During Walk No.4 I discovered a sign entitled ‘Undermined’ about the coal industry in Newcastle. Given the importance of coal to the area, I’ve reproduced the information below in its entirety.

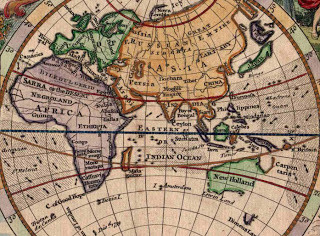

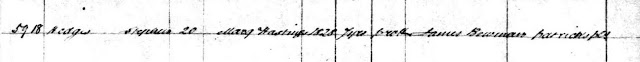

‘Awabakal clans used Newcastle’s coal in their fires and ceremonies for millennia, and explain its origins in their ancient Dreaming stories. Europeans also sought this valuable substance, so when Lieutenant Shortland noted coal deposits here in 1797, shops were quickly dispatched to return quantities of coal to Sydney. In 1799 The Hunter exported a shipment of coal to Bengal, and Newcastle coal was later shipped to the Cape of Good Hope by the Anna Joseph.

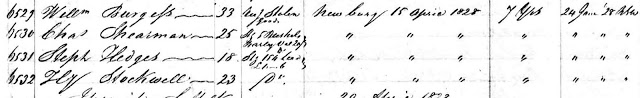

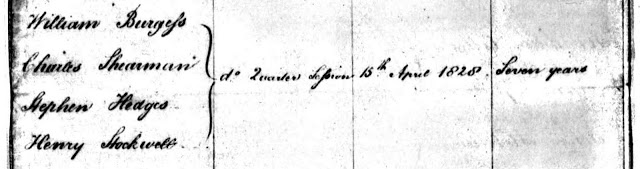

During the early years of settlement, the Colonial Government declared Hunter River coal to be the property of the Crown and prohibited free individuals and companies from mining here. Convict gangs were obliged to work the coal seams and load the vessels.

In 1826 private enterprise was finally permitted to mine coal and the Australian Agricultural Company obtained the first lease. In 1831 the company sunk its initial shaft near the Anglican Cathedral and innumerable tunnels chasing the buried coal seams have since been excavated below Newcastle’s streets. The success of the Australian Agricultural Company soon attracted other companies and mining operations spread to the extensive coalfields of East Maitland in 1844.

Fast-loading steam cranes were installed at King’s Wharf in 1860. But the demand for coal still exceeded the loading capacity of the port so the Bullock Island mud flats were reclaimed and new coal loading wharves were constructed. In 1888, twelve hydraulic cranes were in position.

During the late nineteenth century, sailing vessels berthed two or three deep along the length of the Bullock Island dyke, creating a forest of masts, while hundreds of sailors of all nationalities flocked to the city of Newcastle on Saturday nights. Throughout the twentieth century, further developments in mining and loading saw Newcastle’s exports soar, and by 1907 coal shipments exceeded 4,500,000 tons.

The port of Newcastle has long been the economic and trade centre for the Hunter region. In the 1989-90 financial year Newcastle handled 68.2 million tonnes to become the world’s largest coal export port and Australia’s largest tonnage dock.’