I have just finished reading two books; ‘Helgoland’ by Carlo Rovelli and, ‘Cracking the Walnut’ by Thich Nhat Hanh. It was in Helgoland, a book on Quantum Mechanics, that Rovelli mentioned the writings of an ancient, Indian Buddhist called Nāgārjuna which, he said, had had a profound effect on him. Having read some of Thich Nhat Hanh’s writing before, I found a commentary of his on the writing of Nāgārjuna which I subsequently bought.

As Rovelli writes:

“The central thesis of Nāgārjuna’s book is simply that there is nothing that exists in itself, independently from something else. The resonance with quantum mechanics is immediate. Obviously, Nāgārjuna knew nothing, and could not have imagined anything, about quanta – that is not the point. The point is that philosophers offer original ways of rethinking the world, and we can employ them if they turn out to be useful. The perspective offered by Nāgārjuna may perhaps make it a little easier to think about the quantum world.”

Signlessness is one of the three doors of liberation, along with with emptiness and aimlessness. I’d always found the idea of signlessness and emptiness rather sad, bordering on nihilistic, but reading ‘Cracking the Walnut’ I understood how I had been viewing these terms incorrectly. If we think of an object in and of itself as something which has ‘self-nature’ then we are not seeing that object (and thereby ourselves) as what they (and we) really are.

We are not things isolated from other things. We are things which manifest because of other things, which in turn manifest because of other things and so on. Objects (and again, ourselves) do not have a beginning and end as such (no-birth and no-death). But rather, when we die, we change. (This is not to say we reincarnate; we don’t die and become born again as another person or thing – that’s clearly nonsense.) ‘Cracking the Walnut’ goes deeply into the concepts of no-birth and no-death and ideas of dependent co-arising which is beyond the scope of both this blog and my current understanding, but the ideas of signlessess and emptiness are about this co-arising. We are not separate things (selfs) existing outside of other things, but changing manifestations of a connected world.

As Rovelli puts it:

“‘I’ is nothing other than the vast and interconnected set of phenomena that constitute it, each one dependent on something else.”

We are ’empty’ and ‘signless’ because we are not things in ourselves independent of other things.

It’s interesting that when I read Rovelli’s book and then words of Nāgārjuna (as explained by Thich Nhat Hanh), I realised that in some respects, I had been thinking along these lines in the way I perceive historical objects or places in my work, particularly when it came to the process of Goethean Observations.

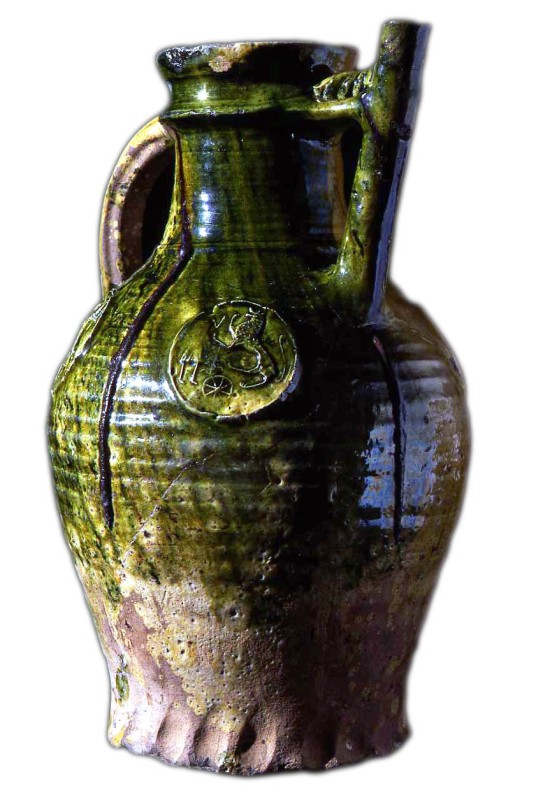

For example, a Roman bottle I bought.

One can look at it as what it appears to be; a glass bottle dating to the 3rd century CE. That is its ‘sign’. But when we look more closely, we can see that it’s so much more than ‘just’ an ancient bottle. It’s sand, heated then blown into the shape of the bottle. It’s the place from whence the sand came; it’s the sea and the long process of rock weathered down into grains. It’s weather, wind and waves. It is the breath of a man who lived nearly two millennia ago. It’s one of many moments in his life. It is his learning, his skill, his thoughts and mood that day. It’s the place in which it was kept; the oil it contained and the woman who rubbed the oil rub on their skin. It’s the grave in which they were laid with the bottle; the dark, the silence, the chemical process that caused its iridescence.

It is then, empty. Not because there is nothing in the bottle (there is, of course, air), but because it has no self-nature. It is not a thing independent of other things. It is, as Rovelli put it above, ‘nothing other than the vast and interconnected set of phenomena that constitute it, each one dependent on something else.’ The sea, the sand, the breath, the thoughts, the hands, the skin, the grave and so on. And, just as it is for the bottle, so it is with us.

In a recent blog post ‘Genius‘, I mentioned David Whyte’s book, ‘Consolations’ in which he writes:

‘Each one of us has a unique signature, inherited from our ancestors, our landscape, our language, and alongside it a half-hidden geology of our life as it has been lived: memories, hurts, triumphs and stories that have not yet been fully told. Each one of us is also a changing seasonal weather front, and what blows through us is made up not only of the gifts and heartbreaks of our own growing but also of our ancestors and the stories consciously and unconsciously passed to us about their lives.‘

In turn he describes the genius of landscape as being:

‘Genius is, by its original definition, something we already possess. Genius is best understood in its foundational and ancient sense, describing the specific underlying quality of a given place, as in the Latin genius loci, the spirit of a place; it describes a form of meeting, of air and land and trees, perhaps a hillside, a cliff edge, a flowing stream or a bridge across a river. It is the conversation of elements that makes a place incarnate, fully itself. It is the breeze on our skin, the particular freshness and odours of the water, or of the mountain or the sky in a given, actual geographical realm. You could go to many other places in the world with a cliff edge, a stream, a bridge, but it would not have the particular spirit or characteristic, the ambiance or the climate of this particular meeting place.

A place then is also empty. It is a ‘vast and interconnected set of phenomena‘.

Suddenly, more quotes began to come to mind; quotes I have used many times before; all of them seeming to concur with this way of thinking. I mentioned some in another blog post, ‘Knowing We Are There.’

One is a quote from American author and essayist Barry Lopez:

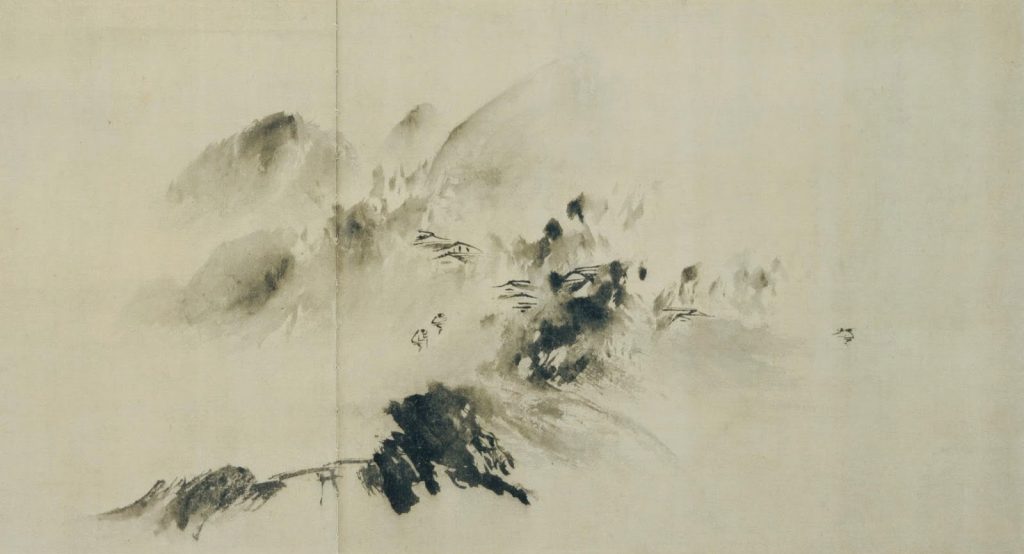

“One must wait for the moment when the thing — the hill, the tarn, the lunette, the kiss tank, the caliche flat, the bajada – ceases to be a thing and becomes something that knows we are there.”

Another by Christopher Tilley. In his book ‘The Materiality of Stone, Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology’, he writes:

“The trees ‘see’ the painter in a manner comparable to that in which the mirror ‘sees’ the painter: that is, the trees, like the mirror, let him become visible: they define a point of view on him which renders visible for him something that otherwise would remain invisible – his outside, his physiognomy, his carnal presence… The trees and mirror function as Other.”

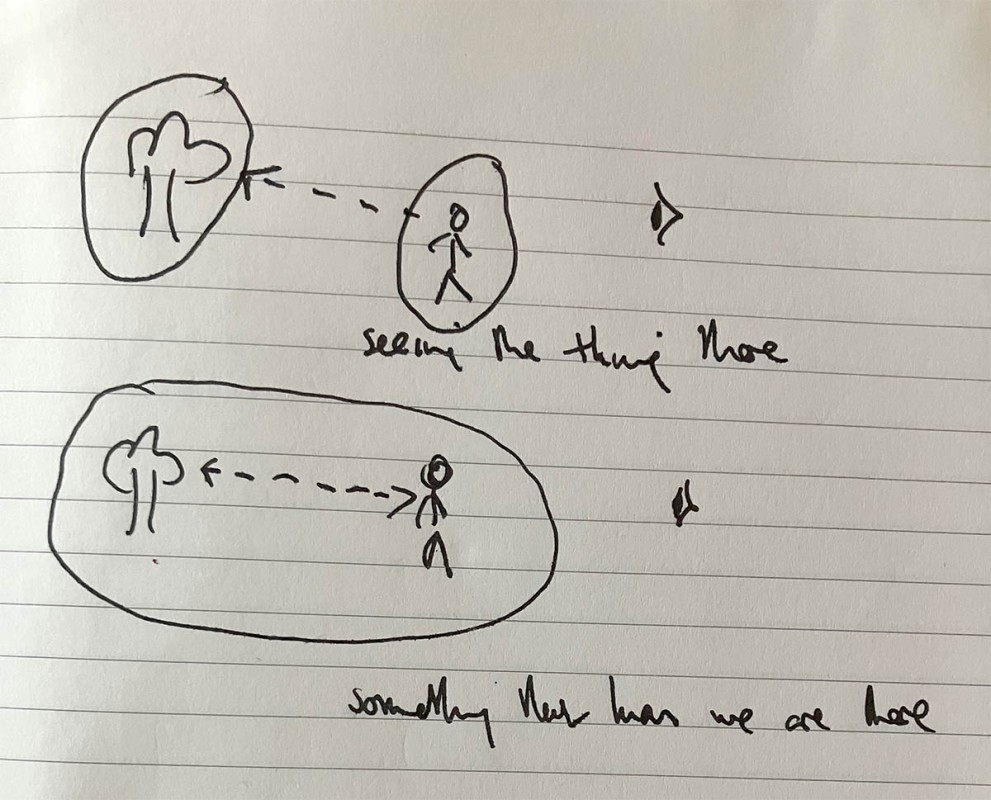

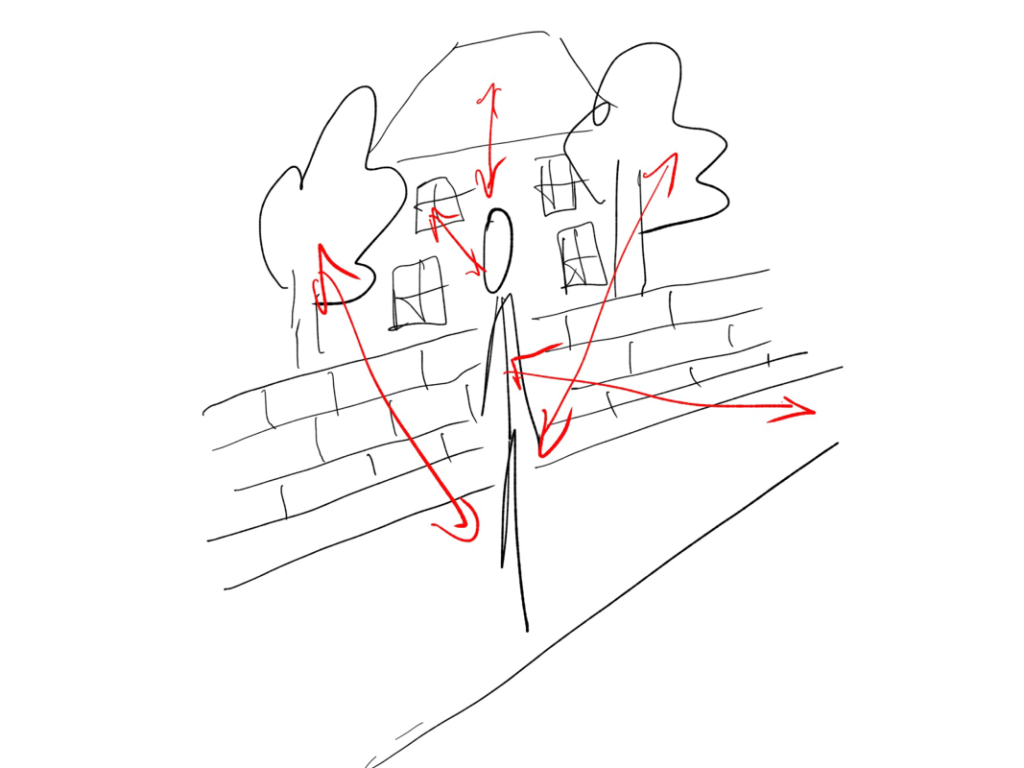

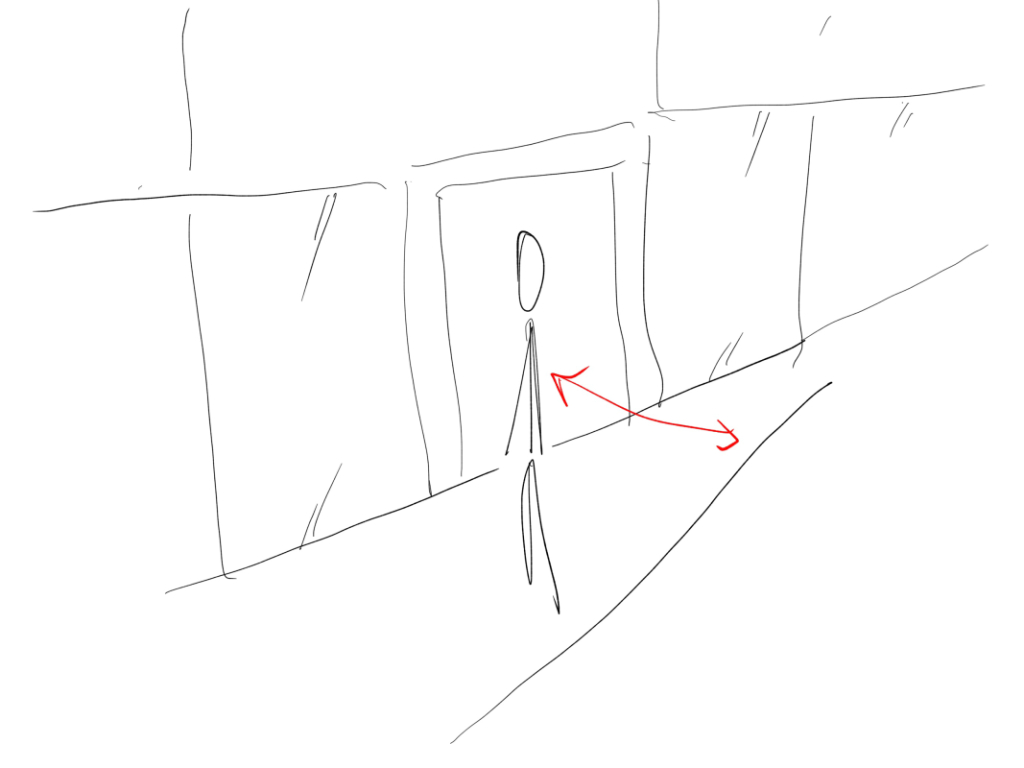

Interestingly, I drew a diagram to represent my thinking when I read Lopez’s quote, and now, over a year later, having read Rovelli’s work and the work of Nāgārjuna, it makes perfect sense.

There is not a tree and a person. There is interconnectedness.

But this interconnectedness isn’t confined to the present moment. In a post called ‘Measuring The Past‘, I wrote:

“To climb the peaks of our imagination and see a time long before we were born is, at the same time, to descend into the depths of our own non-existence, wherein which dark expanse, our imagination lights the dark as it does the paths that lead away from our deaths. Imagination and memory come together to blur the boundaries of our beginnings and ends, as if, like a book, the unseen words that might have been written before and after are suddenly revealed in all their infinite number.”

When we think about emptiness and the idea that we are that ‘vast and interconnected set of phenomena‘, we begin to see that that network isn’t confined to what we perceive as ‘now’, but rather a network which stretches back in time.

Whenever I’m in an art gallery looking at a painting, for example, one of JMW Turner’s, I often think of all the people that have stood where I am standing looking at that same painting. The painting might be hanging in a different place, but over time, thousands would have stood exactly where I am standing in relation to that same painting.

The painting is a node in a network linked to everyone who has ever stood and looked at it. I in turn am in that same network, linked to each of those people.

We can interpret Barry Lopez’s and Christopher Tilley’s quotes as revealing how it is not simply about us, as subjects, observing other objects. They too ‘observe’ us. That is, they manifest at that moment, because of us, because we are looking and vice-versa.

Before reading any of the above books I thought in this way whenever i thought about objects in museums. It’s how I can build the worlds to which those objects belonged, because essentially, it is the same world. There is only one of these vast, interconnected networks; one in which everything that exists and has ever existed is connected.

Thinking in this way, the glass bottle is a node in that network. However, like the painting, and like everyone who has ever looked at the bottle or the painting, we mustn’t think of the objects as something static (something with a self-nature) that stand like chess pieces on a board. Everything is in flux. The bottle is not a thing which came into existence fully formed in the 3rd century CE, just as the man who made it wasn’t born fully formed years before. They are both manifestations of other phenomena. The bottle is sand, fire and breath. It’s the sea and the waves, the pull of the moon; all things with which, in my own life, I’m familiar. If I think of the sea, I think of my holidays as a child. The sea and the sand become nodes linking me with the bottle, just as a breath links me with the man.

Then

Then Now

Now