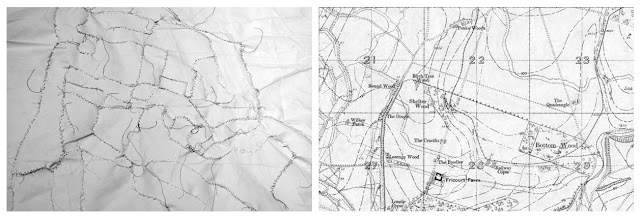

I’ve just completed – after several weeks of stitching – a piece of work called ‘Serre Palimpsest’ the creation of which I’ve been documenting on my blog. It became apparent soon after I started this work that this was a piece with two sides which may seem an obvious thing to say, but it seemed to me that the two sides we’re saying different things, just as things below the surface say something different to those above, whilst as the same time remaining connected.

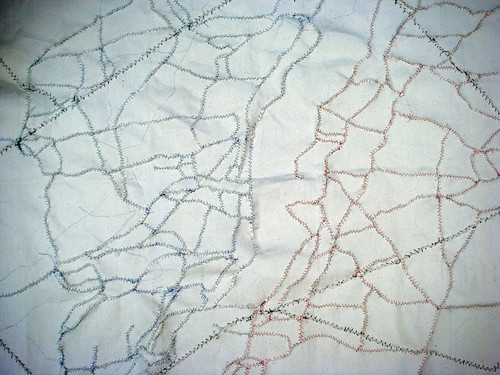

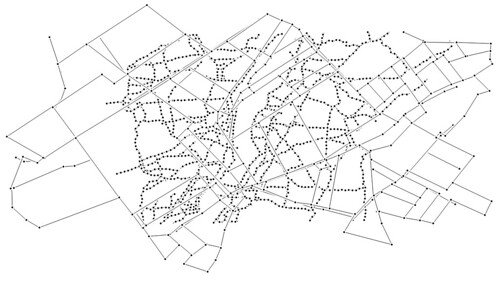

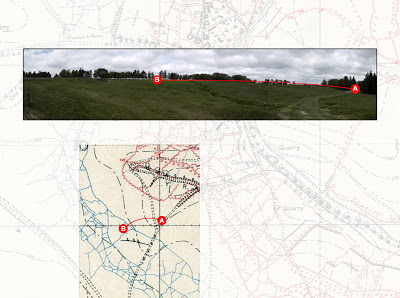

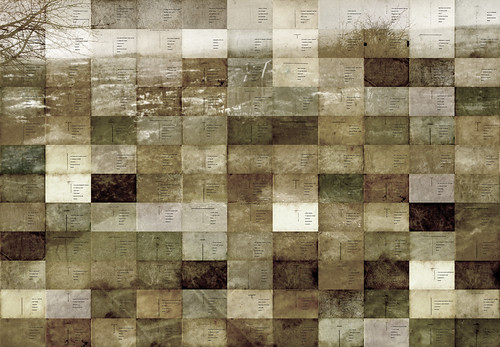

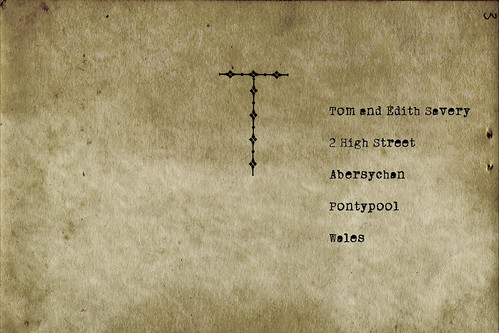

The two images below show the completed work. The first, the front:

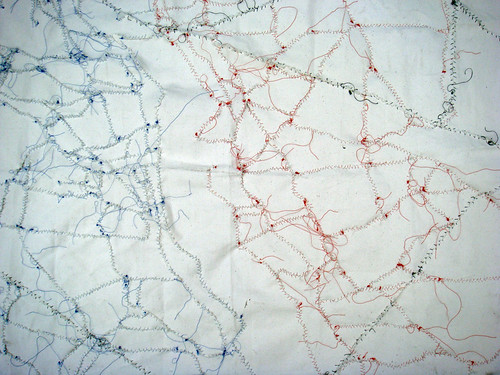

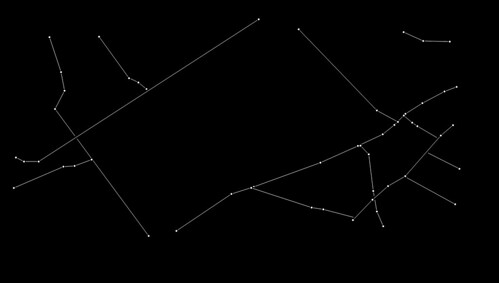

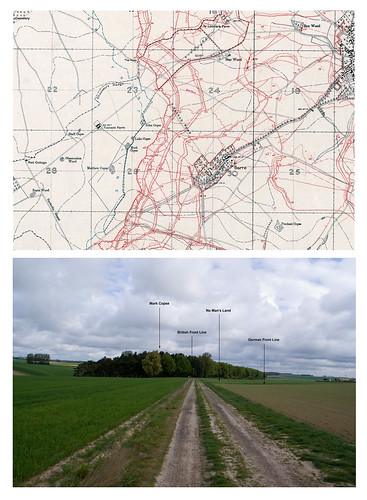

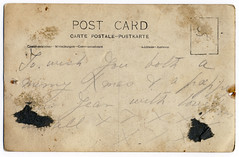

The second, the reverse:

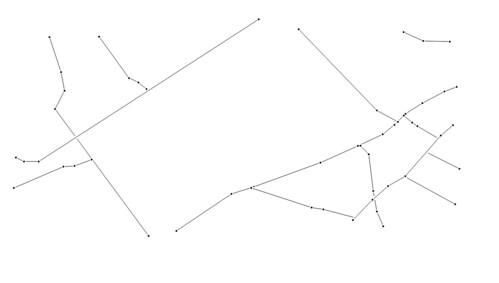

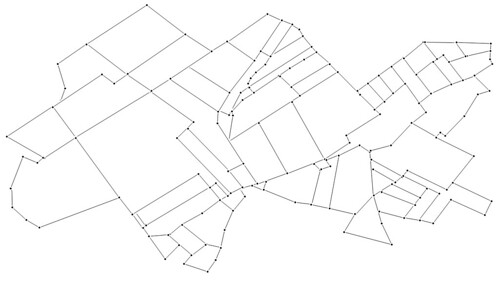

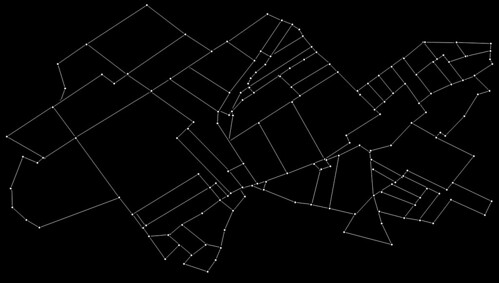

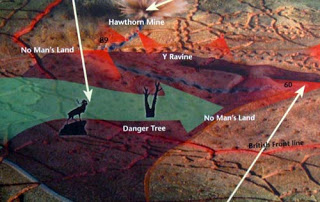

The lines stitched in black show the roads before the war (the modern day road system is pretty much the same), the blue stitching and red show the British and German trenches respectively – with No Man’s Land between, and the green stitching shows the modern day field boundaries.

What was interesting about creating the work was how the threads from the reverse of the piece would emerge into the front, mirroring the way pieces of the past (bits of old shell etc.) find their way to the surface after many years below the ground. The cut lines on the reverse made me think of the paths soldiers would have taken to get there; paths which in many cases were cut in the Somme.

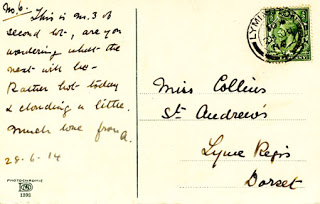

Occasionally, the threads would be tied together on the reverse which again made me think of how our lives today are similar to those who died in that their lives were lived lives too; of course their circumstances couldn’t have been more different, but the fact is that the vast statistics of the Somme comprise real individuals.

To take the photographs I hung the piece on the washing line. The weather was unseasonably hot and sunny, much like the weather would have been on the first day of the Battle of the Somme (1st July 1916). As I looked as the work swaying gently in the breeze, I thought about the photographs taken in the back gardens of those who were about to set off for the Front. I was reminded too of the backdrops used in studio-based photographs.