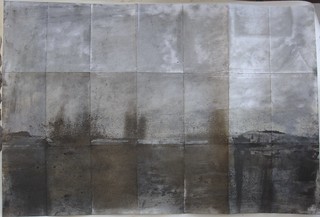

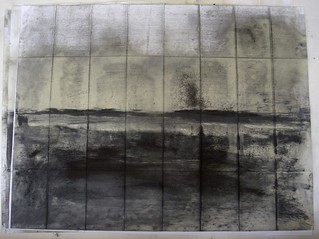

One of the nicest compliments I received during Friday’s private view was ‘…these remind me of Siegfried Sassoon…’. The works in question were those images of imagined World War I landscapes painted onto folded paper, one of which I have shown below:

In fact, the war poets were brought up a number of times in relation to these works which – for obvious reasons – pleased me enormously. But, I wondered what it was about these pieces which called to mind the poets?

One of the poets I’ve become increasingly interested in, is Edward Thomas – killed at the battle of Arras in 1917. I first became aware of his work whilst reading a book of World War I poetry, in which I found his poem ‘Roads’ (a poem I’ve already discussed in relation to my work). It was then in Robert Macfarlane’s book ‘Wild Places’ that I encountered Thomas again, this time in relation to another poet, Ivor Gurney. In a previous blog I wrote:

After returning from the war, Ivor Gurney, like so many others suffered a breakdown (he’d suffered his first in 1913) and a passage in Macfarlane’s book, which describes the visits to Gurney – within the Dartford asylum – by Helen Thomas, the widow of Edward Thomas is particularly moving. Helen took with her one of her husband’s Ordnance survey maps of Gloucestershire:

‘She recalled afterwards that Gurney, on being shown the map, took it at once from her, and spread it out on his bed, in his hot little white-tiled room in the asylum, with the sunlight falling in patterns upon the floor. Then the two of them kneeled together by the bed and traced out, with their fingers, walks that they and Edward had taken in the past.’

Macfarlane discusses Thomas in another book, ‘The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot,’ in which he writes how for Thomas, paths “connected real places but… also led outwards to metaphysics, backwards to history and inwards to the self. These traverses – between the conceptual, the spectral and the personal – occur often without signage in his writing, and are among its most characteristic events. He imagined himself in topographical terms. Corners, junctions, stiles, fingerposts, forks, crossroads, trivia, beckoning over-the-hill paths, tracks that led to danger, death or bliss: he internalized the features of path-filled landscapes such that they gave form to his melancholy and his hopes. Walking was a means of personal myth-making, but it also shaped his everyday longings: he not only thought on paths and of them, but also with them.”

Ever since I walked a path in Wales on which I knew my great-great grandfather walked every day to the mine in which he worked, I’ve been interested in the idea of people as place (and vice-versa) – see Landscape DNA – the simultaneity of stories so far. The path from the small town of Hafodyrynys to Llanhilleth where he worked, not only connected those two places, it also connected me with my ancestor. It did just what Thomas suggested; connected real places but also went backwards to the past and inwards to my own self. As Macfarlane puts it: “paths run through people as surely as they run through places.”

It was important for me that the images shown above did not appear so much as pictures – objects stuck on a wall – as objects of use. I wanted them to appear as if they’d been unfolded rather than simply painted, that like maps, they could be read rather than simply looked at. I wanted them to retain the potential for being folded (which, if they were framed, wouldn’t have been possible) for this inherent potential of folding and unfolding refers back to an observation I made whilst studying an old trench map.

During that observation I wrote, “…the past movements associated with this map are therefore recorded in its folds. It resists being folded any other way.”

The folds in the map are like ancient paths in a landscape. We can walk (within reason) wherever we like through a place, but more often than not, we will follow the way of countless others before us. Paths are themselves like folds within the landscape, and we, like the map, resist being folded any other way.

Macfarlane again writes how for Thomas “…map-reading approached mysticism: he described it as an ‘old power’, of which only a few people had the ‘glimmerings’.”

These glimmerings reminded me of a passage I read in Merlin Coverley’s book Psychogeography, in which he writes: “Certain shifting angles, certain receding perspectives, allow us to glimpse original conceptions of space, but this vision remains fragmentary…”

These ‘glimmerings’or ‘shifting angles’ are best seen or accessed through the everyday; observations of which I record in other map works.

This is something which Macfarlane again seems to allude to in ‘The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot’, when he writes: “The journeys told here take their bearings from the distant past, but also from the debris and phenomena of the present, for this is often a double insistence of old landscapes: that they be read in the then but felt in the now. The waymarkers of my walks were not only dolmens, tumuli and long barrows, but also last year’s ash-leaf frails (brittle in the hand), last night’s fox scat (rank in the nose), this minute’s bird call (sharp in the ear), the pylon’s lyric crackle and the crop-sprayer’s hiss.”

As I have recorded in my text-maps:

A man talks holding his hat

A flag flies, fluttering in the growing wind

The next bus is due

A car beeps

Amber, red, the signal beeps

The brakes hiss on a bus

Maps are objects which we fold and unfold. We unfold them to find our place within the landscape. We fold them and carry them with us. The process or unfolding and (en)folding: the idea that the past can be seen as being enfolded within the smallest objects and everyday observations in vital to my work; as is the way in which we are enfolded (written) into the landscape as we walk; the way in which the landscape is unfolded as we travel across it. Knowledge, likewise, is also unfolded in this way. As Tim Ingold writes in ‘Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description’:

“…knowledge is perpetually ‘under construction… the things of this world are their stories, identified not by fixed attributes but by their paths of movement in an unfolding [my italics] field of relations. Each is the focus of ongoing activity. Thus in the storied world… things do not exist, they occur. Where things meet, occurrences intertwine, as each becomes bound up in the other’s story. Every such binding is a place or topic. It is in this binding that knowledge is generated.”

Empathy is another important aspect of my work and I’ve stated before that empathy is an augmented discourse between bodily experience and knowledge. I like to think that with these works I’ve discovered a means of expressing that.

Finally, the works I’ve made are fragile pieces, and in another passage on Thomas, I found in Macfarlane’s prose a sentence which describes why they should be so: “His poems are thronged with ghosts, dark doubles, and deep forests in which paths peter out; his landscapes are often brittle surfaces, prone to sudden collapse.”

Perhaps this, in part, answers my question above.