I’ve almost completed my map of observations made during a number of walks over the past few weeks and am now looking to see how I can progress this line of work.

The paper shown above has started to soften, from being carried for so long in my pocket and being held in my hand as I walk. It’s started to feel almost like material. I like the way too that it’s acquired those tell-take signs of wear and tear; dog-eared corners, rips and holes and creases.

On the reverse, you can see the selotape used to keep it all together, indeed there is something about this side which I really like.

I like the idea of these pieces becoming maps of individuals rather than just a place, while at the same time representing people as places – or at least the product of places. I like the idea of them becoming patterns, such as clothing patterns, again giving a sense of the individual.

Another part of this process has been the recording of my walks using GPS. I have, for this work, been putting them all together in one image.

In our minds, when we think about our own past journeys, there is little sense of space, i.e. the physical space between the places in which we made those journeys. Everything is heaped together. Time, like physical space is also similarly compressed. All the walks I’ve made for this work therefore are heaped one on top of the other, with little regard to their geography or temporality. The past with which I seek to identify is also like this. Geography and time are compressed. Everything is fragmentary.

In any given place – for example, Oxford – we can, as we walk down an ancient road, follow the (fragmentary) course of a life lived centuries ago. But walking down another road, we turn and pick up the fragment of another life. And so on and so on.

It is this fragmentary nature of past time, and its compression of time and space, which makes it sometimes hard of for us to empathise with anonymous individuals who lived in the distant past. To make sense of the fragments, we need to see them in the context of the present – in the nowness of the present. By doing this, we can begin to unpick these matted strands of time and space.

History is the attempt to make sense of the fragments left behind by time – to construct a narrative of events with a beginning and an end. It has a point A and a point B, between which the narrative weaves a path, much like a script, novel or score. What I’m interested in however are those fragments, not as parts of a narrative progression, but as fragments of a moment in time – a moment which was once now. As I’ve written before:

Access to the past therefore comes… through the careful observation of a part in which the whole can be observed. As Henri Bortoft writes in The Wholeness of Nature – Goethe’s Way of Seeing; ‘…thus the whole emerges simultaneously with the accumulation of the parts, not because it is the sum of the parts, but because it is immanent within them’.

Consider the span of an hour, and imagine a city over the course of that hour with everything that would happen throughout that period of time; history with its refined narrative thread, is rather like a line – a route – drawn through a map of that place. The line delineates space (in that it starts then ends elsewhere) but we know nothing of what happens around it – the mundane, everyday things which make the present – now – what it is. In my walks I capture moments, observations of mundane things happening around me as I walk.

For example:

A man talks holding his hat

A flag flies, fluttering in the growing wind

The next bus is due

A car beeps

Amber, red, the signal beeps

The brakes hiss on a bus

One could argue that these observations still represent a linear sequence rather than being fragments of a single moment in time. However, reading them, one does get a sense of the nowness of the past. The route as drawn by the GPS represents the narrative thread (history) whereas the text represents the individual moments from which the narrative is constructed.

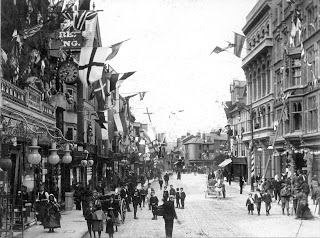

Imagine if someone had done the same in 1897 at the time of last Diamond Jubilee.

We get a sense of the nowness of a past time from images such as that above, but as Roland Bathes states, time in photographs is engorged. It doesn’t move. With the work I’ve made above however, the immediacy of a past time is captured, but, unlike photographs, is fluid. And it is this fluidity which is crucial to an empathetic engagement with the past. For the nowness of the present isn’t static, but rather flows within us and around us.

The following text from Robert Macfarlane’s ‘The Wild Places,’ interested me a great deal in light of what I’ve written:

“Much of what we know of the life of the monks of Enlli and places like it, is inferred from the rich literature which they left behind. Their poems speak eloquently of a passionate and precise relationship with nature, and of the blend of receptivity and detachment which characterised their interactions with it. Some of the poems read like jotted lists, or field-notes: ‘Swarms of bees, beetles, soft music of the world, a gentle humming; brent geese, barnacle geese, shortly before All Hallows, music of the dark wild torrent.'”