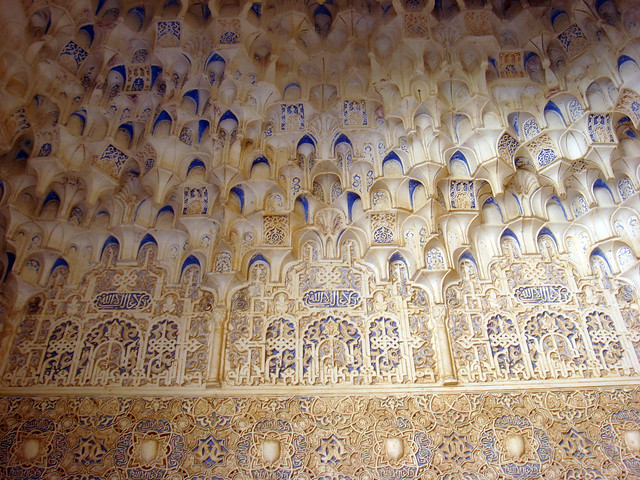

For more than 700 years, from 711 to 1492, there was an Islamic presence in Spain, and for that, in the 21st century, with the legacy of its beautiful architecture, we can only be grateful. After all these years, the stunning buildings with their beautiful interiors still retain the power to beguile, and certainly, the Moorish sights of Andalucía are without doubt, amongst the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.

From the well-preserved ruins of ancient baths in Granada and Ronda, to the strange and somewhat schizophrenic Mezquita in Córdoba, the sights reach their zenith in the awe-inspiring perfection of the Alhambra palace. The craftsmanship of the Islamic artists responsible for its creation are, I believe, quite without equal, and with every step and every space within, the sense of wonder increases, as if playing pass the parcel where you win every turn, unwrapping an increasingly bigger prize.

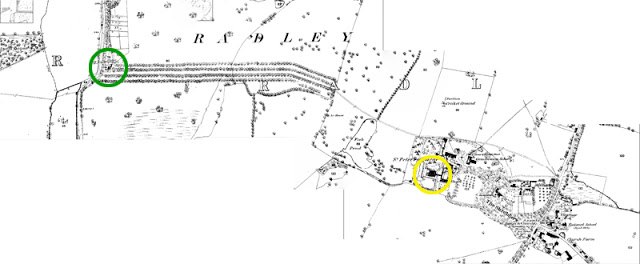

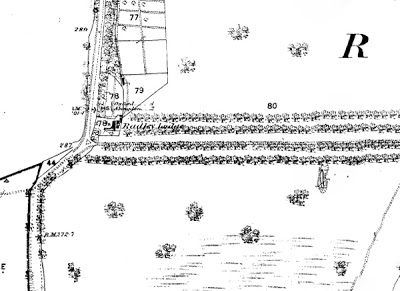

Built in the 10th century by Abd ar-Rahman III of Córdoba, the city of Medinat al-Zahra existed for less than a century, when in 1010 it was destroyed during a civil war. In 1911, the ruins were discovered buried beneath the earth and since that time 10 per cent of the site has been uncovered.

Given what we’d seen in the rest of Andalucía, we had high hopes for the ruins. Of course we weren’t expecting another Alhambra or Mezquita – far from it – but what we found was, in our minds, a disaster.

We arrived first at the new visitors centre, a low profile, modern building – all crisp lines and angles – in which we got our free ticket, used the loo and bought fridge magnets. There was, as far as I could see, little else on offer, and it seemed to me that apart from the shop and the toilet, it was little more than a glorified bus stop. It maybe that in hindsight, I’m being particularly unkind, but the very shape of it, its very contemporary feel, all found an unwelcome resonance at the top of the hill, in the ruins of the Medinat al-Zahra.

Having arrived on the bus and walked through the gates, we found ourselves with a view of the ruins, and at that moment our hearts sank. Everything was orderly, neat and clean, with far too many straight lines. We walked on, down concrete paths into what remained. The walls had been tidied up and neatened with concrete slabs, so that far from the tumbledown walls peppered with flora which make ruins so special, and which for centuries have delighted artists, writers and philosophers, visitors are presented with a series of modern facsimiles, of, amongst ther things, walls and gates.

Whole parts of the site have been ‘restored’, which is to say destroyed. Ruins of course are by their nature evidence of destruction. What we see in a ruin is the destructive passage of time as well as perhaps evidence of some historic trauma. Of course, the site has to be excavated, and again, by definition, archaeology – to some extent – destroys. But there is a huge difference between excavation and preservation on one hand, and restoration – or rather rebuilding – on the other. What visitors are offered at the site of Medinat al-Zahra isn’t the chance to see with their imaginations what it might have looked like 1000 years ago. Instead we are spoon-fed a vision of what someone else thinks it might have looked like.

On the Andalucía website, the following passage about the ruins speaks volumes:

To visit Madinat al-Zahra today does not mean entering an archaeological site where imagination has to make up for lack of volume. In al-Zahra, the huge amount of fragments found over many years of excavation made the experts seriously consider the question of how to present them. A museum would have meant metres and metres of display cabinets. Finally, it was decided to assemble the pieces of each palace over huge models at a scale of 1:1. This enable today’s visitors to perfectly visualise the setting for the tales of chroniclers and poets of the caliphate’s time.

It is then a model. Nothing more.

This response to what is a very important arcaheological site is rather like taking the recording of a song on a wax cylinder made in the late 19th century and embellishing it with new voices, new instruments and so on. While following the same melody, the new recording will ultimately drown out the original. Instead of listeners using their imaginations to enter the world of the 19th century room where the recording was made, and to hear how the voices would have sounded by using their experience of sound today – and there by doing become a part of that original moment – we get instead, nothing more than a replica.

Perhaps the most deplorable part of the extract from the Andalucía website is the first line: To visit Madinat al-Zahra today does not mean entering an archaeological site where imagination has to make up for lack of volume. It’s as if using one’s imagination is seen as bad, or at best a chore. You don’t have to do any of that here! We do it for you!

Imagining the ruins in our own minds, as they once might have looked, creates the space for us to imagine ourselves there. We’re never going to be able to recreate them as they really were, but that’s not the point. It does become a point however when someone tries to imagine them for us. As Christopher Woodward writes in his book ‘On Ruins’:

“A ruin is a dialogue between an incomplete reality and the imagination of the spectator…”

Furthermore, a city isn’t just a series of streets and buildings, it’s as much about the people who live there, who walk the streets, stand around, looking, chatting, getting on with their everyday lives. With ruins, in particular the ruins of cities, we have not only the fragmentary remains of physical structures, but the fragmentary remains of people – not in terms of their physical remains, i.e. their bones, but their movements.

This movement is bound up with what I call sightlines (and sightlines in turn with movement, for when we observe something, we do so as much with our bodies as our eyes). If you can imagine that when you look at something, the light between you and the thing observed remains once you’ve turned away, then we can imagine that bound up in every fragment within a ruin are hundreds and thousands of these lines.

In Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, we read:

“From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star. A sort of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze – light though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.”

When I look at the stones of a ruin, I’m sharing a similar skin with everyone who’s seen it.

In his novel Invisible Cities, the writer Italo Calvino writes of a city:

“Something runs among them, an exchange of glances like lines that connect one figure with another and draws arrows, stars, triangles, until all combinations are used up in a moment…”

In another extract:

“…there runs an invisible thread that binds one living being to another for a moment, then unravels, then is stretched again between moving points as it draws new and rapid patterns…”

Every place contains remanants of these threads which we can then pick up, and when we pick them up, we become for a moment part of one of these long since vanished patterns.

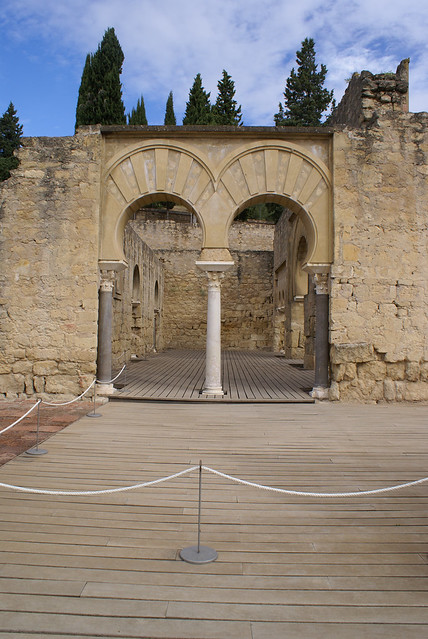

The picture below shows a reconstructed arch at the site.

The following shows an arch which hasn’t been (completely) rebuilt, part of which still rests on the ground.

When I look at the remains on the ground, I imagine the sightlines associated with them. I imagine the people who would have looked at the arch every day – at those very stones lying on the ground. And by looking up at the gap where it once was, my body in some way mirrors that of the person looking centuries ago. The sightlines, as if they’re strings, become taut, and for a split second, a moment in the distant past is recovered. Part of a pattern (as Calvino describes) is restored; the dead light piled on the ground lives again.

A few years ago I described my view of history in terms of the cloning of dinosaurs in the film Jurassic Park. I explained how I took what fragments remained of a particular time or event (for example the old stones of a ruin) and filled the gaps with my embodied imagination. Embodied imagination in this instance, is an imagination anchored in the real world – in the sensory world around us. People in the past knew how it felt to feel the wind on their face; they saw the same sky and the clouds. They knew how it felt to have a body. In other words, it’s not a pure flight of fancy. It is just as Christopher Woodward explained – a dialogue. Not a monologue. We are not being dictated to by the ruins, and we are not dictating to them. Instead we are talking together, and it’s in this conversation that we find an authentic view of the vanished past.

At the Medinat al-Zahra however, what we experience is a monologue, but one which is spoken not by the ruins – but by those who have chosen to rebuild it. The gaps in the ‘DNA’ are filled not by our imaginations, but by concrete. Imagine a conversation between two people, with a third person – quite unknown to the others – shouting over the top of them. That is what it’s like here.