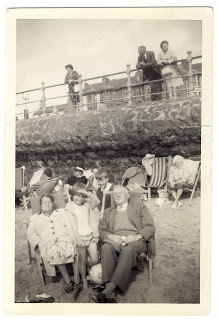

Two postcards and a photograph recently purchased.

Review of Mine the Mountain: Nottingham, UK

By Amanda Mitchell, Nottingham Visual Arts

www.nottinghamvisualarts.net/review/apr-10/mine-mountain-nicholas-hedges

A journey into memory, an acknowledgement of lives that have long since passed, but through their words and images these lives are still very much present in Nicholas Hedges’ Mine the Mountain. There is a sense of passed time and historical presence, a constant reminder that the people you are viewing in the photographs have now gone, leaving me with an eerie sense of voyeurism. Hedges’ collections of photographs represent a lost time and a lost generation. The photographs work together to create a new piece of work, viewed as a whole, not as individual.

The work is in response to the artist’s visits to historical sites, including Auschwitz and Ypres. Hedges draws upon his feelings and thoughts whilst visiting these places to create pieces such as Mine and Correspondence. He is influenced by the impact of sites that have memories of historical trauma as he starts to relate his ideas with his own ancestors in the Welsh mines. With this work he is finding a way to remember people who can be traced back and shown to have existed, if anonymously, as many of the workers at this time were illiterate and would sign their name with a simple ‘X’. This becomes a recurring theme throughout the work; a divider in the postcard piece, a marker for the grave of an unknown soldier.

As an exhibition spectator I feel methodically steered through the work, by the detailed descriptions of the development and history of the pieces, each clearly titled. Although an important contextualisation, I feel almost dictated to, with no room for personal interpretation.

There is much tenderness and sadness inherent in the works as Hedges approaches and deals with this challenging history sensitively; in one piece he uses extracts from the diary of a soldier in the trenches during World War I. The soldier has not been identified, the words are poetic and melancholic, he is a man resigned to his fate. This piece is an acknowledgment of the sacrifice he made, and the sacrifice made by millions of others like him.

This exhibition is a commemoration of the past, a perhaps forgotten story told through provocative photographs and text, it moves and informs you and you cannot leave feeling the same as you did when you entered the exhibition.

Deckchairs

The Book of Disquiet

“Taking nothing seriously and recognising our sensations as the only reality we have for certain, we take refuge there, exploring them like large unknown countries.”

Fernando Pessoa

The Victorians

Today I discovered, much to my delight, that The British Library has on its website a database of 19th century newspapers including 100 years of Jackson’s Oxford Journal. From 1800-1900, every issue is available and fully searchable. It goes without saying how incredibly useful this is and no sooner had I logged on than I began to search for information about my ancestors, in particular those whose activities I have described in previous blogs.

Perhaps the most notorious of my ancestors is Elijah Noon, who murdered his wife Charlotte with a sword in Oxford in 1852. I dealt with this crime at length in an installation which I put on in the cemetery where Charlotte was buried (see www.nicholashedges.co.uk/murder for more information) but soon discovered, thanks to The British Library, a whole lot more that I would never have otherwise found.

The website also allows users to download articles or pages as PDFs. Those about the murder are available here:

Murder of a Wife by her Husband (8th May 1852)

The Recent Murder in Oxford (17th July 1852)

I’ve read these stories before, but in another article, I discovered that a nephew of Elijah’s had recently been killed in a railway railway accident at Bicester, not so far from Oxford. Elijah’s older brother, Thomas Noon, was a builder in Oxford and a man who it seems was very much respected. Having searched for news of an accident some time around 1852, I discovered that Thomas Noon’s son, also called Thomas, who was a Corporal in the 7th Company of Royal Sappers and Miners, had been killed in a railway accident on 6th September 1851. He was buried in the same cemetery (St. Sepulchre’s in Jericho) in which his aunt would be interred less than a year later, his funeral attended by ‘an immense concourse of persons.’

Frightful Railway Accident and Loss of Life at Bicester (13th September 1851)

Notice of the Funeral of Corporal Noon (13th September 1851)

Elijah Noon served just two years in prison for the murder (or ‘manslaughter’) of his wife. In 1880 and 1882, he is listed as a prize-winning ‘bird-fancier’.

One article I was shocked to read concerned a fight which took place in Summertown on 29th December 1869. The article reads:

“Elijah Noon and George Hedges were fined, the former 7s. 9d. and the latter 10s. 6d. for being drunk and riotous at Summertown on 29th Dec. last. P.C. Culverwell substantiated the accusation and stated that the defendants were stripped to fight, when he stopped the disturbance going on.”

Petty Sessions (19th February 1870)

The Elijah Noon in this story is the son of my great-great-great-grandfather, Elijah Noon Sr. who of course we know murdered his wife. George Hedges is my great-great-grandfather who married Elijah’s sister, Amelia in 1869, not long before the fight took place. What it was all about, of course I cannot say, but it seems that both George Hedges and Elijah Noon Jr. were often in trouble.

Elijah Jr. had something of a drink problem. In September 1883, William Francis Piggott of Summertown applied for the renewal of his licence, which it seemed had been revoked on account of Elijah’s drunkeness.

Licence Renewal (8th September 1883)

Elijah of course had had a traumatic childhood having witnessed the murder of his mother at the hands of his own father. It seems his was an unhappy life, one which ended tragically when he choked to death in The Grapes, George Street in 1885 (click here to read more).

What George’s excuse was I don’t know, but he was, as I’ve said, often in trouble. In 1861, at the age of 15, he was already in attendance at the Petty Sessions in County Hall. In 1867 he was sentenced to 21 days hard labour for stealing wood and in 1888, fined for a disturbance, again in Summertown.

George had a brother called Edwin. Their father, my great-great-great-grandfather, was called Richard, and in 1858, a Richard and Edwin Hedges were convicted of an assault on a certain John Harris. Whether this Richard and Edwin are my ancestors is debatable, but it would seem to concur with George’s general behaviour, and indeed that of the family. One story, which certainly involves George and indeed, it seems, the whole family, took place in Summertown in 1899. It’s described under the rather inappropriate heading of ‘Family Squabble’ and involves William Bowerman, who married Elizabeth Hedges – George and Amelia’s daughter – in 1894.

Bowerman and Elizabeth had been drinking in the Cherwell Tavern, Sunnymede when ‘there was a quarrel’. Elizabeth went to her parents’ house where she was followed by her husband. He knocked on the door, Amelia answered and Bowerman, so it was alleged, punched her in the face. Her son Harry and her husband George went out to ‘remonstrate.’ Bowerman hit them both and Harry hit him back. The scan of the report is a little ‘wonky’ but it can be read here.

Interestingly, I have a photograph of my ancestors taken in 1899 – one assumes before the brawl.

I have (tentatively in some cases) identified them as follows:

(Top, left to right) Harry Hedges, Ernest Edges (my great-grandfather), Lily Bowerman (?), William Bowerman (?), George Hedges (my great-great-grandfather), Alfred Hedges

(Middle, left to right) Flo (Alfred’s wife) (?), Amelia Hedges (my great-great-grandmother), John Lafford (my great-great-grandfather), Alice Hedges, (?), Percy Hedges

(Bottom, left to right) Richard Hedges, Margaret Hemmings (nee Hedges), Margaret V Hemmings (on knee), Alice M Hemmings (on feet), Ellen Hedges (nee Lafford) (my great-grandmother), Winifred May Hedges (on lap), Eliza Hedges (nee Villebois), Jack Hedges (on knee), Olive Hedges (at feet), Elizabeth Bowerman (nee Hedges), Eliza M Bowerman (on knee), Ernest G Bowerman (at feet).

Art Must-Sees this Month

Mine the Mountain is listed on Culture24.org‘s list of Must-See Art shows this month. I’m at No.3, just below Richard Hamilton… can’t be bad!

The Answer

For years the answer to a question I’ve been asking myself has been staring me in the face. Its own face is a big ugly one on the cover of a book which I used to have and which I loved to read and play as a child.

I won’t say anymore for now, so again this entry is one that will, for the time being, make sense only to me.

Wordsworth and The Other

On my journey back from Nottingham yesterday, I listened to a podcast of In Our Time about William Wordsworth’s The Prelude. Whilst listening to one of the panel talking (Stephen Gill) I was struck by his reading of a particular passage and what he said about it thereafter. The passage was from Book II of the poem and is as follows:

The garden lay

Upon a slope surmounted by the plain

Of a small Bowling-green; beneath us stood

A grove; with gleams of water through the trees

And over the tree-tops; nor did we want

Refreshment, strawberries and mellow cream.

And there, through half an afternoon, we play’d

On the smooth platform, and the shouts we sent

Made all the mountains ring. But ere the fall

Of night, when in our pinnace we return’d

Over the dusky Lake, and to the beach

Of some small Island steer’d our course with one,

The Minstrel of our troop, and left him there,

And row’d off gently, while he blew his flute

Alone upon the rock; Oh! then the calm

And dead still water lay upon my mind

Even with a weight of pleasure, and the sky

Never before so beautiful, sank down

Into my heart, and held me like a dream.

Stephen Gill said of this passage: “look at the language of this, it’s all about your body being taken over by the outside world, the dead still water lays upon thy mind, the sky sinks down into my heart and the pleasure of it all is a weight.”

I was struck by this passage and commentary as it seems to parallel the notion of the embodied mind; a corporeal consciousness engaging with the world through the physical body.

I bought a copy of The Prelude and read the first few lines which served to illustrate this point further:

Oh there is a blessing in this gentle breeze

That blows from the green fields and from the clouds

And from the sky: it beats against my cheek

And seems half conscious of the joy it gives.

The following passage is a lovely description of the act of wayfaring:

Whither shall I turn

By road or pathway or through an open field,

Or shall a twig or any floating thing

Upon a river, point me out my course.

In a piece I wrote on my website about history, I wrote the following:

In his book The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology, Christopher Tilley writes: ‘The painter sees the tree and the trees see the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter, become part of the painting that would he impossible without their presence. In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects. Dillon comments: “The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”’

I am interested in how the landscape remembers the people it ‘sees’ and I find this ‘Other’ everywhere in Wordsworth’s poetry. Again in Book I of The Prelude.

How Wallace fought for Scotland, left the name

Of Wallace to be found like a wild flower,

All over his dear Country, left the deeds

Of Wallace, like a family of Ghosts,

To people the steep rocks and river banks

In Lines Written A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth addresses his sister Dorothy with the following words:

Therefore let the moon

Shine on thee in thy solitary walk;

And let the misty mountain-winds be free

To blow against thee: and, in after years,

When these wild ecstasies shall be matured

Into a sober pleasure; when thy mind

Shall be a mansion for all lovely forms,

Thy memory be as a dwelling-place

For all sweet sounds and harmonies; oh! then,

If solitude, or fear, or pain, or grief,

Should be thy portion, with what healing thoughts

Of tender joy wilt thou remember me,

And these my exhortations! Nor, perchance,

If I should be where I no more can hear

Thy voice, nor catch from thy wild eyes these gleams

Of past existence, wilt thou then forget

That on the banks of this delightful stream

We stood together

I like to think of this poem and this passage as addressing nature herself, that great ‘Other’ which remembers those whom she has seen.

Ancient Reflections

I went to the Ashmolean Museum today and found myself literally in the surface of an Athenian, black-glazed hydira (water-jar) dating from around 400 B.C. My reflection in the glaze became for a moment a part of its design and I wondered as I looked at my silhouette, who else had become a part of its fabric over the course of the last two millennia?

Text Rain

The following image is taken from Tom Phillips’ book, Postcard Century. I was reminded on looking at the image of a piece I made called Dreamcatcher and in particular a photograph I took of work in progress.

Future Work

Mine the Mountain 2

This weekend I set up my latest exhibition at Surface Gallery in Southwell Road, Nottingham. It’s a lovely space run by a great group of people (all volunteers) who helped install the show – to them I am very grateful indeed! Below are some photographs of the exhibition. More information on the exhibition can be found on the Mine the Mountain website.

The exhibition runs until 19th March 2010.

Dust Motes II

Two photographs taken from the archives of the Czechoslovakian secret police and two photographs from a piece of mine called Broken Toys.

Interesting Link

An English Journey Reimagined

www.guardian.co.uk/books/video/2010/mar/03/english-journey-iain-sinclair-alan-moore

An Act of Imagination

There’s a shop in Paris where I like to go, whenever I am there. In a box you can rummage through a small pile of photographs, miscellaneous images, nothing overly special, but for a few Euros one of them can be yours. That shown below is the last one I bought.

The photograph is small; two and a half by three and a quarter inches. It’s damaged and indistinct; blurred in parts, but nonetheless one can see the interior of a church, within which a small group of women and girls stand facing towards the altar. The photograph was taken from above, perhaps from a gallery opposite the pulpit which one can see on the opposite wall. The pulpit’s draped in material, whether that’s normal or for a special occasion I cannot say. I cannot tell what is going in, but clearly something’s happening beyond the frame of the picture (the world is happening beyond the frame of the picture – as are we, the viewer). As for a date; given the hats, I would say it was taken sometime in the 1920s.

The photograph is fragile. It has the feel of an Autumn leaf, dried and picked from the ground the following Spring. When I hold it in both my hands, my thumbs discover very slight depressions where others have looked before me. The way the paper’s warped, the way that it bends, tells me it’s been looked at many times.

Where the picture contains the trace of someone who was loved, the paper carries the gesture of the lover.

Of course we cannot know this, not for certain. But history is an act of imagination.

Who is the object of his or her attention? My eyes move to the girl at the front, dressed in white or pale colours and wearing a matching hat. My left thumb, in its slight depression almost seems to touch her, mimicking the gesture of the one to whom it belonged. There’s something secret about the image, as if whoever took it shouldn’t have been there, shouldn’t have possessed her. It’s an image that’s meant to be kissed, secreted away in a wallet. Affection has caused the wear in the corner.

She knows she’s being photographed. She knows that someone loves her. She can see in her mind’s eye the gallery behind. She can sense the gaze of her admirer. But then the paper tells me she didn’t turn around, she never returned the gaze. Ever.

A Well Staring at the Sky

The title of this piece takes its name from a passage in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet;

“We never know self-realization. We are two abysses – a well staring at the sky.”

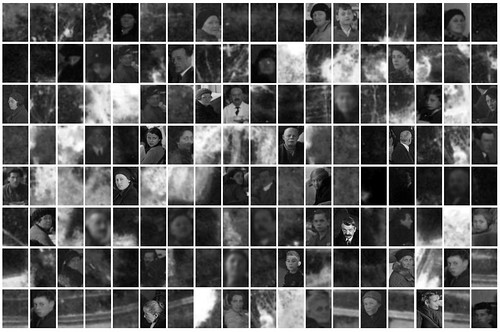

For me, this quote describes the act of looking at a photograph, at people in the past who are likely no longer with us. I look at them from a time when they do not exist, and they look at me from a time when my existence was wholly unlikely. They are reflections left in the water of the well, and I, for the moment am the person looking in. The portraits in the work are from a single photograph taken in Vienna c.1938. The faces are mixed with images cropped from an aerial view of the Bełżec Death Camp photographed in 1944. History too is a well staring at the sky. Again in the well’s water, we see the sky reflected with some of its stars and all of its gaps. But no gap is truly empty and all the holes in what we call history are full of traces; the residue of a glance perhaps shared between two people.

To see more work from this exhibition, please follow this link.

In Ruins

“A ruin is a dialogue between an incomplete reality and the imagination of the spectator.”

Christopher Woodward, In Ruins

Photograph of Corfe Castle taken during a school trip in 1983.

I first visited Corfe Castle in the summer of 1978 whilst on holiday with my family. I was 7 at the time. I can remember a postcard commemorating the murder of Edward the Martyr (reigned 975-978) a 1000 years before. It’s the first historic place which really captured my imagination, and ever since my mind’s been in thrall to the past. The idea of a 1000 years ago seemed – as it does now – impossible, and in the museum below, in the village of Corfe, I remember staring at a cannon ball dating from the English Civil War, trying in my mind’s eye to picture it, as it was at the time of the siege, moving through the air.

Photograph of me and my brother at Corfe Castle c.1980.

Dust Motes

Mine the Mountain 2 – Poster

For more information, please visit www.nicholashedges.co.uk/minethemountain

Mine the Mountain 2

Postcards are a kind of conversation, inasmuch as they’re a connection between two places; one that’s unfamiliar and one that’s known. That’s not always the case of course, but their form’s a framework – a metaphor – with which I try to engage with the past.; to find its lost, anonymous individuals. ‘The Past is a foreign country’, wrote the author L.P. Hartley in the first line of his novel The Go-Between. Whatever information we receive about that place, whether in writing, an object, a painting or a photograph, it comes like a postcard from a foreign shore.

Postcards are fragments, pieces of a world which has vanished, often carrying information of little or no consequence. In the translator’s foreword to The Arcade’s Project, Walter Benjamin’s ‘monumental ruin,’ we read:

“It was not the great men and celebrated events of traditional historiography but rather the ‘refuse’ and ‘detritus’ of history, the half concealed, variegated traces of the daily life of ‘the collective,’ that was to be the object of study.”

The ‘collective’ is represented in this exhibition by the sheer number of postcards and the pictures which they make when grouped together as a whole. What their component images say, echoes my attempt to find the individual so often subsumed, both in unimaginable numbers and the history which we read in books or know through film and television.

In photographs we often come closest to finding individuals when – ironically – they’re distant, when they’re blurred and unaware of the picture being taken. These are genuine moments of history. With words, it’s often the smallest of details which brings the past alive, for in these parts the whole of the time from which they’re now estranged is immanent.

Tom Phillips, in the preface to his book ‘The Postcard Century’ writes that with postcards:

“High history vies with everyday pleasures and griefs and there are glimpses of all kinds of lives and situations.”

High history sits in every word, even in the ‘x’ of a single kiss. Or the words in the postcard below; prices for Train, Ale and Fags.

A postcard too is often the physical trace of a journey, one connecting the dots from the place in which it was posted to its final destination. But this destination’s never really reached, and as such, a conversation which may have begun 100 years ago, is never finished. We read the words today, written before we’d ever the hope of existing, sent by those who don’t exist anymore.

The images in this exhibition are not ‘genuine’ postcards per se, but they are (for the most part) postcard-sized, inspired by a collection dating from the First World War. It’s the idea of the part (the individual image) as being a part of a whole which interests me and the whole being immanent in the part, just as humanity is immanent in every individual.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- …

- 32

- Next Page »