When we look at a photograph, we are always outside the image, well beyond the scene that’s taking place. That might seem an obvious thing to say — especially if the photograph was taken long before we were born — but there are sometimes aspects of an image which plunge us deep into the ‘now of then’.

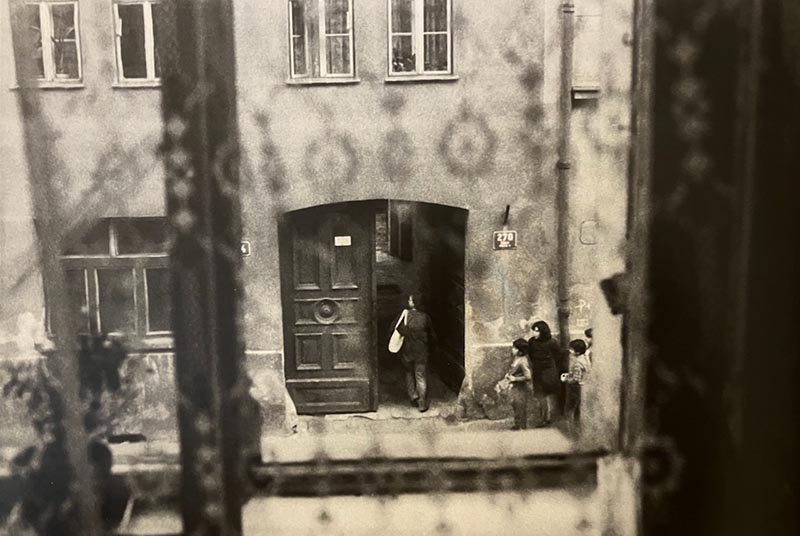

In this image — taken in May 1980 by a member of the then Czechoslovakian secret police — that thing is the net curtain, behind which the photographer — we — are standing. It is ironic, given that its purpose is to obscure rather than reveal, that the curtain serves to immerse us in the scene, extending the plane of the image back and behind us, combining the picture’s future and our past into one small room with a view.

We become the secret police, spying on — we can assume — the woman walking through the arch. But then, perhaps she’s not the target, but someone worthy of attention, captured with a click. We hear the click while scene is still playing, out and through the archway of the surveilled building, up and down the street and through the windows opposite.

Looking at the woman, her head is turned to the left. She is glancing down the street as she enters the block. The four children on the right of the image are also looking. What was that? What have they seen? I follow their gaze to the flowerpot just beyond the net curtain. I can’t lift the curtain lest I give myself away. But for a second I hold my breath and become aware of the noises around me.

I lean back, as if to avoid the possibility the woman might turn her head completely and glance up at the window, at that from behind which I’m looking 45 years in the future. I look away from her and ahead at the windows opposite. There are four of them, one open, the others closed, each dressed in the same net curtains. The sound — whatever it was, is — that happened down the street, has found its way through the open window, along with the children’s voices and the woman’s footsteps below. Is there someone there too, behind the curtain? A neighbour looking to see what the noise was, or another secret policeman following the same person. Perhaps it’s someone else, someone standing opposite, looking — like me — at a photograph somewhere in the future, one in which I’m looking back from behind a net curtain, there in the window across the street.

I look back at the woman, at her bag and wonder what’s inside.

In Camera Lucidea, Roland Bathes writes how “In the photograph, Time’s immobilisation assumes only an excessive, monstrous mode: Time is engorged…”

That’s certainly the case with this photograph. My mind becomes a conflation of the disinterested viewer — me — and the secret voyeur. What was that noise? What can they see? Who is the woman? What’s in her bag? Who’s she going to meet?

The questions pile up but they can never be answered. The photograph swells. It holds too much time. Something breaks.

And perhaps it’s that the children can hear?