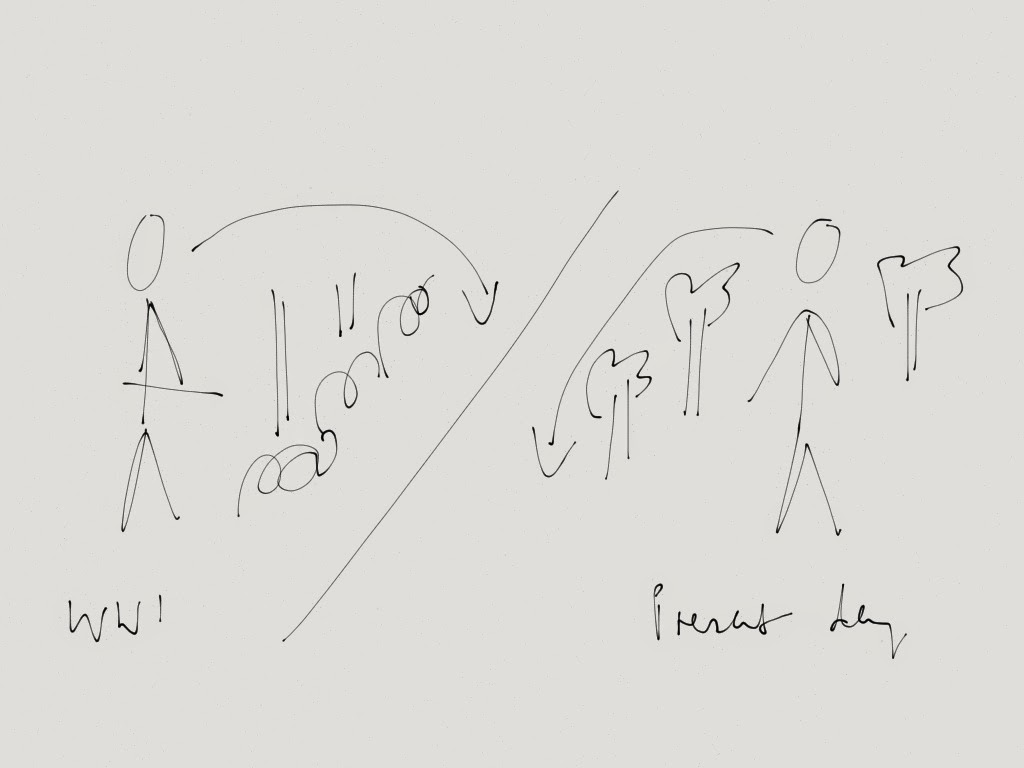

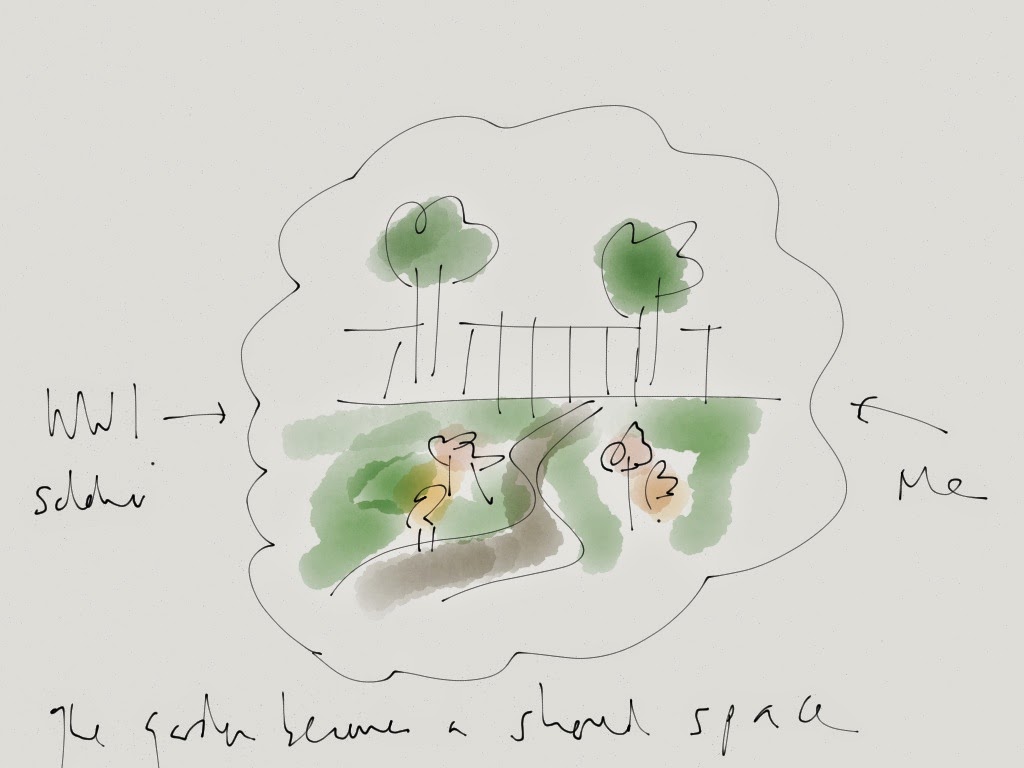

I was thinking about the post World War I landscape and how the years after 1918 saw a surge in spiritualism with grieving parents, wives and children seeking solace in the idea of their loved ones’ continued existence on ‘the other side’. There is, I think, a link with the Pastoral landscapes I’ve been thinking about of late, a place which seems best expressed by the poet Rilke:

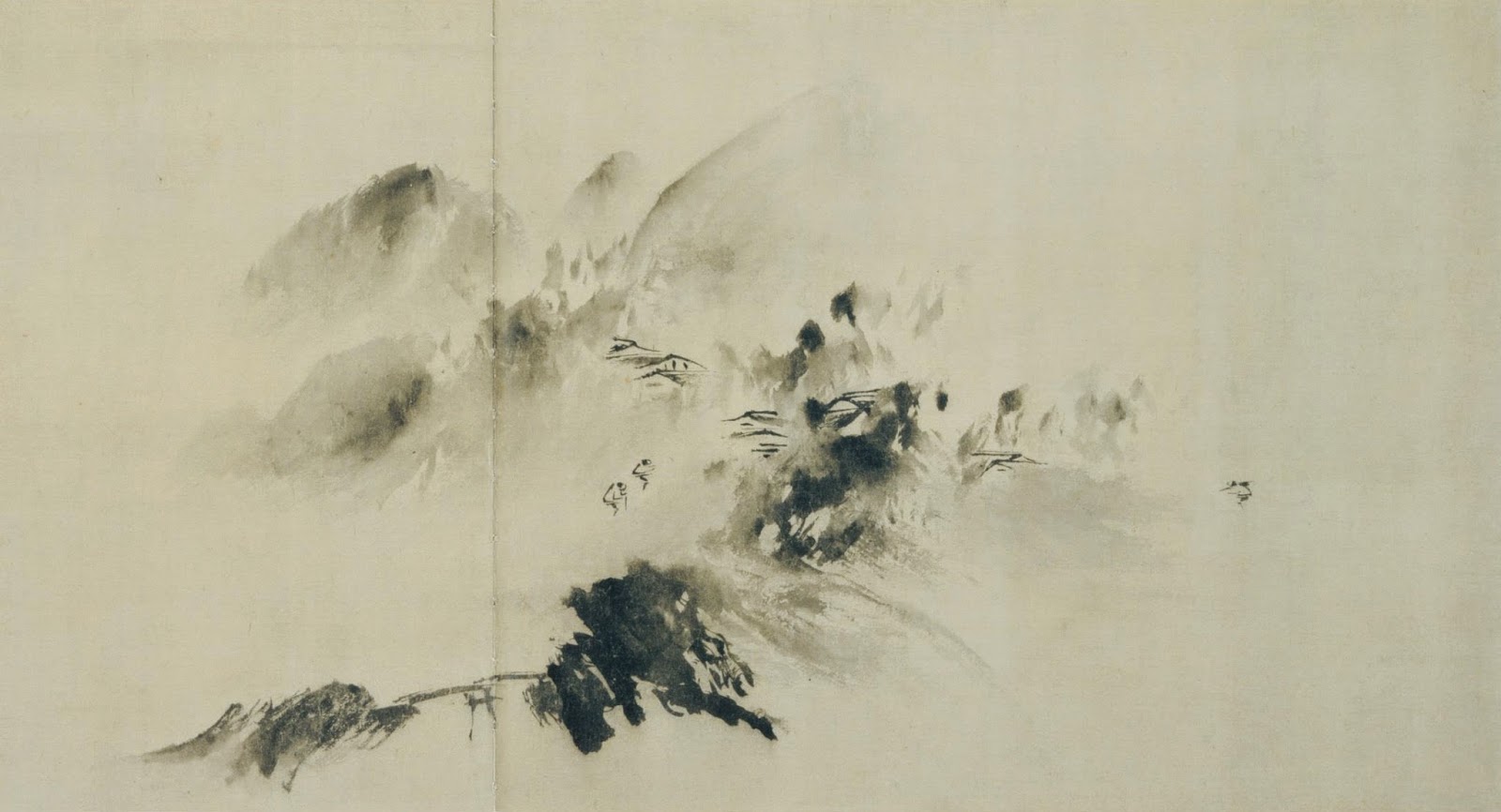

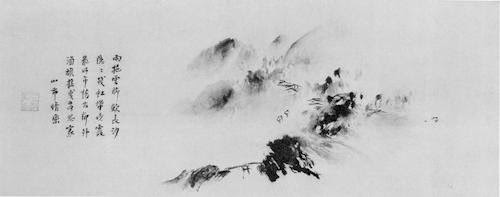

And gently she guides him through the vast Keening landscape, shows him temple columns, ruins of castles from which the Keening princes Once wisely governed the land. She shows him the towering trees of tears, the fields of melancholy in bloom (the living know this only in gentle leaf).

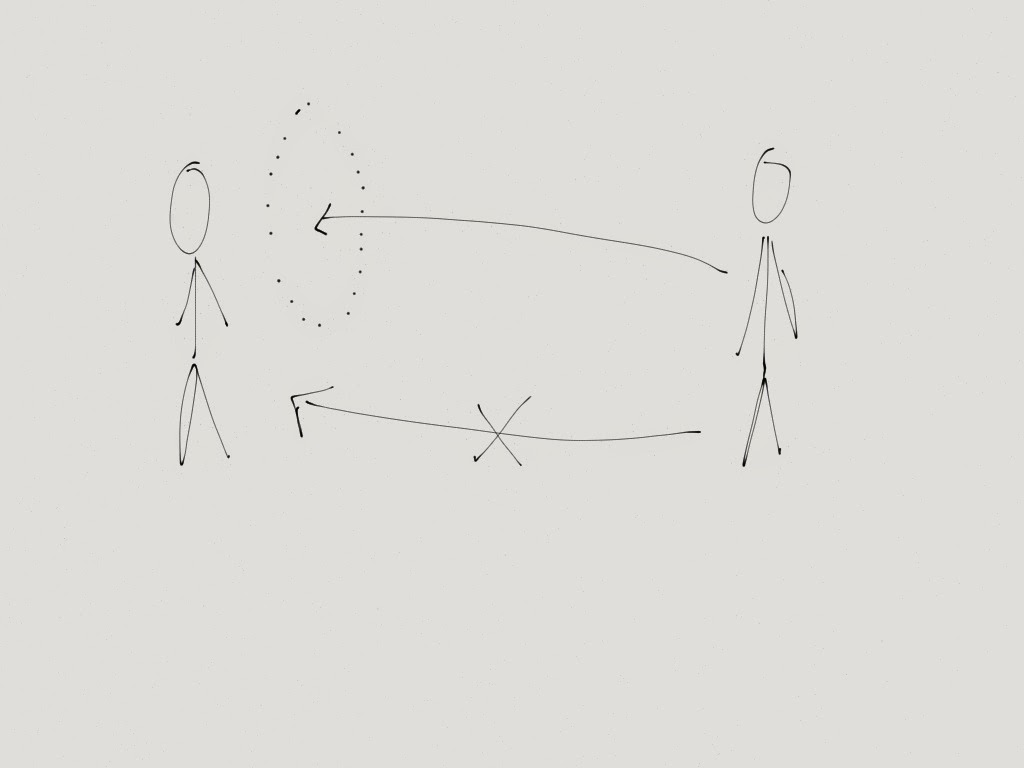

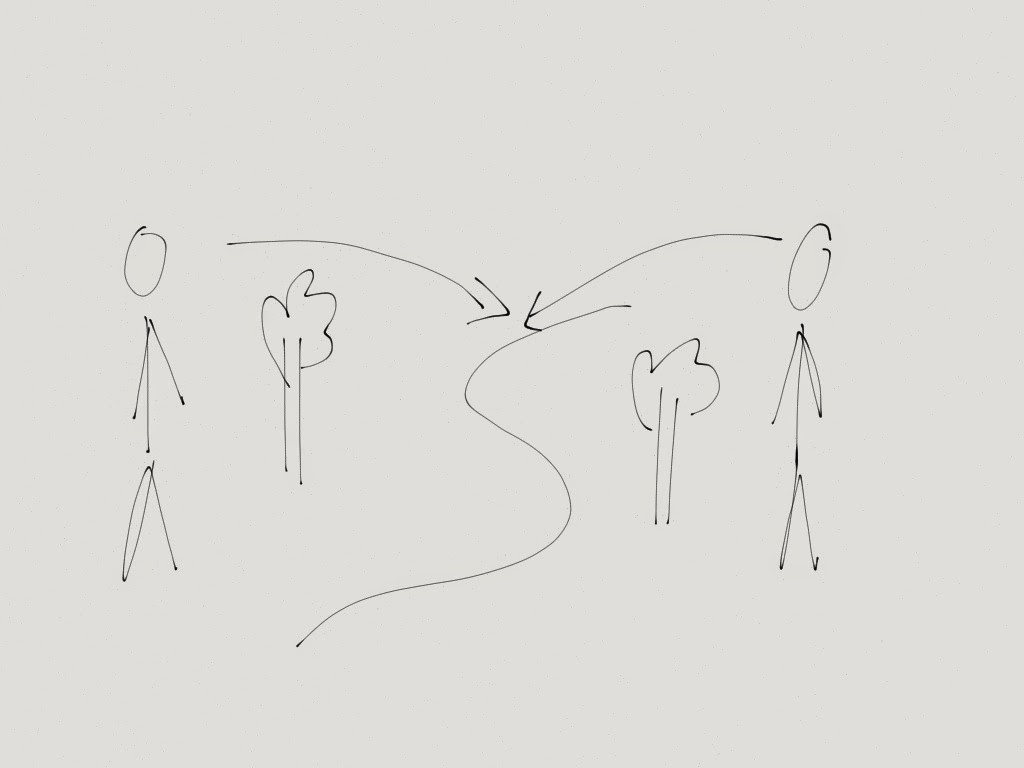

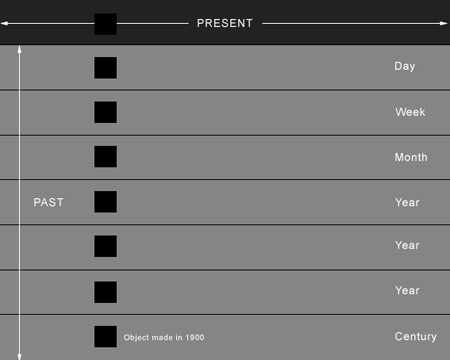

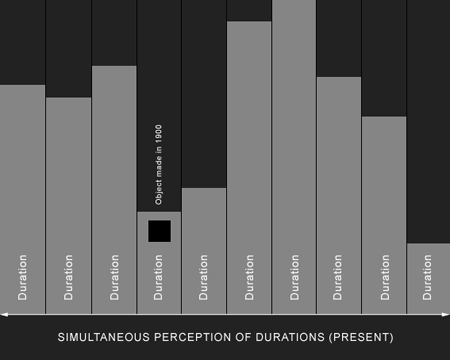

In tandem with this boom was the beginning of battlefield tours; tourists would visit the western front when the guns had hardly stopped firing. And I thought how interesting it was that there were these two different ways of looking for those who had gone: one, in a landscape of the imagination, the other, in the physical world; a pastoral plane and a place torn apart by war. And in many respects this reflects my work; the real world which we inhabit today and the plane of the past – a place in which we search for the dead in order that we might empathise with them.