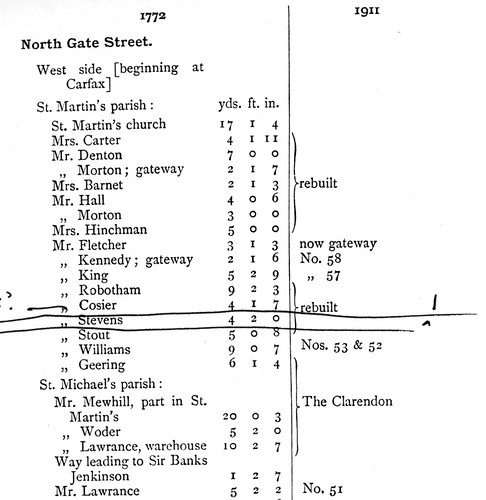

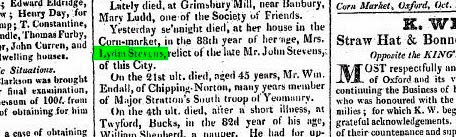

I’ve turned my attention to my 4 x great-grandfather Samuel Stevens who I know was born in Oxford in 1776. I know too that he married a woman called Mary and that they had a child called John (my 3 x great-grandfather) in 1811.

In the library this afternoon I tried to find details of other children they might have had and the date and location of their wedding; however I couldn’t find anything save for details of a daughter, Frances, born in St. Aldate’s Parish in 1809, two years before John. However that was it, which led me to suspect that either one or both had died after John’s birth, or that they had moved away – which seemed the more likely.

Given that John lived in Reading for much of his life, it seemed plausible that it was actually his parents who moved some time after his birth in 1811. Searching through the records online, I eventually found a Samuel Stevens who married a Mary Pecover in St. Lawrence Parish, Reading on May 14th 1807. This I’m sure must be my ancestor; not only does the place fit – along with the name of his wife – but the date of the wedding – two years before the birth of Frances – also fits the wider picture. It seems therefore that having married Mary in Reading, they moved to Oxford but left shortly after to return to Reading.