I’ve discussed previously, three extracts from newspapers in which a moment of silence serves to amplify all that happened before and after. To recap, those three extracts were [my italics in all]:

“On Sunday last, at the close of the evening service, the Society Meeting was held, and references to the death of Private Rogers were made by several members of the Church. Private Rogers’s mother is one of the oldest members of the Church. The meeting passed a vote of condolence with the relatives, all present standing in silence.” (1915)

“Shortly after dusk, the lightning appeared in the south and western horizon, and soon became most vivid, blue sheets of lightning following each other in rapid succession, but unaccompanied by thunder.” (1842)

“Her mother got up and tried the door but it was locked by [the] witness when her father and mother came in. Her father took the sword out of the sheath which he threw to the floor and then struck her mother on the back with the flat side of sword; neither her father nor mother spoke.” (1852)

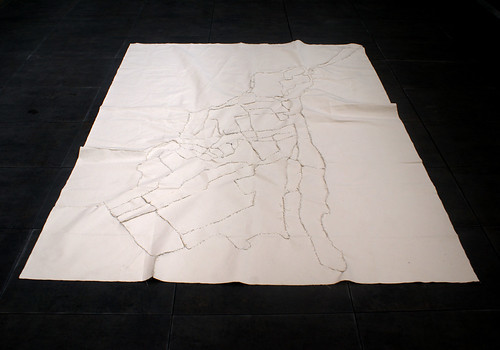

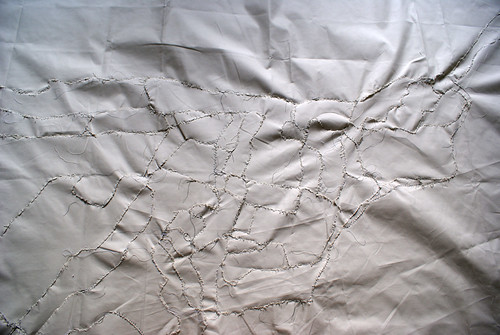

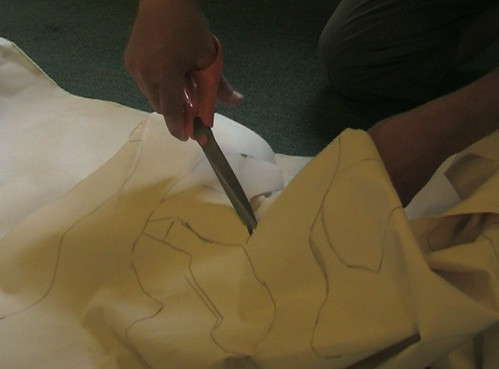

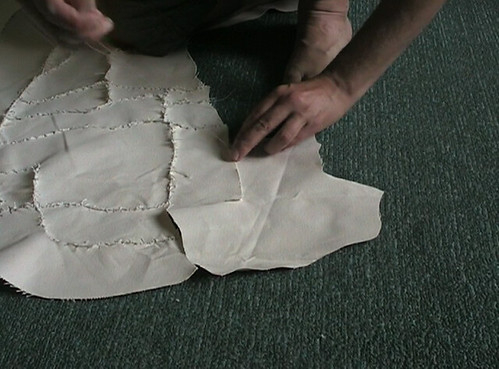

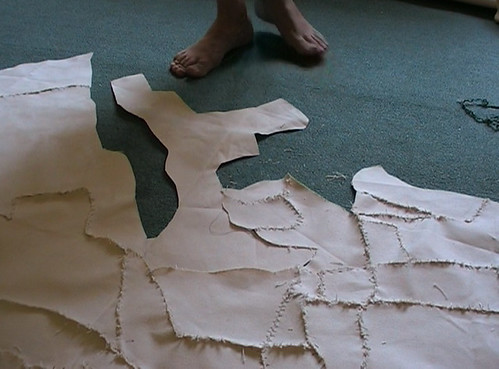

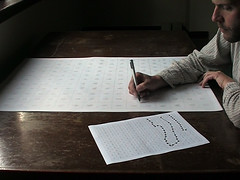

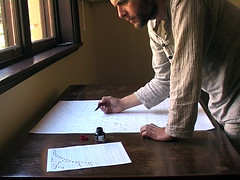

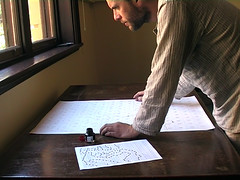

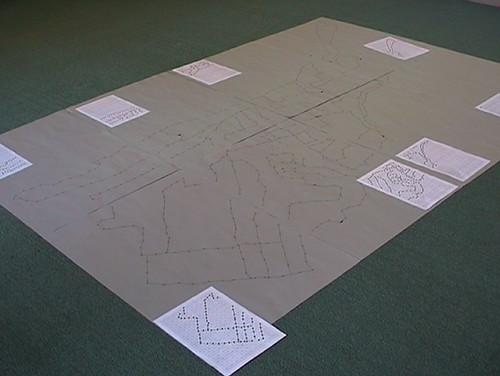

In each of these three passages, the moment of silence is set in opposition to the text preceding it, and, as a result, it serves, as I’ve said, to amplify that text. As I was thinking about this, I became aware that the pieces of work, Heavy Water Sleep and The Woods, Breathing also reflected this opposition.

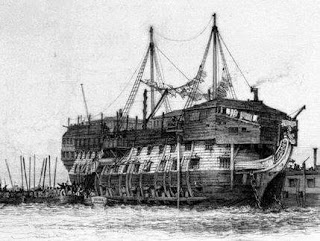

Both projects use a moment in the life of Adam Czerniakow. As I’ve written before:

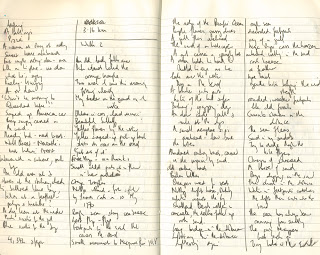

“For almost three years, Adam Czerniakow was ‘mayor’ of the Warsaw Ghetto. One of the inspirations for this work is a line taken from his diary, which he kept whilst living in Warsaw in occupied Poland from 1939 to his death in 1942. On September 14th 1941 he wrote:

‘ In Otwock. The air, the woods, breathing.’

On occasion, Czerniakow was allowed to leave the ghetto to visit the Jewish Sanatorium at Otwock just outside Warsaw. It was one place he could find some respite from the horror and torment he endured in the ghetto.”

In reading his diary, this effort and the toll which it took on both his physical and mental health is evident and in these few words – the air, the woods, breathing – words with which we can easily identify, we can glimpse his relief at being able, just for a short time, to stand in the woods and breathe. In that simple, everyday, action we see the other side of his life; the world far beyond our own comprehension.

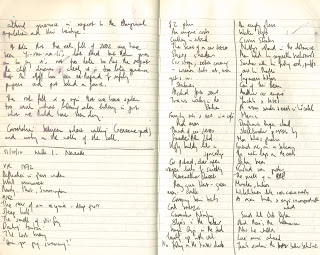

Czerniakow would also seek solace in reading. One night, on January 19th 1940, he wrote:

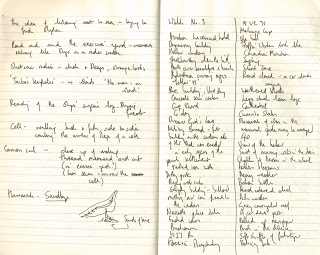

“…During the night I read a novel, ‘Pilgrims of the Wild’ – Grey Owl… The forest, little wild animals – a veritable Eden.”

Given what we know about the Holocaust and what Adam Czerniakow went through, these silent moments – in the woods at Otwock and reading at home – are set in stark contrast to what was going on around him. As a result, these two moments serve to amplify the horrors of the war; everything that had happened and everything that had yet to occur.

In my previous blog, I quoted Jorge Luis Borges who wrote:

“A single moment suffices to unlock the secrets of life, and the key to all secrets is History and only History, that eternal repetition and the beautiful name of horror.”

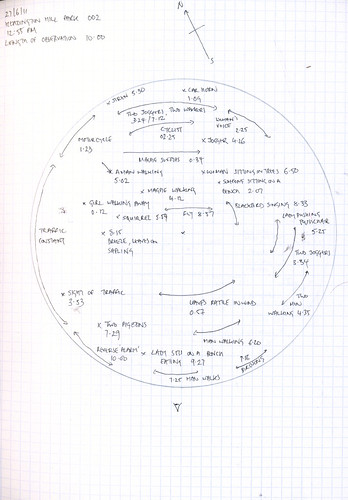

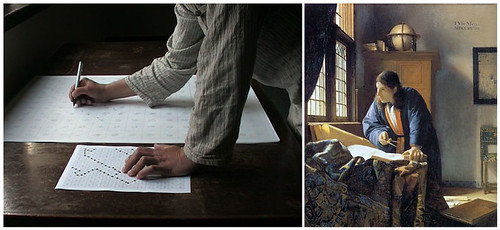

The word moment crops up a lot in my work, as it has in this entry. I’ve long thought that one can only empathise with people in the past through an awareness of present day moments – moments of the everyday. Borges’ quote seems to bear this out. In the case of Adam Czerniakow I have given two such moments. Then there are the three moments of silence in the passages above.

History is a cycle, an eternal repetition of single moments. When I read the same book that Czerniakow read (Pilgrims of the Wild) I am repeating that same single moment. Likewise, when I stand in a wood I am repeating another of those single moments.

So the silence amplifies History and the nature of that silence serves as a moment of connection with the past. The nature of silence and its opposition to violence is interesting too. I return to a favourite quote of mine:

“…if the opposite of war is peace, the opposite of experiencing moments of war is proposing moments of pastoral.”

Peace equates with pastoral, and, perhaps, with silence. I shall end with a quote from Rilke which also seems to fit with what I’ve been saying:

“Look, trees exist.

The houses we live in continue to stand. Only we

pass away like air traded for air and everything

conspires to maintain silence about us, perhaps

half out of shame, half out of unspeakable hope.”