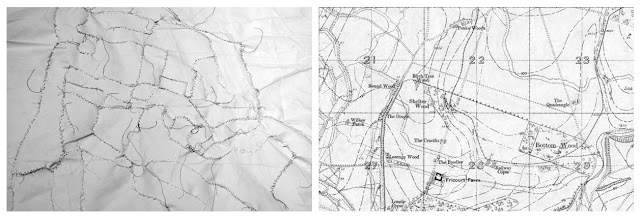

Having completed my last stitching project based on trench maps from World War I, I decided to try and superimpose some postcard portraits onto them, of soldiers headed for the Front. In the first (below) I used the photograph of a family which I ‘projected’ onto the map as shown hanging on a washing line.

What strikes me about this image as a whole, is the contrast between now and then as it exists in the contrast between the black and white of the photograph and the colour of the day. This colour, and the sense of the nowness of the present, helps strengthen my own empathetic feelings towards those long since lost – and all but forgotten – to history.

The fact the map hangs on a line like an item of washing, also reinforces the sense of domesticity which is a theme running through some of the postcard portraits, many of which were taken in the backyards of soldiers (or their parents), where evidence of the everydayness of domestic life is in abundance.

One such photograph shows a young couple who’ve recently been married. They stand, unsure of what the future brings, both wearing a look full of apprehension, staring into the lens of the camera, as if this ‘clock for seeing’ as Barthes once referred to them, really could show them the future.

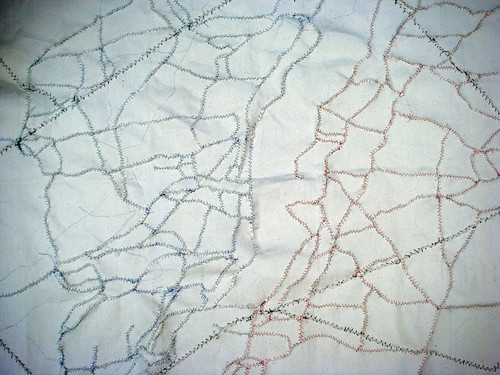

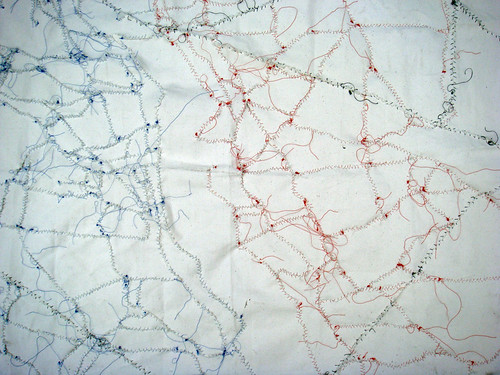

The image onto which their portrait has been projected shows the reverse side of the map, where the threads used to stitch the past together hang like the cut threads of countless lives.