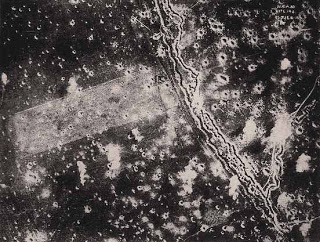

Anyone who has stood on the edge of the Lochnagar crater at La Boiselle in France, cannot help but be overawed by its vast size. The result of a huge mine, detonated below ground at 7:28am on 1st July 1916 (the first day of the Battle of the Somme), the crater is almost 300 feet in diameter and 70 feet deep.

“The whole earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up in the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earth column rose higher and higher to almost 4,000 feet. There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like the silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris.” The words of 2nd Lieutenant C.A. Lewis of No. 3 Squadron RFC who witnessed the blast.

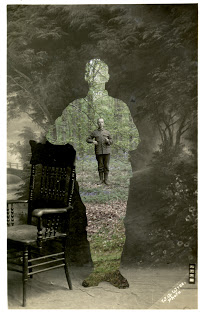

Thinking more on this, I had in my mind’s eye an image of the past receding – a past moving away from us here in the present-day. I thought about sound and how, as it moves away, its pitch shifts due to the fact its wavelength stretches (what’s known as the Doppler effect). I thought then about light, how as it moves away, its wavelength stretches and shifts towards the red end of the spectrum. It’s through this redshift that scientists can deduce how far away an object (such as a star) is from the Earth and how fast it is travelling. Redshift is often used as a way of explaining the Big Bang. If you imagine the Big Bang (or indeed any explosion), you can easily visualise how everything emanating from within it would move away from its centre. Everything we see in space today is a result of that first explosion. As a result, everything is moving away – something we can see in the redshift of distant galaxies.

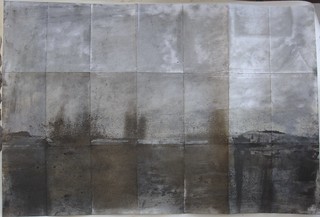

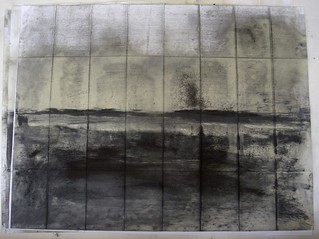

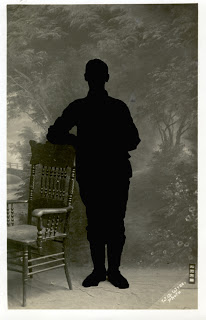

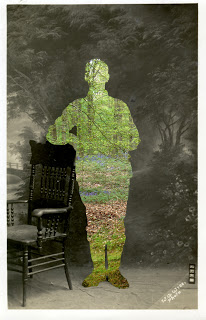

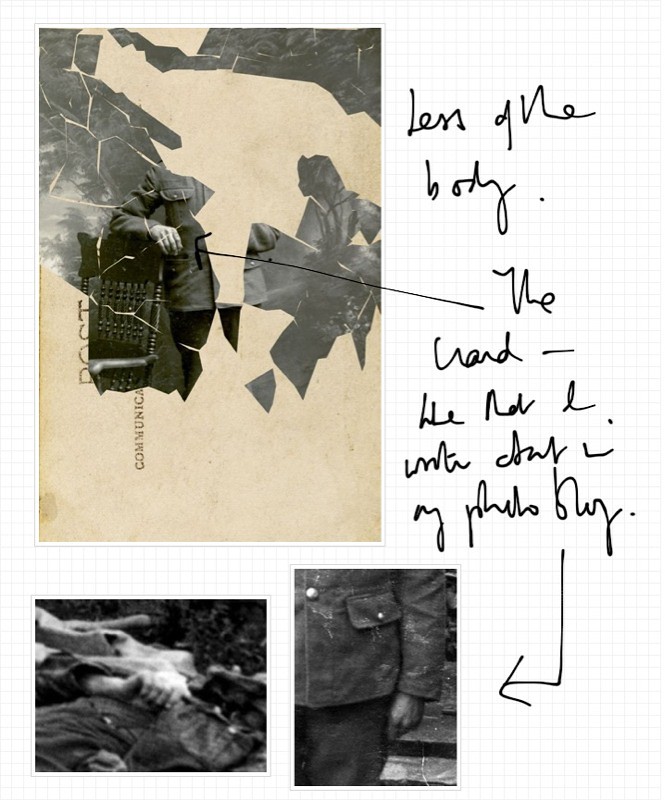

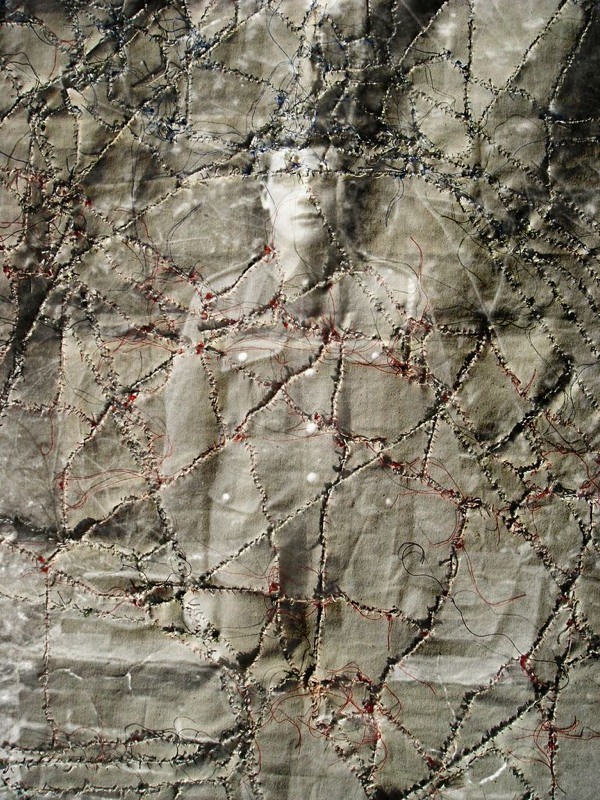

As we move away from the catastrophic events of World War I, and as we approach its centenary, the craters and shell-holes that pockmark the old Western Front, become – like the trenches – filled with earth. They become grown over with grass, flowers and trees; and this gradual retreat towards the natural world is, I think, a kind of redshift in the landscape.

I want to explore this idea and to think more about an audio piece I’ve been working on: a recording of my mum and aunts singing Where Have All The Flowers Gone in 1962.