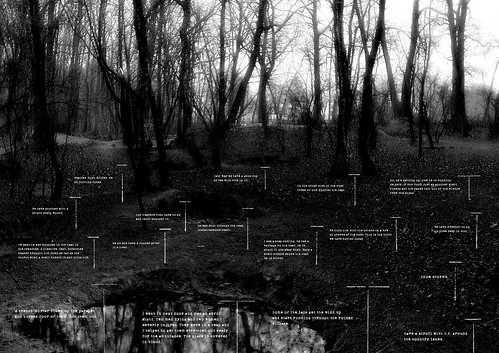

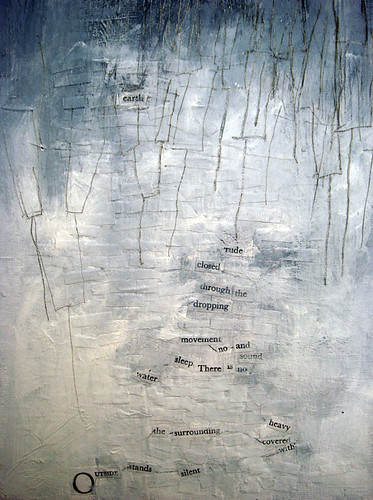

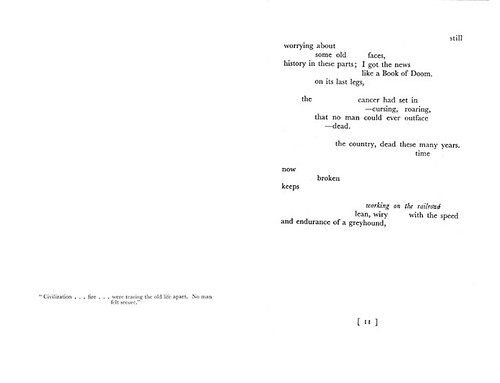

I worked again tonight on the studies for Heavy Water Sleep, working in landscape elements such as trees and sky. The original text from which the words are taken, ‘Pilgrims of the Wild’ by Grey Owl, is set chiefly in the forests of Canada. And in the ‘secondary text’ which inspired the work in the first place, ‘The Diaries of Adam Czerniakow’ there is a moving passage in which, following a visit outside the Warsaw Ghetto to the woods of Otwock, he writes simply, ‘… the air, the woods, breathing.’ Trees then seem integral to the work and have indeed been a recurring them in much of my work, particularly work to do with the Holocaust and World War I.

I wanted then to use trees in these works and found myself using a stylised form which I’d scribbled one day in my notebook based on lines you find in Family Tree diagrams.

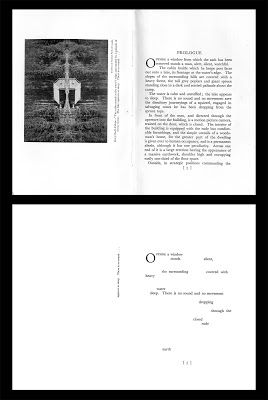

This symbolic tree was in part inspired by some work I did on the First World War in which I used the dividing lines on the backs of original wartime postcards to symbolise the bond between the anonymous individuals who died in the war and their families back at home. These ‘T’ shaped divides reminded me of photographs in which hastily dug graves were marked on battlefields with crude crucifixes. I therefore created landscapes (based on my visits to battlefield sites on what had been the Front) and used these T-shapes to represent graves.

From these T-shapes I derived the forms for the trees below.

The link between them and the Ts above is an obvious one – even more so when one considers the original inspiration for this work.

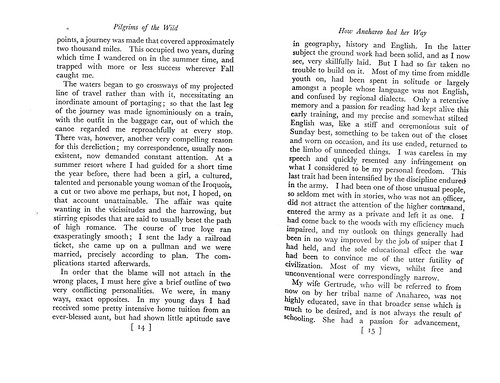

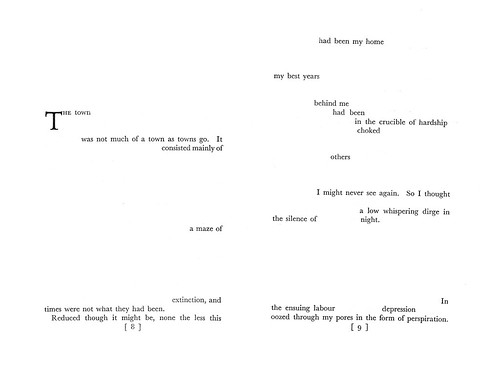

![14-15 [17.06.11]](https://farm4.static.flickr.com/3059/5841597001_471957f641.jpg)

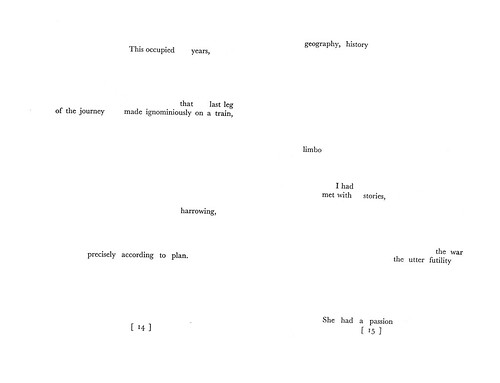

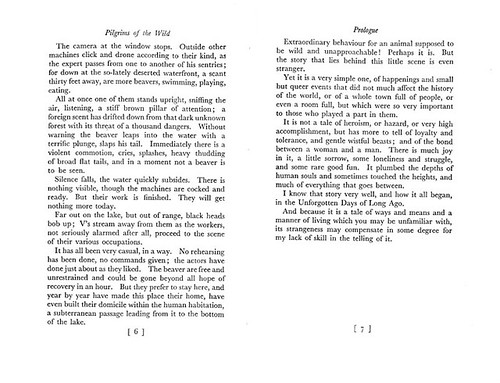

![08-09 [29-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5247/5303331149_0a89793a3e.jpg)

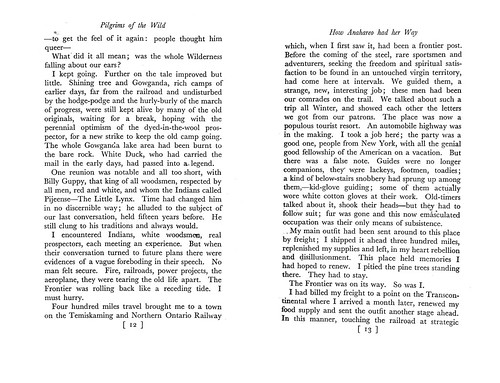

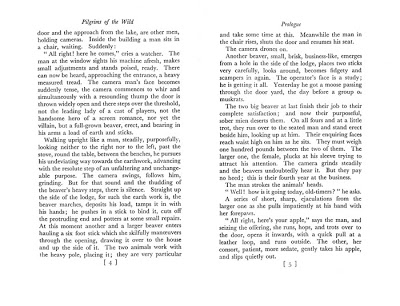

![06/07 - Version 2 [22-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5201/5283413870_e12da0c9dc.jpg)

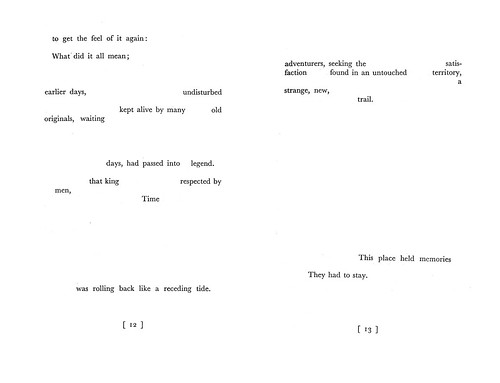

![06/07 - Version 2 [22-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5289/5282813285_dca9eda7f1.jpg)

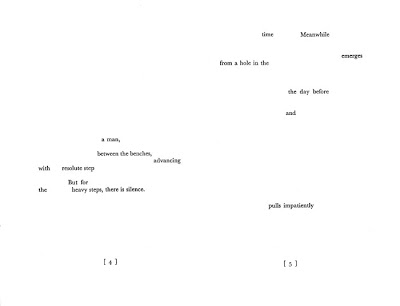

![04/05 - Version 2 [21-12-2010]](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5243/5280921725_3d72b17df6.jpg)