I’ve been working on some designs for a new series of pieces exploring how we perceive the past. I have taken as my starting point the following text I wrote about my work in general:

My work is, in part, an attempt to know the past as a present-day, lived experience; to empathise with those who lived before me and see the natural world as they would have seen it, before so much was lost.

In 2018 I visited the Foundling Museum in London, established as The Foundling Hospital in 1739 to receive and care for abandoned children. It was an emotional experience, not least because of the scraps of fabric left by mothers with their babies; a means of identifying their child in the event they might reclaim them in the future. Amounting to over 5000 items, this sad catalogue is Britain’s largest collection of 18th century textiles.

When we attempt to engage with the past, often what is left – whether a name, a ruin, an object or story – is like those scraps of fabric, and the dress from which the fabric was cut, the world from which they’re estranged. In our mind’s eye, we can take the scrap and attempt to extend its pattern to form a view of the world long gone; the dress from which it was cut, the woman who wore it, the streets down which she walked. Whether a name, a ruin, an object or story, the process is the same; we take a fragment and, in our imaginations, extend it.

But in this endeavour we are always like a parent, claiming a child with a mismatched pattern, pointing out the parts that rhyme, aware of those which don’t.

I wanted to create a series of paintings exploring this idea. The paintings would be based on patterns contemporary with a specific time – in this case the mid to late 18th century. I imagined myself designing a pattern for a dress for one of my female ancestors and chose my 5x great-grandmother, Lydia Stevens (1734-1822) who lived, and died, in Oxford. Originally, I had thought of creating patterns from scratch, basing them on 18th century fabrics, but this didn’t really work. The point is, we base our ideas of what the past was like on extant things and it therefore followed that I should do the same.

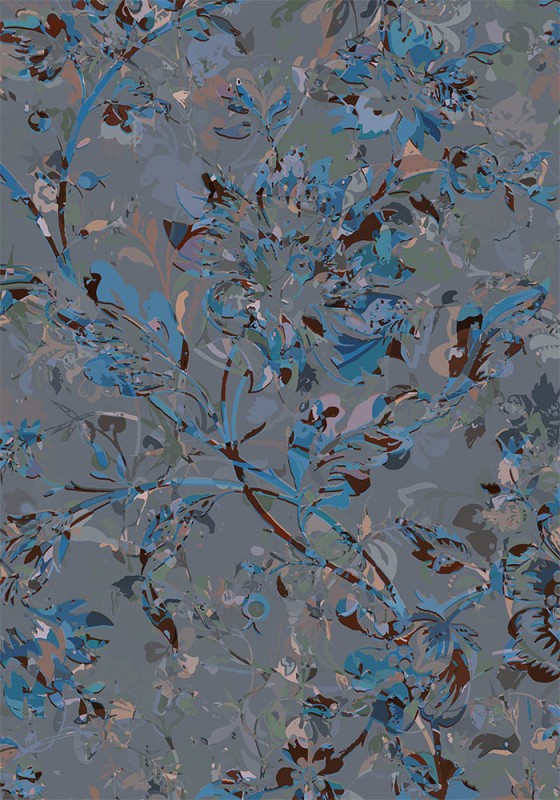

And so I chose a number of 18th century patterns which I layered in Adobe Illustrator, traced, divided and randomly coloured using colours (mostly!) in use at the time. I wanted to create works which alluded to fabrics of the 18th century but which looked different and which could, possibly, be viewed as landscapes in some way, whether images of a garden or wood.

The results were complex and yet they did exactly what I was hoping the would. They fragmented the original patterns to the point where the images combined to form a kind of kaleidoscopic image, one in which we might look and seek out a pattern, using our own experience to deduce what that pattern might have been. We might find a branch, a leaf or parts of a flower head and trace a path to find the rest, only to lose ourselves in yet more fragments.

So, the first group of images are as follows:

This last image is my preferred one. I like the colours and it has the feel of an 18th century fabric whilst at the same time retaining the sense of fragmentation I’ve aspired to. This line, from what I wrote above, is important:

But in this endeavour we are always like a parent, claiming a child with a mismatched pattern, pointing out the parts that rhyme, aware of those which don’t.

In this image we can see the traces of a coherent pattern or patterns; fragmentary ghosts of something that was once whole. We see a kaleidoscope of gestures and traces, which, every now and then cohere to form an image; a flower head, a leaf or a stalk. Our eye might trace the rhymes and search for the pattern, before losing the thread and finding only dissonance once again.

Of course, these are digital images. The question now is how to render these onto canvas, how do I translate these images into paint? Obviously it will be almost impossible to replicate them as paintings, but that is not a problem. In fact it is completely in keeping with the ideas behind the work.

These digital images, created from overlaid patterns from the 18th century, reflect the way we see the past; kaleidoscopic, unknowable, fragmentary. By working with fragments, by joining the dots in the vast and impossible network that made the past ‘now’, we might arrive at a flash of recognition. Such moments might arise in places which have changed little over time, or with objects still in situ like something dug from the ground. In those moments, something aligns between us in the present and people in the past, a kind of occultation which, for a second creates something new and fleeting; not the past and not the present; neither existence or non-existence, but something other. One thinks of Baily’s Beads, when, during a solar eclipse (such as I saw in 1999) the moon’s terrain lets slip the sunlight just before the total phase of the eclipse.

It’s not the moon, it’s not the sun. It’s something else. Something which exists for the briefest of moments. A flaring like the moment of recognition when two bodies, years apart, align and spark.

When I paint these images, I will I’m sure, find myself searching out the connections as I paint. The end results will be either one twist of the kaleidoscope or another; one which reveals a pattern or one which is simply fragments.