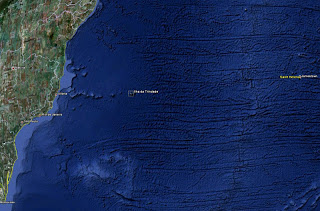

As part of my research during this residency, I’m undertaking a number of walks in and around Newcastle. During the walks, I write lists of observations; typically things which are seemingly insignificant or everday occurrences. Each walk is also recorded using GPS as are the number of steps using a pedometer.

The first two lists can be found via the links below: