening to the everyday things going on around me, I can begin to find a window into the mediaeval world – not by sight, but by tough].–

Through touching the object we can make a physical connection with an anonymous individual who lived between the 13th and 15th centuries. We can make a physical connection with a time. Just what was happening when those rings were made? It’s almost as if what was happening at the time has been recorded in these grooves – including the thoughts of the potter himself.

–

It is evidence of an exchange between people in the mediaeval period. It is evidence of dialogue.

–

Only through the intervention of the potter, through his eyes and his hands and through the skills he has learned over time could this piece of clay have become shaped into the pot of which this shard was a part.

–

Any work made and inspired by this shard should not necessarily be considered as separate from the pot itself but rather as a continuation of the pot, and just as the fragment is a direct consequence of the thought, skill and physical gestures of a potter living some 5, 6 or 700 years ago, so this work might be considered the same. This shard has been living the same moment ever since it was made and so it continues in this work. The mind of the potter, my mind and that of all who see the work I make will somehow be connected.

Goethean Observation: Old London Road

Part 1

Puddles, water, reflections.

Old road surface, scattered cobbles and stones.

Tyre tracks, undulating surface.

Birdsong, the sound of distant cars.

Shadows.

Hedgerows on either side, mainly brambles.

Old trees, young trees lining the way.

Fallen trees laying by the wayside – the rings on the exposed, cut branches.

The sky, the clouds, the position of the sun.

My shadow stretched across the road’s surface.

The squelching of people’s footsteps.

The rippling of the surface of a puddle in a pothole.

The almost indistinct wind.

Last year’s leaves scattered at the edges of the road.

A blackbird flies low over the ground.

Conversations grow as a couple approach.

Fly-tipping off the road behind one of the hedges.

Old clothes, pots of used paint, broken glass, bottles, cushions, an old teddy bear lying face down on the ground, pipes and bits of wood.

More cuddly toys face down, pale and faded. Saturated and soggy.

Huge tracks gouged out of the surface. Within them the water gathers. Reflections move with the wind blowing down the road.

The rounded stones of the surface. Smooth yet irregularly placed. A plane flies above cutting through the sky.

Molehills. A ditch running beside the road on its left hand side (as I walk west).

Large stones separate the ditch from the edges of the road.

The ground on the left hand side is at a different level to the road itself which I can see is raised up.

A siren in the distance over towards the city.

The sound of the stones – silent today.

At this point I began to move into the second and later phases. I had thought for the purposes of clarity to keep things in strict stage order (i.e. 1, 2, 3 and 4) but I think it’s important to record my results as they came. I shall write them as they were written (in italics).

There is a point walking away from the city where the road turns a corner and heads off to the left. Here the shadows are gathered together. The road also narrows or rather the countryside around it encroaches. The shadows and the trees. Towards the city the countryside backs away.

The passage of time in the tracks left by the wheels.

I started again to look at the road itself, as it was ‘presented to me’. I measured its width and found that it was approximately four paces wide and then started looking more closely at the stones which made up the road’s surface. There were I noticed some stones which were larger and flatter than the others. I also noticed that the road itself seemed to be on a slight angle, with the right side slightly higher than the left. I noticed, as I observed the surface, the sun catching the puddles and the moist mud around them. Yellow, ochre puddles.

Lichen on the boulders on the left hand side of the road, like fat unmade gravestones.

It was as I walked back up the road towards the city that I began to sense something about the road that wasn’t to do with its material or physical quality (although it’s precisely its physical and material quality which causes this sensation).

Walking back towards the city there is the sense of going somewhere for the first time even though I’ve walked this path many times before.

Silver, green lichen.

Blue stone.

The grass at the edges of the road [is] in patches encroaching on the roads itself.

In one section smaller stones have been used.

Many of the stones are either missing or covered with mud on which the grass then grows.

There was here a sense of the passing of time, the way of nature, as the mud and then the grass reclaimed the road. In the mud I saw the prints of horseshoes which made me think of its early years when horses and carriages, as well a pedestrians, would have used it. I thought back to the tracks left by wheels and found myself considering the road in terms of the changes in transport over the past few centuries.

Further towards the city, the stones disappeared all the more. They were covered in greater thicknesses of mud and consequently more grass.

As I have written, what is important to me in this kind of observation is noting everything that is going on around me, so as to give a more holistic view of the road, to not see the road as something which is separate from the landscape but a part of it (just as I was at that point not separate from the road but also a part of it). I became aware, through a gap in the hedgerow, of the blueness of the distance which I could see over the fields rolled out below.

Movements in the hedgerows (right).

The stones reappear like a spine running up the centre of the road.

It was on turning round and walking back up the road away from the city that I noticed very strongly a difference in the feel of the road. Almost straight away, I got the impression of leaving, of heading towards something familiar (even though for me the feeling should be reversed).

Walking away one can see the blue distant hills. To the left just the trees, parked cars and the radio mast.

A house through a gap in the hedgerow. Dark windows.

Walking away [East, away from Oxford] is almost like being in the past and walking towards the future, whereas vice-versa [West, towards Oxford] it’s like being in the present and walking into the past.

I appreciate that this may sound a strange thing to write, but with this sort of observation it’s very important to make a note of everything you see and indeed feel. This is all part of intuition, ‘seeing into’ the phenomenon being observed. As I said, I rather mix the stages together and in a sense some of the things I am recording here belong to the fourth stage (being one with the object [Intuition]).

The future is missing when walking towards the city. Curiously walking away from the city, one has the impression of leaving something behind, which I am doing by leaving behind something which is familiar.

The sense of leaving and going to a place which was evidently so much a part of this road is not something one finds so much on roads today. Roads today carry people through and around places, they are somewhat unattached to anywhere, whereas this stretch of old road is very much linked to places. It is very much a road which takes you away from somewhere and to somewhere else.

The undulating surface of the road… the divots and bumps… the stones, make it a slow road. It moves at the speed of thought and as such everything around it, the hills in the distance become a part. Again the difference between roads today (which one can hear constantly) and roads then, becomes very apparent. Because the hills, trees and surrounding countryside move at the same speed as you, you feel more attached to the world.

It’s a road which generates thoughts and carries thoughts because it is slow.

Movement of the road. Even though it feels like a road which definitely connects two places or rather things, it seems to have a sense of going on and on and never really ending. It’s as if walking on this road you will never get there. It connects you to two places you can never reach; the past before you were born and the future in which you won’t exist. The road is always the present, but a present made of all the past (moments upon moments) which can be found as you walk it.

Through this first set of observations I began to understand the road not just as a thing in its own right, but as something which is very much a part of the landscape. I found that in participating in the road, rather than simply just observing it, I began to participate in the road’s wider landscape, both physical and temporal. It’s a road in time as well as in space.

Part 2

The second stage of my observation of this road is to ‘take the road’ into my imagination and to perceive the time-life of the phenomenon; Exact Sensorial Fantasy as Goethe called it. To do this, I closed my eyes and recorded myself talking whilst drawing my thoughts, describing all the while what I could see in my mind’s eye.

Below is a transcript of my recordings (NB. The digital recorder malfunctioned and so the following is taken from three recordings). I have also scanned some of the drawings made whilst describing that below.

Walking along that road, looking at everything around it, the distant horizon, the trees, one feels a connection not only with the landscape but with everyone who’s walked or ridden along that path.

Along this road people are still carried. The thoughts they had as they walked or rode along arranged upon the ground in the stones just as the magnets arrange the tiny particles on tape. And even when the grass has completely covered it over, when people don’t walk hear anymore, when the voices are covered over as their bodies are and have been for hundreds of years there will still be the marks in the ground. The road is then a kind of palimpsest. When we walk we are writing ourselves on the ground, changing the ground just a little, imperceptibly, but a little, adding to all those changes which have been made before. Voices which are made more distant but which are never fully erased. Like a never ending book that has no start the lines just go on and on. Words are written over the top of each other, it’s not even a book, just a single line When the grass is grown over the road which it’s sure to do when the trees are bigger and they themselves have walked to cover the ground so that the road is just part of the forest, like a trench. What else will be gone? Will all the sounds in the distance be covered or will they be replaced by other sounds, things we can’t imagine now, just as those who walked the road a hundred, two hundred years ago could not imagine the sounds of an aeroplane or the distant drones of the traffic thundering down the bypass. Will the ground too have begun to cover those roads, to cover the buildings? I look at the grass, there’s not much road to cover, it wouldn’t take much to swallow it completely and yet one gets the sense that when that road has gone everything will have gone with it.

Standing back on the old road from Oxford to London running over the top of Shotover, this long muddy track which cuts through the grass into the distance. On one side is the hedgerow on other side the forest, much smaller than it used to be. Beyond the hedgerow are the fields and the distance. Looking at the road one can see the stones, all different types smoothed over with age, covered with mud and in the patches in between grass can be seen to grow as if slowly it’s trying to reclaim this road. In amongst the stones are also puddles in which you can see the sky the trees and if you look yourself, you can see yourself and inevitably the weather will change the days will become warmer, drier the puddles will dry up and take their images with them down into the ground up into the air. One imagines this place before this road was ever built. It makes one wonder what it takes for a road to be built long before the stones are put there when people first started walking that way when the first few footsteps marked a rough track which people followed through the landscape. Footstep after footstep. In many ways the landscape determines the route we take and therefore it’s almost as if the landscape is using us to draw upon itself. But what is it that makes this road a road? It’s not simply a collection of footsteps going in the same direction or back the other way. Every footstep is made, at first at least, consciously in this place. There is a conscious act behind the steps planted in the ground. Someone a long time ago hundreds of years ago had reason to walk there to get from somewhere to somewhere else, were they leaving or going, or coming? The road itself therefore becomes a kind of palimpsest which footstep after footstep is written upon the ground like words across a page and though footsteps which come afterwards gradually remove all traces of the others they can never fully remove the traces. Every footstep we plant changes the landscape just a little but a little nonetheless. Many of the trees are not as old as this road and yet this road is much younger than everything around it. What were those first footsteps thinking as they were planted in the soil. What languages did they speak. What images did they hold in their minds? What did the world look like around them? The forest was much bigger the sounds in the distance would not have been there. It would be the sounds of the wood and the forest, the birds and the human body which planted the footsteps in the first place. When I first went to the road I had the impression that although it led from somewhere and went somewhere else that nonetheless one could never reach the end but that somehow it would always keep turning; moving as if it was a conveyor belt of some kind.

Thinking about it now one can take that analogy and think of it instead as piece of tape which runs and runs and runs and which every step upon it is like the recording head changing the ground, changing the particles on the tape just a little. And just as we record when we walk so we also play, play the ground which passes beneath our feet. We can hear very distantly the thoughts which came before us. I could hear the sound of people’s footsteps planted in the mud, the same sound that’s been made on there for hundreds of years. And looking ahead one can imagine the grass that is already beginning to reclaim the road growing over the road entirely covering it again so that it’s hardly visible but should it do that, what would it mean? What else would have had to have gone for that to happen for no-one to walk there again? What else would have to be covered by the ground? What other roads, buildings, the town even. Perhaps then the woods would return to what they were? And though there’s not much left for the grass to cover it wouldn’t it seem take much for the grass to cover the road completely and yet one imagines what that would signify if it ever occurred. One would look at the radio receiver behind, the aerials, dishes and know that they would all be dumb and deaf. The mounting stones, one at the top and one at the bottom of the hill would be like gravestones.

What did the world look like for people to walk in this direction in this space? What drove people to walk here? What was on their minds as they did so? Were they excited, nervous, lovesick, jealous, happy? When the road was young and not a road but a small track one has the sense that people walked there consciously, that they were making the path through the landscape although the landscape was itself using them to write upon the world and that all those who came after were not so conscious of this path. This was simply the way you went.

There is the sense that when you walk along this road, you are adding to the thousands of fragments of thoughts left on the road. One can imagine these fragments as like the tesserae of a mosaic uncovered beneath the ground; one to which pieces are added just as they are taken away. What do the gaps tell us? Good litter, left on the road, not like that dumped in amongst the hedgerows.

Part 3

There is a sense as I walk and see the distant hills and the horizon that the road is waking as I walk. When no-one walks upon it, it sleeps. It uses our eyes to see the world around it. What lays beyond the hills? There’s a connection between our feet and our eyes. What lays beyond the horizon is hidden from everyone who walks this road, no matter what the century. The road is the people who walk it or ride it. The road is not so much a physical thing but a short trail of thoughts. The road is whatever people who travel it were/are thinking.

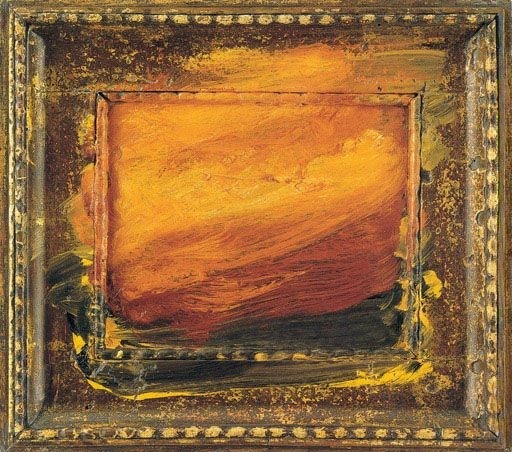

Old Sky

In response to my last blog entry, I remembered a painting by Howard Hodgkin which seemed to echo what I had written. It’s called ‘Old Sky’ and it’s a painting which, for me, is about the idea of that continuous cycle of time; of many cycles (single days) embedded in the cycle of years (which in terms of the pottery shard becomes a cycle of centuries).

The painting is an image of the end of a day and the remembered image of hundreds of days lost to memory and beyond. It’s about the act of remembering and the way the paint is applied to the frame becomes an attempt to reach beyond the limits of memory, to live again in the world when the memory was first formed. It’s almost frantic; an attempt not to forget what will certainly be forgotten. The frame remains intact, an acknowledgement perhaps that to relive a time that’s passed is impossible; that all that remains, inevitably, is a fragment of what has been.

As I alluded to in my blog, the relationship between colour and movement interests me a great deal and with this painting we have both colour and movement; movement when the painting was made and the movement of the act of remembering itself. For me, this reflects the idea of the cycle of a day and its relationship to the cycle of centuries; the relationship between the leaf and the pottery shard found during the dig. When I look at the pottery shard (below) I try to picture the world from which it has come. It’s as if the edges of the shard are like the edges of the painting, and while we can’t return to the world from which the shard has come, we can with the aid of the present attempt to imagine it.

I wrote in my last blog entry how when I dug the shard out of the ground, the colours at once melted back into the world from which they’d been estranged. This idea serves to illustrate that of moving beyond the frame or the edges of the shard in an attempt to re-imagine the past; how the act of remembering is as much to do with the body as the imagination – how it’s a fusion of the two; a product of an embodied imagination; one which moves in the world just like those with whom we seek to empathise.

Leaf and Shard

Out of a small pile of earth, greyish-brown in colour, a piece of brightly glazed pottery appeared as I scraped with my trowel. Although only a few centimetres across it was nonetheless striking given the colours of its glaze; an orangey-yellow and warm reddish-brown, as vivid perhaps as when it was a whole piece of pottery in use however many centuries ago.

Colour, in this example, becomes for me a vehicle for a more empathetic engagement with the past (a theme central to my work). The colour of the sky, the apples on the trees, the trees themselves and the grass were one with the colours of this small fragment of pottery, which until that moment had remained hidden for (perhaps) hundreds of years. It was as if, rather than a shard of pottery, a piece of colour (or colours) from a day hundreds of years ago had lain buried in the soil; colours which at once melted back into the world from which they’d been estranged so long .

Pulling this shard from the almost monochromatic soil, was like looking at an old black and white photograph, where one imagines colour then movement. And looking up at the chapel, at the world moving all around me, I could, in that split second, glimpse the mediaeval past, acknowledging that that distant time was (although very different) just like the world today; there were colours and movement, experienced by individuals just like me and whoever had used whatever the fragment had once been a part of.

A little later as I continued to dig, I found a leaf inside my trench which had blown in from the side. The colours were very similar to that of the pottery (although they have darkened since). And once again this link between the past and present came to the fore. I was thrown back to a mediaeval autumn and imagined autumn in that very spot centuries ago. Like a chain reaction, I imagined the buildings, the road nearby, the walk into town. What was Oxford like at the time as the world moved towards the winter?

This single leaf (pictured above) is pregnant with the passage of time, the unrelenting march of time through another year, towards its end. The colours are like a sunset; the end of a year, the end of a day. But after night comes morning and after winter, the promise of spring. This idea of a continuous cycle seems embodied in both the leaf and the shard. One is young, the other very old – they turn or move in different ‘orbits’ – but nonetheless, in their colours, they have something in common; something I have in common with the individual who owned the pottery (from which the fragment comes) centuries ago; that is, we are part of the same world.

New Work in Progress (WW1)

Projections

Having completed my last stitching project based on trench maps from World War I, I decided to try and superimpose some postcard portraits onto them, of soldiers headed for the Front. In the first (below) I used the photograph of a family which I ‘projected’ onto the map as shown hanging on a washing line.

What strikes me about this image as a whole, is the contrast between now and then as it exists in the contrast between the black and white of the photograph and the colour of the day. This colour, and the sense of the nowness of the present, helps strengthen my own empathetic feelings towards those long since lost – and all but forgotten – to history.

The fact the map hangs on a line like an item of washing, also reinforces the sense of domesticity which is a theme running through some of the postcard portraits, many of which were taken in the backyards of soldiers (or their parents), where evidence of the everydayness of domestic life is in abundance.

One such photograph shows a young couple who’ve recently been married. They stand, unsure of what the future brings, both wearing a look full of apprehension, staring into the lens of the camera, as if this ‘clock for seeing’ as Barthes once referred to them, really could show them the future.

The image onto which their portrait has been projected shows the reverse side of the map, where the threads used to stitch the past together hang like the cut threads of countless lives.

GPS Pot

Just as I’ve been working using stitched fragments of canvas (to convey the idea of the past as being a reimagined collection of pieces ‘stitched’ together in the mind) I’ve also started using pottery; creating pots and cracking them, using lines based on GPS data.

The vocabulary of the ‘find’ is what interests me; the fragments of movement (which the shards of pottery reflect) reassembled to create an approximate whole. It’s new work and the following images are first attempts (the pieces have yet to be dried and reassembled) using a coil pot built with self-drying clay.

No doubt subsequent pieces will be much more refined, using bigger pots and more detailed GPS data.

Radio Interview at Bartlemas Chapel

The following interview was recorded with me as part of an outside broadcast at Bartlemas Chapel in East Oxford on 29th September. You can read more about the dig here (Archaeology in East Oxford website) and on my own project pages, Artefact.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- …

- 32

- Next Page »