First thoughts on Graham Sutherland, ‘An Unfinished World.’ Modern Art Oxford

|

| Graham Sutherland, Dark Hill – Landscape with Hedges and Fields, 1940. Swindon Museum and Art Gallery © Estate of Graham Sutherland |

In his excellent book, ‘A History of Ancient Britain,’ historian Neil Oliver writes:

“All of Britain was a work in progress as nature set about reclaiming the land. The period of hundreds of thousands of years known to archaeologists as the Palaeolithic – Lower, Middle and Upper – was over. The remote world of the mammoth-hunters of Paviland, even the lives and times of the Creswell artists and the butchers of Cheddar Gorge belonged to the past. The ice of the Big Freeze had drawn a line that separates them from us, then from now.”

This line in our history, this schism carved through time in much the same way as valleys were carved and gouged by ice from rock, is a place I find myself observing when I look at some of Sutherland’s haunted landscapes. They are silent spaces, from which it seems humankind is quite estranged; banished even. In some, it’s as if Man has yet to appear, as if the world is part of a parallel universe, similar in some respects, but altogether different. There are, as well as those landscapes which seem divorced from knowable time (from history), landscapes from the recent past; ruined prospects of towns wracked by war. And while the source of this ruination is Man himself, the sense which Sutherland creates is one in which Man again ceases to exist. It’s almost as if through both types of landscape (those we might – very loosley- describe as rural on the one hand, urban/industrial on the other), Sutherland is reminding us that for the unimaginably greater part of its existence, the world did not know us; that for the equally ‘impossible’ span of time that stretches ahead, the world will have no need of us either.

This sense of oblivion haunts Sutherland’s landscapes; Earth’s indifference towards us – in the grand scheme of things – permeates almost every canvas and drawing, no matter how small. They each seem to echo the wonderful words of the 17th century writer Sir Thomas Browne, when he writes in ‘Urn Burial.’

“We whose generations are ordained in this setting part of time, are providentially taken off from such imaginations. And being necessitated to eye the remaining particle of futurity, are naturally constituted unto thoughts of the next world, and cannot excusably decline the consideration of that duration, which maketh Pyramids pillars of snow, and all that’s past a moment.”

On some of Sutherland’s drawings, the artist has drawn a grid of horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines. Grids like these would often be used when scaling drawings up to full-size works, and perhaps that is what the artist intended them for. When I see them however, I see them not as something detached from the work itself – a mere tool for reproduction – but rather an integral part of the work. It’s as if the artist is trying either to order the chaos which he’s rendered on the page (and which he’s no doubt observed in the real world), or do battle with Man’s certain oblivion and relative obscurity, imposing his mark on the landscape; his dominion over the world.

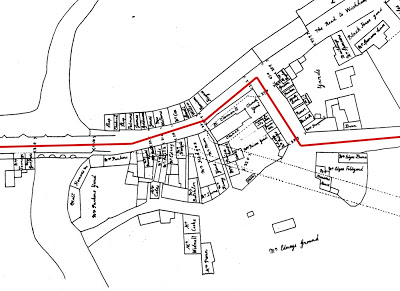

|

| A Farmhouse in Wales 1940. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales |

If the Farmhouse in Wales above is slowly dissolving back into the landscape, then perhaps it can be seen as a metaphor for man’s own ineveitable fate. The grid therefore, this means for scaling up, for seeing more clearly and in greater detail (the bigger picture as it were) is perhaps then a means for trying to understand that fate, for comprehending those ‘pillars of snow,’ so beautifully described by Browne in 1658.

|

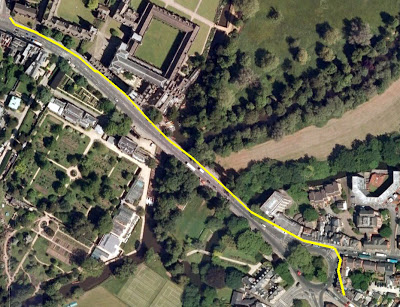

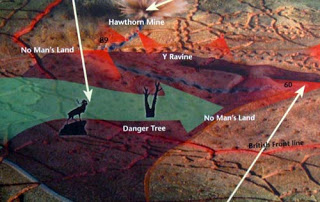

| Welsh Landscape with Yellow Lane 1939-40. Private Collection, London |

In a video to accompany the exhibition, curator (and artist) George Shaw, describes how the use of yellow gives the appearance of a landscape which is jaundiced; perhaps sick. I however see this sickness not as a part of the landscape, but a part of our own vision of ourselves; our place in the ‘grand scheme of things.’ Even where Sutherland has painted machines (which by their very existence would seem to point towards the existence – and therefore relevance – of mankind), there is still the sense of Man’s complete absence from the world. It’s as if, as I’ve said, these paintings depict those two great and awful spans of time, between which Man’s existence is pressed, like rocks beneath the vast sheets of ice, which once crawled and covered this place we call home. (Even those gargantuan glaciers – in places almost a mile thick – which smothered the country for so many thousands of years, would seem like Browne’s ‘pillars of snow’ when considered against the backdrop of eternity.)

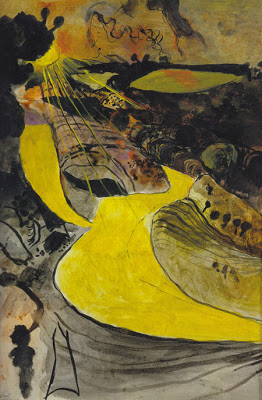

In the exhibition’s first few paintings, we find these same desolate landscapes, replete with standing stones (for example, in ‘Sun Setting Between Hills’ below) such as those found at ancient sites throughout the country.

|

| Sun Setting Between Hills 1937. Private Collection |

At once these landscapes become charged with mystery, and like those paintings which show, for example, cranes gorging themselves on the landscape, we are presented with evidence of Man’s existence. The standing stone and the ruined urban landscape, mirror one another. Poles apart, they seem to delineate this landscape in which we, for a short time, have strutted the stage of our existence. No-one is likely to walk the yellow roads which cut through the world above – yet someone must have been there.

|

| Interlocking Tree Form 1943. The Whitworth Gallery, University of Manchester |

Despite this apparent absence of Man, the trees in some of Sutherland’s landscapes seem almost human, at least in their gestures. Some such gestures echo the agonies of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, (for example, in ‘Interlocking Tree Form’ above) while ‘Study for a Blasted Tree,’ calls to mind Goya’s ‘Disasters of War.’

|

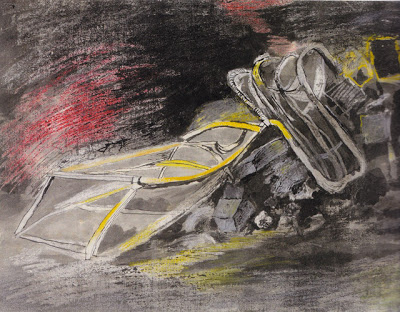

| Fallen Lift Shaft 1941. Junior Common Room Art Collection, New College. |

It was whilst looking at the painting above, that I found myself thinking of William Blake. In this work, ‘Fallen Lift Shaft,’ there is a small patch of red which is reminiscent of some of the poet’s own paintings. The lift is on the one hand a casualty of war, a victim of Man’s aggression. On the other it’s a symbol of his descent. It is perhaps the Fallen Angel.

The exhibition is titled ‘An Unfinished World‘ and whilst reading Richard Dawkins’ book ‘The Ancestor’s Tale,’ I found a quote, which for me encapulsates what that title means. The world, with or without Man, is always unfinished. Dawkins writes:

“The second connected temptation is the vanity of the present: of seeing the past as aimed at our own time, as though the characters in history’s play had nothing better to do with their lives than fore-shadow us.”

In other words, we are not the end, just as we weren’t the beginning. And it’s this conceit which Browne cautions against in his meditation on death discussed above. Sutherland’s landscapes are for me, the equivalent of trying to imagine one’s own non-existence in a world which is always, as Neil Oliver writes, ‘a work in progress,’ one in which nature will one day set about reclaiming from Man.

One might think it’s possible therefore to view Sutherland’s paintings as a warning against this conceit. But to do this is in itself a kind of conceit. The fact is, we are just another part of the landscape. The yellow road was there before us, and after us the yellow road rolls on. Sutherland’s paintings are not warnings, but statements of fact.

And while this might sound somewhat depressing, another quote from Dawkins (again from ‘The Ancestor’s Tale’) might just lift our spirits:

“As physicists have pointed out, it is no accident that we see stars in our sky, for stars are a necessary part of any universe capable of generating us. Again, this does not imply that stars exist in order to make us. It is just that without stars there would be no atoms heavier than lithium in the periodic table, and a chemistry of only three elements is too impoverished to support life. Seeing is the kind of activity that can go on only in the kind of universe where what you see is stars.”

|

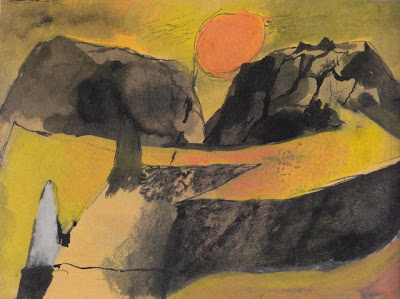

| Landscape 1969. Harry Moore-Gwyn (Moore-Gwyn Fine Art) |

In many of Sutherland’s works, our very own star, the sun, is present such as in the work above. In one of the first paintings within the exhibition, to the last (painted just four years before his death- see below) the same sun is in view.

|

| Twisting Roads 1976. Private Collection. |

And we – like Sutherland – can only see it, we only know it, because we exist.

Perhaps therefore, in Sutherland’s work, humankind is in evidence after all.