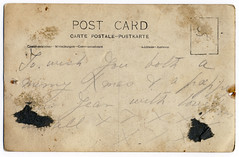

This evening I began working on an idea I’ve had for a while which incorporates the World War 1 postcards I was given by Tom Phillips. The idea was to show these postcards on a wall but with only a few the right way round i.e. showing the portrait (they are all portrait postcards of soldiers, most individual, some with other people). The rest would be displayed reversed showing either writing or, as is mostly the case, nothing – they would just be blank. I wasn’t sure how this would look and so I began putting the postcards up on my bedroom wall and fairly quickly I could see that the postcards, displayed in this way had an impact.

There was something about the blank postcards which was particularly resonant and the more I looked, the more I could see what it was that leant them this quality. On most of the blank postcards there is a motif running down the centre of the card (dividing the address from the text). These lines are of various designs, some very simple, others more elaborate. I decided to scan a few which can be found below.

For me these motifs have something of the grave about them, perhaps because they are each shaped a little like a crucifix, and they reminded me of some of the memorials I had seen in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

And as I started making connections, I thought of the X paintings and those I discussed in a previous entry – Black Mirrors and thought about how these marks could be incorporated into a work just like the symbol of the ‘X’.

I also thought how these various motifs/symbols resembled the botanic labels I’ve had made, each engraved with the name of one of my ancestors such as that of Henry Jones (below).

And finally, one last connection between the motifs and a work I made in November 2006, soon after a visit made to Auschwitz-Birkenau.