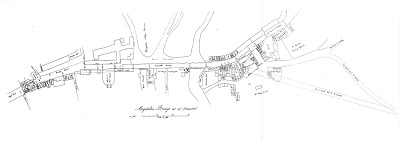

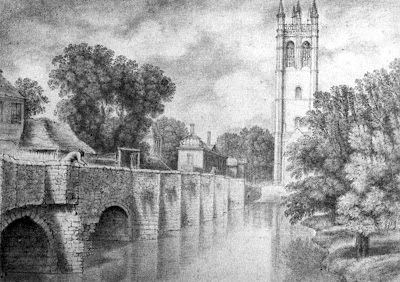

Whilst looking through some old research I did a few years ago, I came across the drawing reproduced below of Magdalen Bridge and its environs taken from John Gwynn’s survey of 1772.

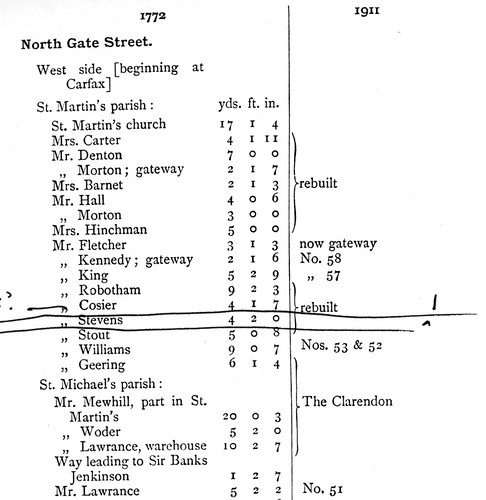

It shows the route we know the stranger took – the narrative line of this story – on December 12th 1770 along with the names of those who lived or owned properties bordering the street in 1771/72. Interestingly, my namesake – at least as far as my surname goes – owned property just in front of the old church of St. Clement which was demolished in 1828.