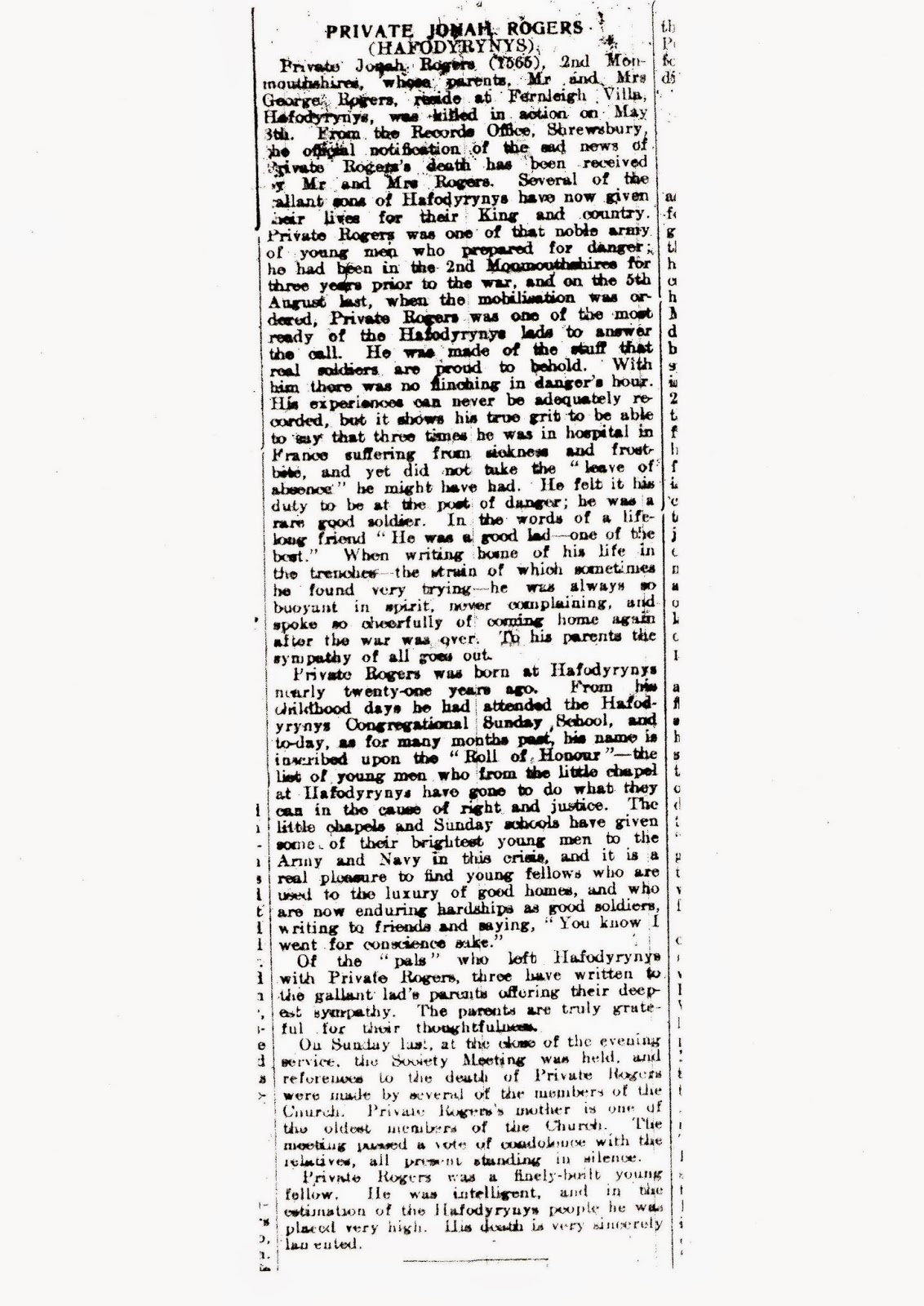

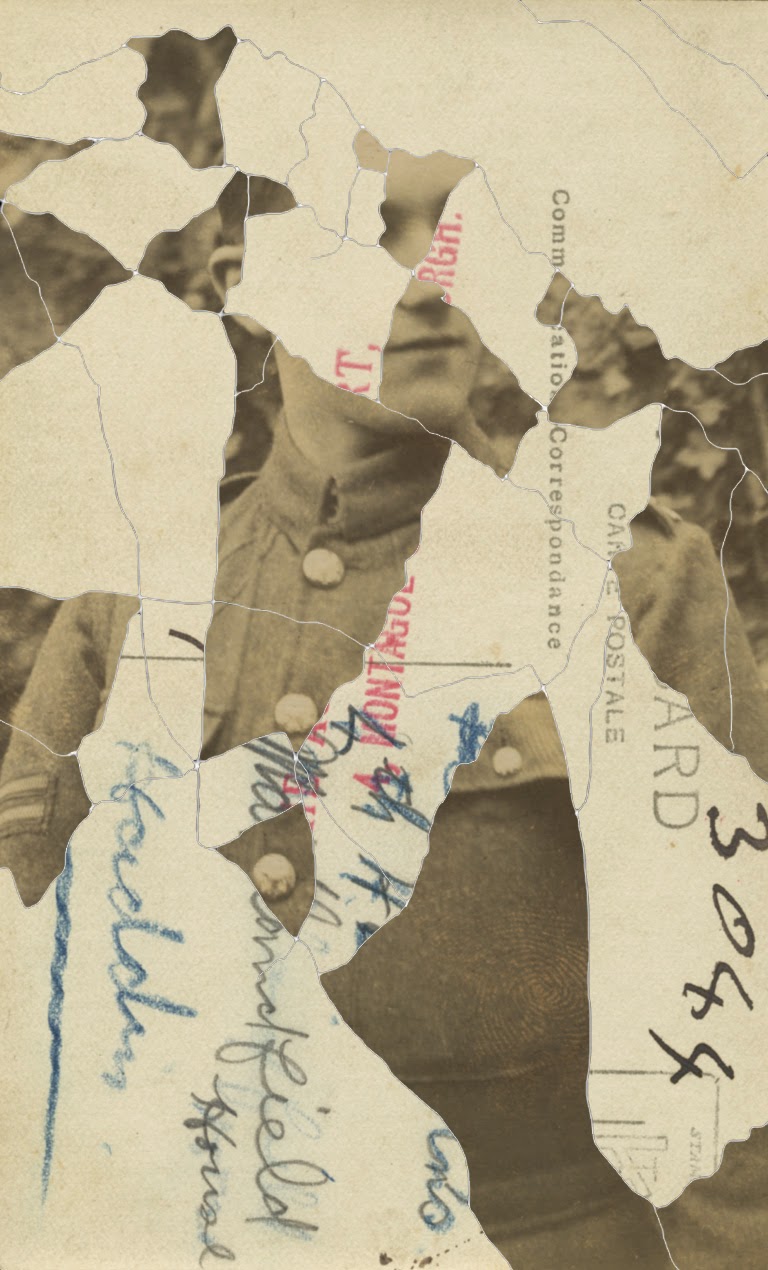

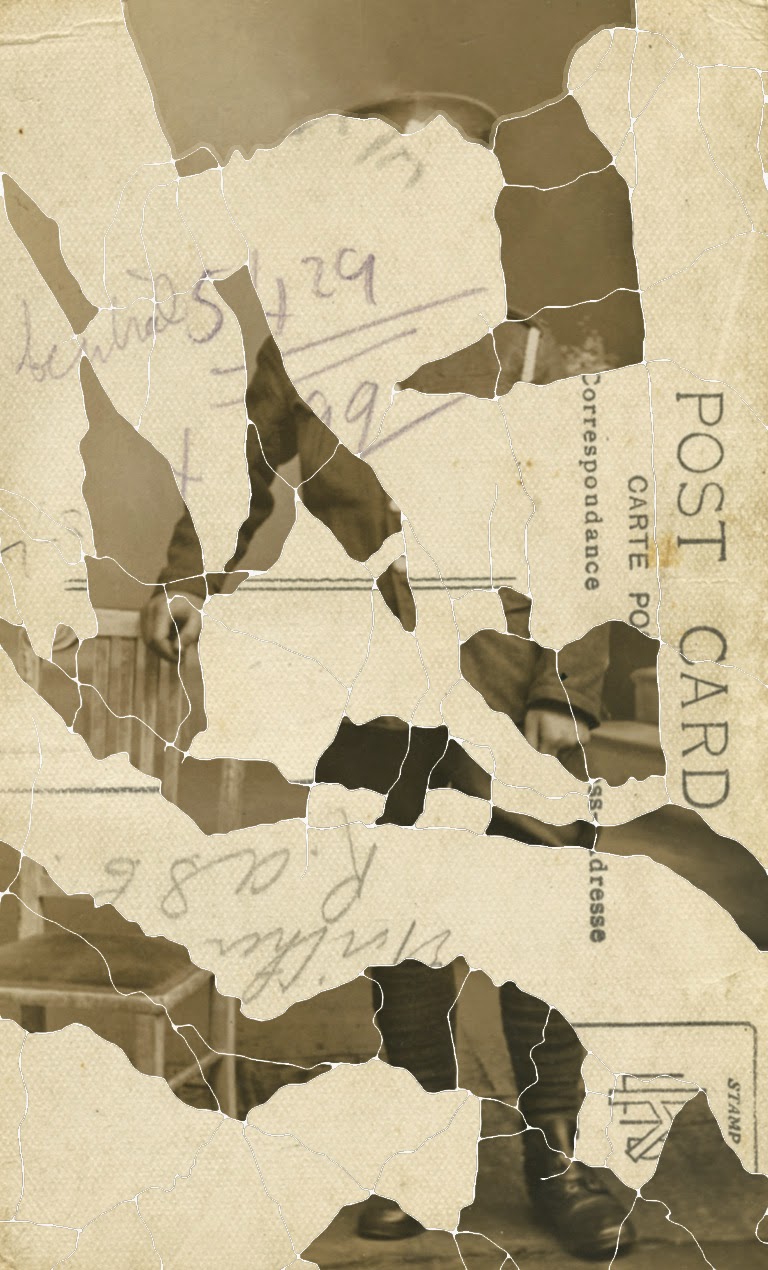

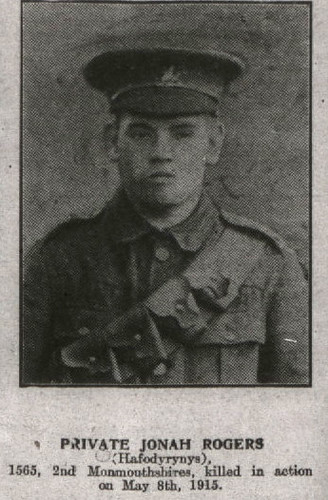

100 years ago, on 8th May 1915, my great-great-uncle was killed in the Second Battle of Ypres.

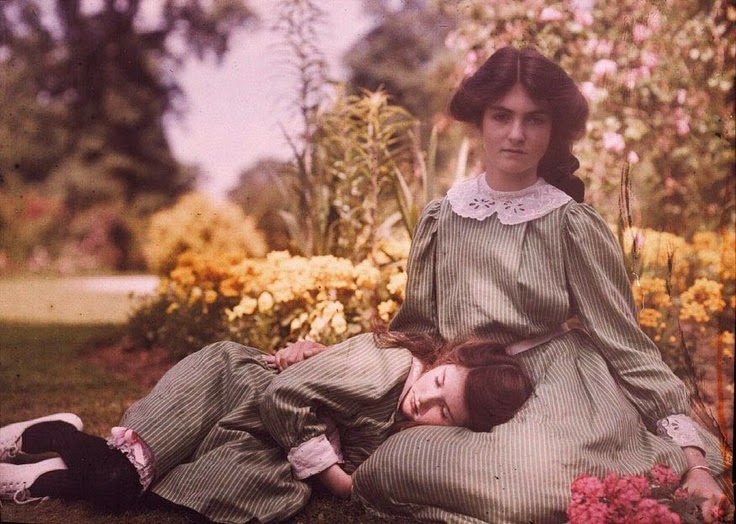

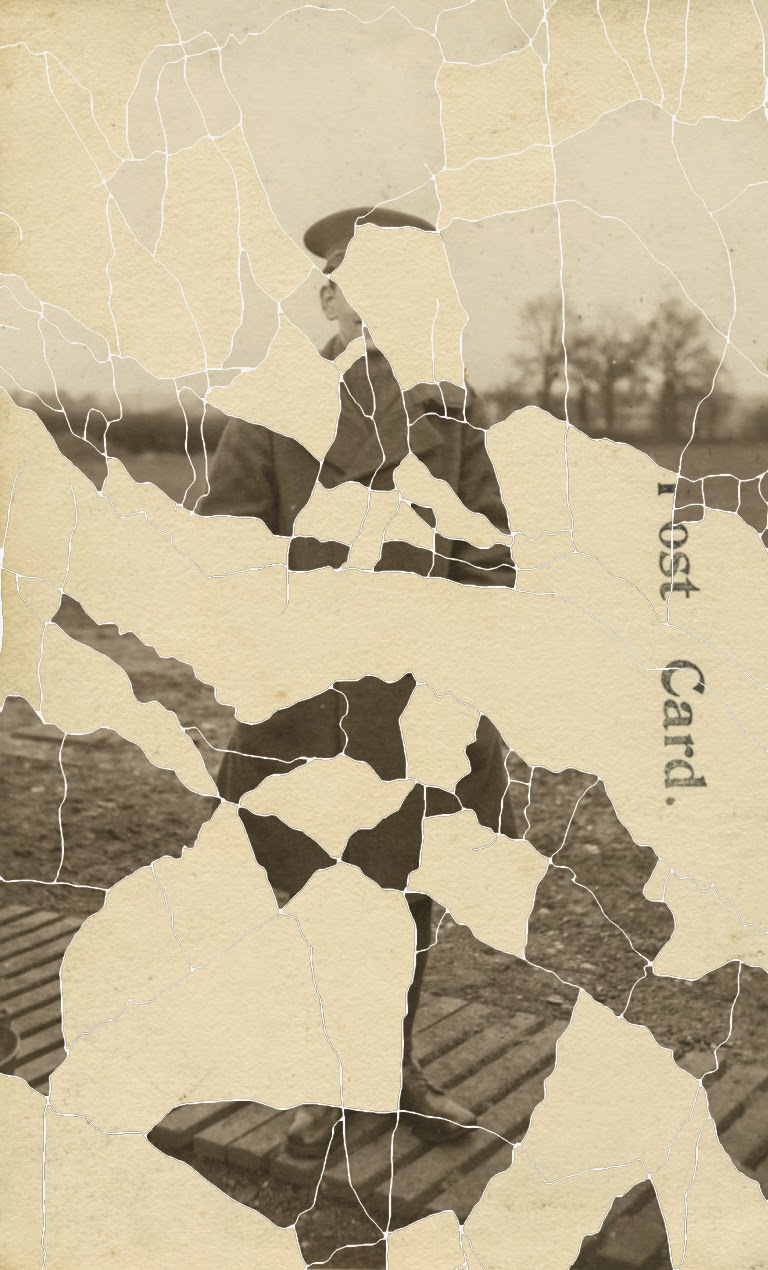

I’ve written before about this photograph and in particular its location; the idea of the garden as a shared space of memory and experience. Recently, in our own garden we had to have an apple tree taken down due to the fact it had been hollowed out by heart-rot and was in danger of toppling over. I asked for the trunk of the tree to be save in one piece, and when I saw it on the ground, I was reminded again of the idea of gardens as described above.

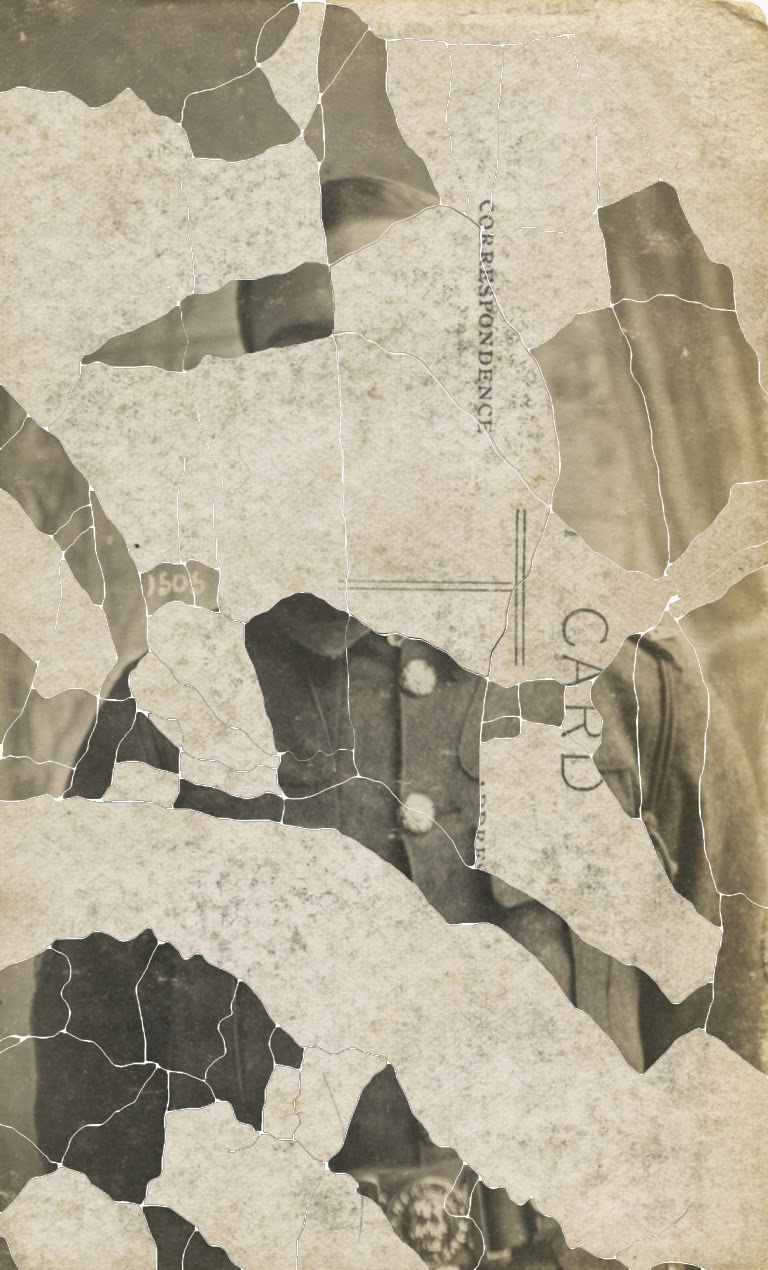

The trunk of the tree resembled a torso missing its head and limbs.

There was something interesting in the way the bark had grown over a length of wire which had been wrapped around the trunk years ago. It called to mind the cascading lengths of barbed wire rolled out in front of the trenches. It also seemed to turn the trunk into a corpse.

At the same time the tree Is symbolic of a lost idyll; that of the garden of childhood memories.