During this week of Remembrance, a few days after the 90th anniversary of the end of the First World War, I’ve been thinking about how it is that an event which happened almost a century ago still holds such a powerful draw on our consciences today. What is it that makes the Great War seem anything but distant when events which proceeded it only by a few years seem twice as far in the past?

In the last couple of days I’ve been continuing my research into my great-great-uncle Jonah Rogers, who was killed on the 8th May 1915 at the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge.

I have now been able to locate the positions he held as part of the 2nd Monmouthshire Battalion, on the day of the battle, being as they were part of the 12th Brigade in the 4th Division (thanks to Martyn Gibson and David Nicholas for their help with this).

In a ‘History of the 2nd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment,’ compiled by Captain G.A. Brett, D.S.O., M.C., I read the following account of the battle in which Jonah lost his life.

“By the 8th May the British had withdrawn from the most advanced points of the Ypres salient, and the Germans, striving to obliterate the salient completely, made further determined efforts to gain ground. Desperate fighting ensued, the six days, 8th to 13th May, of the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge, giving many anxious hours to British commanders. When the storm broke the Battalion was on the right of the brigade still holding Mouse Trap Farm…”

Looking at a diagram of the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge, one can see clearly where the Battalion would have been stationed; to the left of the 84th Brigade at Mouse Trap Farm.

The more I ‘get to know’ Jonah, the more the war as an historic event, changes. Whereas before I could only know it as a thing in its own right, an homogenous mass observed from a distance, like a planet in the night sky, now, with a shift in focus, I see Jonah first, and then, through him the war. The telescope becomes in effect, a microscope, with Jonah the lens through which the war, in all its millions of parts, is magnified.

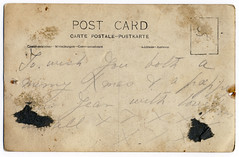

I do not know the exact details of how Jonah died. Given the ferocity of the artillery bombardment and the use prior to this of poison gas, there are any number of possibilities. And although knowing the nature of his death would add to the emotional weight of his story, it is the possibility of pinning down the location of his death which makes more of an impact upon me. It serves to make him – and the war – more vivid, more real. By locating him in the places where he lived and where he died, and by alternating one’s thoughts between the two, one can imagine too his loved ones, shifting their thoughts between memories of him at home and thoughts of him at war. And in that space between – a kind of No Man’s Land – one can locate their fears and their prayers. The same can be said for Jonah, who no doubt during the months he was at the Front, staring across at the enemy, thought a great deal of the place in which he lived.

For his family, left behind in Hafodyrynys, the war could only be imagined but would permeate everything they did. Whatever they did, however mundane, there would be the war. Even in the landscape, in its shape, its colour, its sounds, the war would be contained but never spilled beyond the outlines. And in these shapes and spaces, their hopes and fears would vie against each other.

Perhaps the fact I can share at least some of this space, in the movement of my own thoughts between the place he lived and the place he died, helps explain the reason why, although I know what happened to him, and where and when it happened, I still feel, when reading about the war prior to May 1915, a sense of concern for his wellbeing. If I read any account of the war after the day he died, every word is permeated with his absence. That is not to say I mourn as such (as his immediate family would of course have mourned) but I do sense his absence, I do sense the anxiety of his separation (in the end, eternal separation) from home.

Without a known grave, this separation – his death – must have been all the more difficult for his family. On the gravestone of his older brother, William, who died aged 10 in 1897, the following inscription has been added:

Also of Pte. Jonah Rogers, 2nd Mon Regt. Son of the above Killed in Action in France, May 8th 1915.

Jonah has no known grave, save that within the minds of those of us who remember him. Perhaps then, my concern is for the wellbeing of his memory?

We must all as individuals continue to remember. We must remember that the millions who died in the slaughter, were not an anonymous mass brought into play by History (just as we are not an anonymous mass brought together to remember) but young individuals, taken from their homes and loved ones; individuals to whom we are all related. A million British and Commonwealth soldiers lost their lives in the War. A million graves, known and unknown lay in the fields of Flanders and France. Back home, a million holes, will only ever be filled with the thoughts of those who come after them. Thoughts that pass with our passing. Holes to be filled again by successive generations.