The following passage is taken from ‘The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot’ by Robert Macfarlane. In a chapter on water he writes:

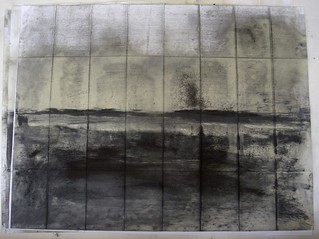

“The second thing to know about sea roads is that they are not arbitrary. There are optimal routes to sail across open sea, as there are optimal routes to walk across open land. Sea roads are determined by the shape of the coastline (they bend out to avoid headlands, they dip towards significant ports, archipelagos and skerry guards) as well as by marine phenomena. Surface currents, tidal streams and prevailing winds all offer limits and opportunities for sea travel between certain places…”

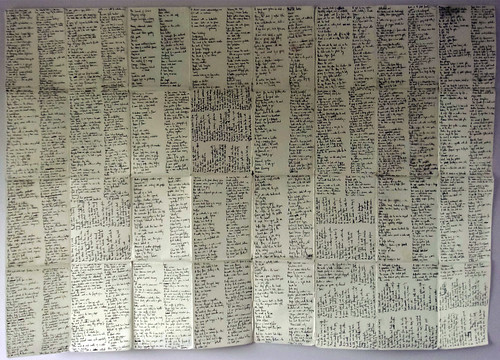

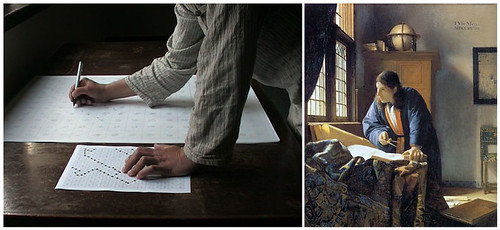

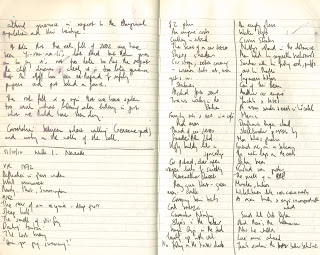

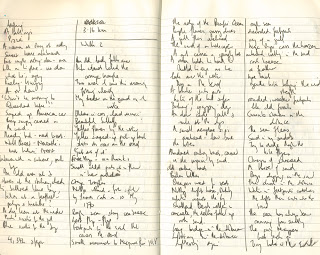

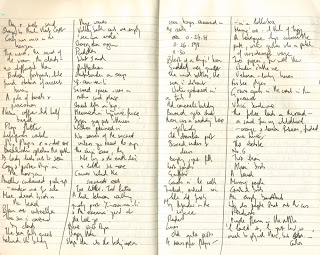

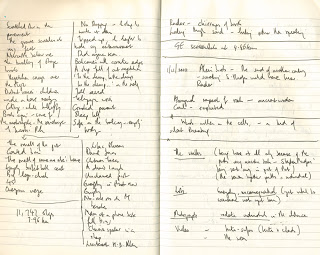

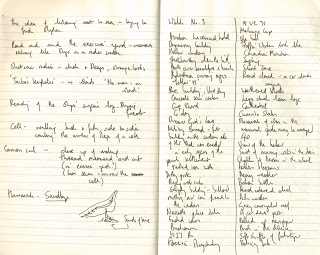

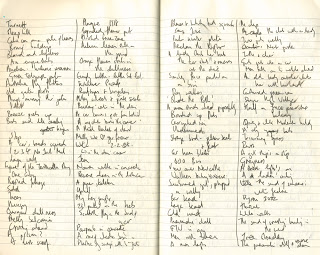

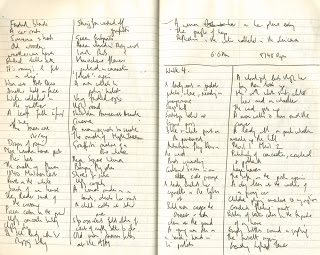

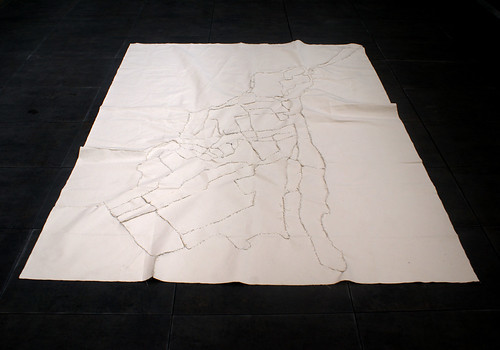

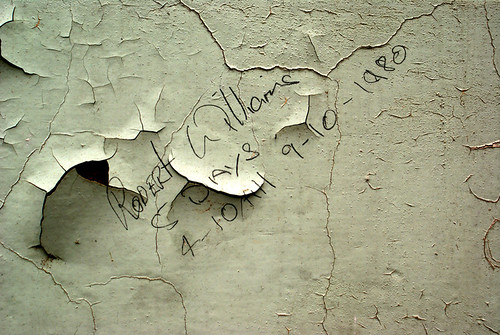

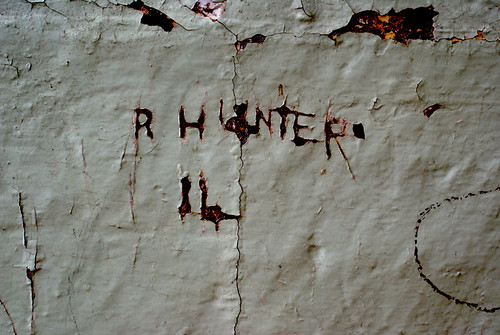

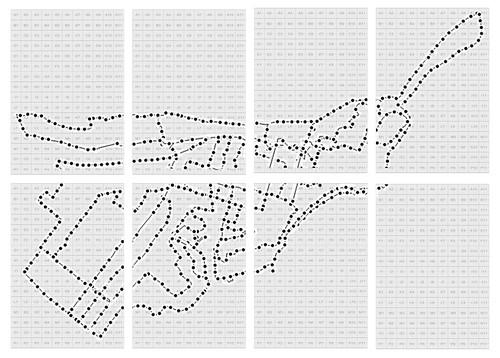

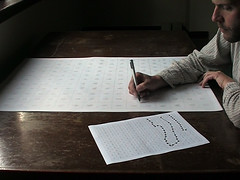

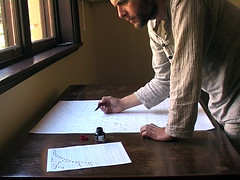

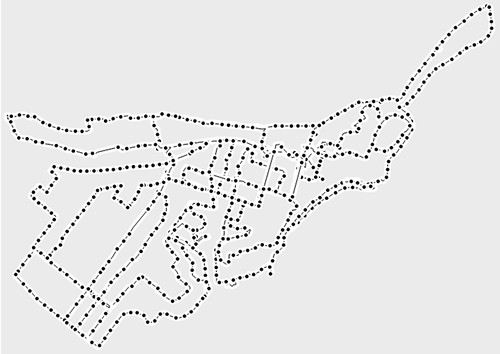

This reminded me of some work I did on my ancestor Stephen Hedges who was transported to Australia in 1828. In particular I thought about the route The Marquis of Hastings (the ship on which he sailed) took from Portsmouth to Port Jackson (Sydney) which I mapped using Google Earth and coordinates written down in a logbook by the ship’s surgeon, William Rae.

Macfarlane also writes:

“Such methods would have allowed early navigators to keep close to a desired track, and would have contributed over time to a shared memory map of the coastline and the best sea routes, kept and passed on as story and drawing…

Such knowledge became codified over time in the form of rudimentary charts and peripli, and then as route books in which sea paths were recorded as narratives and poems…

To Ian, traditional stories, like traditional songs, are closely kindred to the traditional seaways, in that they are highly contingent and yet broadly repeatable. ‘A song is different every time it’s sung,’ he told me, ‘and variations of wind, tide, vessel and crew mean that no voyage along a sea route will ever be the same.’ Each sea route, planned in the mind, exists first as anticipation, then as dissolving wake and then finally as logbook data. Each is ‘affected by isobars, / the stationing of satellites, recorded ephemera / hands on helms’. I liked that idea; it reminded me both of the Aboriginal Songlines, and of [Edward] Thomas’s vision of path as story, with each new walker adding a new note or plot-line to the way.”

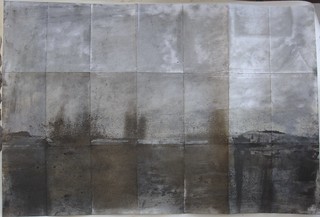

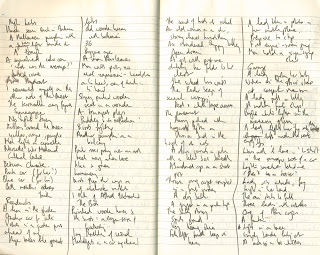

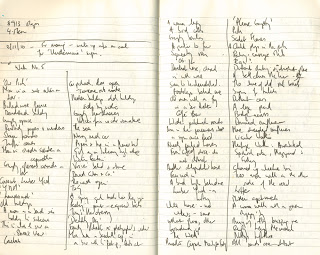

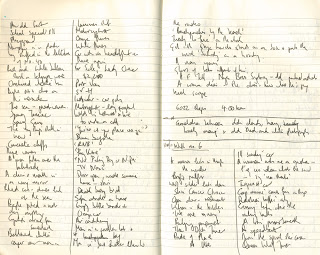

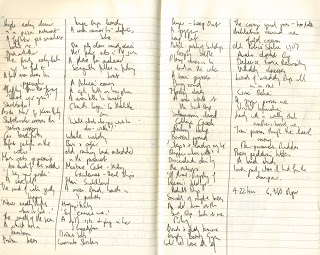

One of the things I like about William Rae’s logbook of the journey aboard the Marquis of Hastings is the description of the weather. The world aboard a prison ship in 1828 is far removed from our experience, but we know weather and can therefore use his descriptions to bridge the gap between now and then; moving from – to use Macfarlane’s words – “logbook data” through “dissolving wake” and “anticipation,” all the way back to “planned in the mind.” The description of the weather therefore becomes a poem of sorts, echoing what Macfarlane writes above; how sea paths become narratives and poems, allowing me to step back into the mind of my ancestor.

Fresh Breeze. Mist and rain.

Strong Breeze. Cirro stratus. Horizon hazy.

Hard gale & raining. Heavy Sea.

Hard rain & Violent Squalls. Hail & rain.