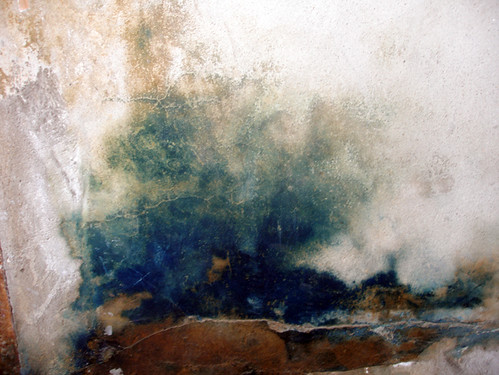

Having completed one side and a corner of the installation ‘prototype’, pasting approximately 300 A4 drawings onto my studio walls, I believe that my initial concerns about the sizes of the individual drawings may be unfounded. In fact, as the walls have dried, and more images have been pasted on top of one another, the overall effect is as I’d first envisaged it.

Working in a corner has been important in this respect, as I can get a better impression of how the whole room will come together. The next stage will be adding in the string.